Urgent message: Despite conventional wisdom, extensive research has shown that giving feedback at work—ostensibly to foster learning and improved performance—often has the opposite effect. The challenge for urgent care leaders, therefore, becomes learning to instead recognize excellent outcomes, and then nurture and reinforce the behaviors that led to them.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc is Chief Executive Officer of Velocity Urgent Care and is Practice Management Editor of The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine.

When it comes to the workplace, including urgent care organizations, we’re all pretty much married to the idea that in order to improve performance, we must give and receive feedback—whether it’s gentle, constructive, or even harsh. After all, this is the prevailing wisdom we’ve been taught for decades: when an activity, action, or task performed by another is considered subpar or falls short of some predefined standard, someone in a position of authority, experience, or expertise should rate their performance against that standard, and then explain how they can improve the next time around.

This method has long been thought to be the best way to promote learning and competency, as evidenced by bosses, managers, and leaders the world over leaning heavily on the doling out of frequent feedback as their preferred remediation tool.

This fidelity to the virtues of consistently giving and receiving feedback of course assumes that feedback is always appropriate and useful. However, a study of the neuroscience of feedback, as explored in a March-April 2019 Harvard Business Review (HBR) article, has turned this idea of “feedback always being useful” on its head: According to researchers, the giving of feedback that draws attention to, and focuses on, our shortcomings does not actually enable learning and improved performance. Rather, it impairs it to a significant degree.

To be clear, the researchers whose data are featured in the HBR article on the Fallacy of Feedback drew a marked distinction between the providing of necessary instruction and the subjective, opinion-based aspect of giving feedback. It is totally appropriate and necessary, for example, to provide a medical assistant in an urgent care setting instruction on the proper steps and protocols for performing some clinical task. If the MA forgets a step, or performs one of the protocols incorrectly, then of course it would be pointed out and explained properly. Feedback, however, as it was examined in the article, was about telling people your qualitative opinion of their performance, and how to perform it better. As the researchers in the article explained though, that sort of feedback fails to help people grow and thrive, and instead short-circuits their ability to learn.

Three Ill-Conceived Theories of Feedback

So why does feedback fail so miserably to produce its often well-meaning and intended effect? The researchers highlighted and summarized three inherent flaws that we as human beings bring to any subjective, feedback-giving process—yet accept as unassailable truths:

- The Theory of the Source of Truth. This theory asserts that we as individuals have an inherent blind spot for seeing our own weaknesses and shortcomings, and therefore must rely on our colleagues to observe them and point them out to us. The front desk receptionist does not realize she could be performing the patient check-in workflow more efficiently, or the MA is unaware that his triage routine isn’t optimal, for example. We take it as our duty to draw attention to what we perceive as their shortcomings and offer our subjective opinion on how they might improve.

- The Theory of Learning. This theory, as described by the researchers, hinges on the belief that learning is like “filling up an empty vessel.” In other words, your colleagues may feel that there are specific abilities you need to have to succeed, and if they don’t teach them to you through feedback, you’ll never acquire them. If you’ve never worked in patient care, the thinking goes, then the only way you can ever learn to create comfort and rapport with patients is if we show you how we go about it. Or, how can you quickly and efficiently inventory medical supplies without being given feedback on how we’ve always done it?

- The Theory of Excellence. This theory is based on the belief that the concept of excellence is “universal, analyzable, and describable,” and can be taught to and replicated in any individual once it has been clearly defined. The idea is, through feedback, we demonstrate to you what excellence is and where you’re falling short, and advise you on how to correct your shortcomings so that you, too, can achieve excellence. The care team at the crosstown urgent care center, for instance, consistently hits their target key performance indicators; therefore, they embody the excellence that your team must be lacking since you’re not achieving the same numbers.

As a result of our misguided allegiance to these three theories, we march forward in giving out corrective feedback that is often interpreted by the receiver as negative. And when we receive critical feedback or criticism, scientists show it activates the sympathetic nervous system, which triggers the well-known “flight or fight” response. In this state, all our mental and emotional energy is focused toward responding to the “threat “which, according to the researchers, “inhibits access to existing neural circuits and invokes cognitive, emotional, and perceptual impairment.” So we don’t fully hear and absorb the feedback we’re being given, and we fail to adapt and learn.

Excellence Is Idiosyncratic

In sum, the HBR article goes on to lay out what the researchers proved rather conclusively: None of the three widely held feedback theories are actually true; in fact, for the most part, they’re counterproductive.

The Source of Truth theory falls flat because, as it turns out, we humans are notoriously subjective when we attempt to rate someone. That is, our ratings of other people are always skewed toward our own idiosyncrasies and unconscious biases. Meaning, our ratings reflect more on ourselves than the people we’re attempting to rate.

The Theory of Learning is misguided because, as the researchers show, we learn not from a completely blank slate, but by “adding to, reinforcing, and refining” the knowledge and skills that we already possess. True learning piggybacks and branches off our pre-existing competencies and strengths.

Finally, the Theory of Excellence—which relates to something we’re all after in our performances—is idiosyncratic, specific to each individual, and not a static concept that can be easily transferred between people with varying talents, personalities, and learning styles. Excellence is not something you teach; it flows naturally and effortlessly through each individual, but only when it’s nurtured and cultivated.

Reinforce Excellent Outcomes

True learning occurs only when we understand how to improve by adding nuance to our base knowledge, experience, and skills. And it’s dependent not on someone else’s biased opinion or criticism, but of our own understanding of where we’re already thriving and excelling. The key to getting people to grow and excel, according to the HBR article, is actively looking for excellent outcomes, and then drawing attention to them to help the individual recognize what they just did. When you witness an employee perform in a way that positively resonated with you, for example, you should stop what you’re doing and highlight it for them. Ask questions on what they were thinking and express how witnessing their excellent outcome made you feel. This allows the employee to gain an insight and recognize a pattern that they can then anchor, fine-tune, and duplicate going forward.

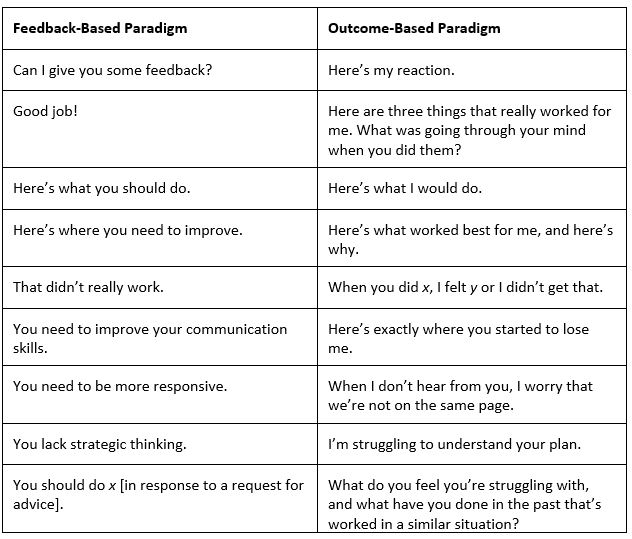

This, of course, will mean discarding the old feedback/criticism model forever and shifting to a new organizational paradigm—a learning culture where the focus is not on negative feedback and criticism, but one of “teachable moments.” It becomes more about calling attention to strengths rather than weaknesses. In general, it’s about keeping a positive, uplifting culture focused on continual improvement where team members are humble enough to admit mistakes and innovative enough to come up with new ways of doing things when the old ways no longer produce desired outcomes. To that end, the following table, adapted from the HBR article, provides several excellent examples of positive, noncritical word phrasing you can use in place of some of the old, habitual refrains:

Conclusion

Teaching and instruction will always be necessary in any work environment, with urgent care being no exception. It’s the overreliance on biased, subjective, error-laden, and emotionally taxing feedback, however, that hinders growth, learning, innovation, and excellence. To help your staff truly excel and thrive, you must make it a priority to instead draw attention to the actions and behaviors that resulted in excellent outcomes so they can further build upon their inherent strengths while gaining valuable insights into their own personal version of excellence. This is truly the path forward to building excellent teams who enjoy the freedom and encouragement to discover and perform as their best selves in the workplace.