Urgent message: Clinicians must be able to determine the cause and severity of injury in patients with neck pain, especially in the very young, whose symptoms vary according to their developmental status, and in the elderly, who have weaker bones and degenerative changes.

Introduction

Avariety of patients from children to the elderly will present to an urgent care Center with the chief symptom of neck pain. Cervical spine (C-spine) injuries occur in 3.7% of adults who sustain blunt trauma and present to an emergency department (ED), and almost half of those are unstable injuries, which if not diagnosed and treated can result in spinal cord injury.1 For urgent care clinicians, these are some of the issues at hand to consider:

- Who needs C-spine imaging?

- Is an x-ray sufficient?

- Who needs transfer to a hospital for further trauma

- evaluation?

Medical History

The mechanism of injury helps determine whether the patient is at minimal or high risk for significant injuries and provides clues in the identification of more specific injury patterns. Determining the location and duration of pain, exacerbating factors, relieving factors, time of onset, and associated symptoms helps the clinician determine a differential diagnosis. Characterizing the pain can be helpful when considering the specific organ systems involved—for example, pain that shoots down the arm is associated with a neurologic injury until proven otherwise.

Physical Examination

Initially, assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation should be performed. This can usually be done within seconds in a patient who is ambulatory and who responds verbally. A complete neurologic examination, including assessment of the pupils, sensation, strength, and cerebellum, is needed because neck injuries are often associated with neurologic injuries.

Focusing on the neck, determine the location of neck tenderness. During the musculoskeletal examination, palpate from the occiput down the midline of the C-spine, checking for any midline tenderness. Is the pain localized to the bony C-spine or instead to the musculature? If there is no midline tenderness while the patient is at rest, have the patient flex, extend, and bend their neck to the side. Check for any midline tenderness while testing the cervical spine range of motion. Is the pain worse with movement? Are there neurologic symptoms when the patient is at rest or moves through the range of motion? Because the cervical nerves innervate the muscles of the upper extremities, the focused physical examination includes taking the upper extremities through their full range of motion.

Patients with significant midline C-spine tenderness or focal neurologic deficits should be placed in a cervical collar and transported to an ED for advanced imaging.

Testing

To guide the examination and to determine the need for imaging, two clinical rules have been validated: the NEXUS Low-Risk Criteria2 and the Canadian C-Spine Rule. The NEXUS criteria were developed to reduce the need for C-spine imaging. As research continued, the Canadian C-Spine rule was developed with a similar focus: to clear C-spines without radiographs and at the same time recognize clinically significant injuries.

The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) was a multicenter, prospective, observational study of ED patients in multiple hospitals concerning the presence or absence of clinical criteria in those for whom C-spine imaging was ordered. The clinical criteria of NEXUS includes these items3:

- No neurologic abnormalities; the level of alertness is normal and there are no focal deficits

- No evidence of intoxication

- No posterior midline C-spine tenderness

- No other distracting painful injuries. Distracting injuries include long bone fractures, visceral injuries requiring surgical consultation, large lacerations, degloving injuries, crush injuries, large burns, or any injury producing acute functional impairment. If the patient cannot focus on the C-spine assessment because of other injuries, then the patient would be considered to have a distracting injury.

If a patient meets the NEXUS criteria, there is a 99.8% negative predictive value for C-spine injury, with a sensitivity of 99% and specificity of 12.9%.2

The Canadian C-Spine Rule goes through a flowchart of questions to determine the need for imaging. First, the clinician determines whether the patient has high risk factors that mandate radiologic studies4:

- Age ≥65 years

- Dangerous mechanism of injury, including

- A fall of >1 m or 5 stairs

- Axial load to the head, as in diving

- A high-speed MVA of >100 km/h

- An accident with a motor vehicle, or a bicycle collision

- Paresthesias in the extremities

If the patient has none of these high risks, the clinician can evaluate whether the patient has any lower risks that allow safe range-of-motion testing: involvement in a simple rear-end motor vehicle collision, ability to sit upright in the urgent care center, ability to be ambulatory at any time, delayed onset of neck pain, and absence of midline c-spine tenderness. If patients do not have any of these low-risk findings, they can undergo imaging. However, if they are examined and show that they can actively rotate their neck 45° to the left and right, imaging is not required.4

When to Obtain C-Spine Images

A patient with neck pain who has the following characteristics can be discharged from the urgent care center with medications for pain control and instructions to obtain follow-up care5:

- Can be cleared by the NEXUS criteria or the Canadian C-spine Rule

- Is an adult between the ages of 18 and 65 years

- Has normal findings on a neurologic examination

- Has no neck pain or tenderness with movement through the full range of motion

Alert patients with distracting injuries, neurologic deficits, and neck pain or tenderness on full range of motion need imaging. Although the course for Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) discusses plain films, it is not clear what the current role is for plain films in traumatic injuries of the neck. The EAST Practice Management Guidelines (from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma) recommend the use of computed tomography scans, given the potential for missed injury on plain films.5

If the mechanism of injury involved a low level of force and there is only a low suspicion that there is an unstable injury, clinical judgment can guide a decision about the need for imaging and the type of imaging. Consider obtaining plain films initially to assess alignment, for fractures, and for soft-tissue swelling. However, plain films cannot definitively exclude a fracture and do not allow assessment for spinal cord injury.

Interpreting Plain Film Cervical Spine Images

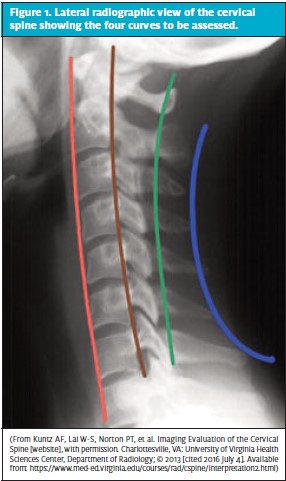

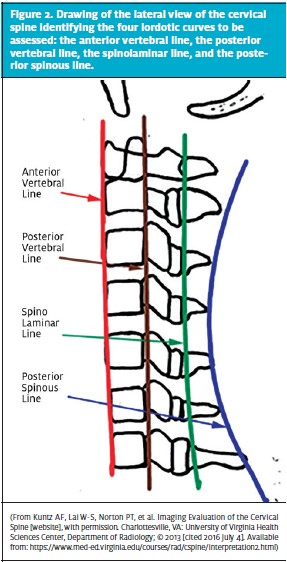

Three views are obtained in the trauma C-spine series: cross-table lateral, odontoid, and anteroposterior views. On the anteroposterior view, a straight line should connect the spinous processes. If the line is not straight, the clinician must consider the possibility of a unilateral facet dislocation. The lateral view has the most information. An adequate lateral film is essential for finding injury and includes the area from the base of the skull to T1.6 The alignment of the C-spine is assessed by reviewing the smooth lordotic curves of the anterior vertebral line, posterior vertebral line, spinolaminar line, and spinous process line (Figures 1 and 2).

Next, the clinician reviews the vertebral bodies for fractures or changes in bone density. Both the vertebral bodies and the intervertebral discs should be of uniform height.6 For example, if the anterior height of a vertebral body is ≥3 mm less than the posterior height, this should raise suspicion that there is a wedge compression fracture. On the lateral view, measure the predental space (distance between the anterior aspect of the odontoid and the posterior aspect of the anterior arch of C1), which should be no more than 3 mm in an adult and 5 mm in a child. To check the extra-axial soft tissues, measure the prevertebral space, which should be <7 mm at C2 and <22 mm at C6. If widening is noted, consider the presence of a hematoma in the area secondary to a fracture. Finally, assess the odontoid view. Lateral masses must be checked for symmetry,6 and the dens should be checked for integrity.

Patients with abnormalities noted on x-rays should be transferred to an ED for advanced imaging and reevaluation. Plain radiographs alone should not be used in patients at high risk (e.g., those who are ≥65 years of age, have severe arthritis, have osteoporosis).2

Urgent Care Evaluation of Geriatric Patients

Elderly patients with negative findings for the NEXUS criteria are a high-risk group for C-spine injuries, given their weaker bones and degenerative changes. In the FINE study, it was determined that the NEXUS criteria were not a valid tool for patients older than 65 years of age who presented after a fall from standing. Although ground-level falls are a low-energy mechanism of injury, they can be produce injury patterns in elderly patients that are typically found in high-energy, high-impact trauma. In the FINE study, researchers found that using the NEXUS criteria in patients older than 65 years of age would have meant missing 4.1% of clinically significant C-spine injuries and wrongly avoiding imaging in 29% of patients,7 which is a reminder to clinicians to maintain vigilance and consider advanced imaging in elderly patients presenting with neck pain secondary to trauma.

Urgent Care Evaluation of Pediatric Patients

Pediatric patients present with different injury patterns, given their various stages of development, and these differences must be considered when applying clinical decision rules to children. In 2001, a prospective study evaluated the application of the NEXUS criteria to pediatric patients who had sustained blunt trauma. All of those with C-spine injuries had positive findings for one or more NEXUS criteria.8 The NEXUS criteria can most likely be used in pediatric patients; however, given the low number of patients in the study and the minimal number of infants and young children enrolled, caution must be used especially in younger children, because the NEXUS criteria are not officially validated for children.

Four independent risk factors for C-spine injury have been identified for younger children9:

- Having a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of <14

- Having a GCS eye score of 1

- Having been in an MVA

- Being ≥2 years of age

These risk factors were scored on the basis of a retrospective study reviewing trauma in children. Three points were given for a GCS score of <14, 2 points for a GCS eye score of 1, 2 points for having been in an MVA, and 1 point for 2 years and older. A total score of <2 had a 99.9% negative predictive value in ruling out C-spine injury without radiographic imaging.9

Through retrospective research, clinicians found that pediatric patients at high risk present with abnormal findings on neurologic examinations, decreased mental status, neck pain, or torticollis, and thus they recommend imaging for these patients.10 In children not considered to be at high risk, examination is easily done in the urgent care setting. Clinicians examine them for C-spine tenderness in conjunction with the NEXUS criteria. Observe nonverbal children for normal neck range of motion. If they are moving their neck without discomfort and have full range of motion, C-spine imaging is not needed.10 If they do not move their neck or if they have severe discomfort when moving through the range of motion, place them in a pediatric cervical collar and pursue radiographic studies.

Conclusion

C-spine evaluation is critical in order to diagnose unstable injuries. Begin the evaluation with the NEXUS criteria or the Canadian C-Spine Rule, and when imaging is necessary, use clinical judgment to determine the need for transfer to a hospital versus radiographic studies in the urgent care setting. As with other disease processes, special consideration for geriatric and pediatric patients is crucial, given the lack of randomized control trials and the potential for significant injuries even with minor mechanisms of injury in geriatric patients. When the mechanism of injury is concerning, when there is decreased ability to obtain an adequate medical history and conduct a thorough physical examination, or when patients are from populations at greater risk for significant injury, remain alert for the need to transfer patients with neck injuries to an ED.

Citation: Maccagnano J. Urgent evaluation of traumatic neck pain. J Urgent Care Med. December 2016. Available at: https://www.jucm.com/urgent-evaluation-traumatic-neck-pain/.

References

- Pekmezci M, Theologis AA, Dionisio R, et al. Cervical spine clearance protocols in Level I, II, and III trauma centers in California. Spine J. 2015;15:398–404.

- Kanwar R, Delasobera BE, Hudson K, Frohna W. Emergency department evaluation and treatment of cervical spine injuries. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2015;33: 241–282.

- Hoffman JR, Wolfson AB, Todd K, Mower WR. Selective cervical spine radiography in blunt trauma: methodology of the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS). Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:461–469.

- Como JJ, Diaz JJ, Dunham CM, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001;286:1841–1848.

- Como JJ, Diaz JJ, Dunham CM, et al. Practice management guidelines for identification of cervical spine injuries following trauma: update from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guidelines Committee. J Trauma. 2009;67:651–659.

- Burke CJ, Owens E, Howlett D. The role of plain films in imaging major trauma. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2010;71:612–618.

- Denver D, Shetty A, Unwin D. Falls and Implementation of NEXUS in the Elderly (the FINE study). J Emerg Med. 2015;49:294–300.

- Viccellio P, Simon H, Pressman BD, et al; NEXUS Group. A prospective multicenter study of cervical spine injury in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E20.

- Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Velmahos GC, Nance ML, et al. Clinical clearance of the cervical spine in blunt trauma patients younger than 3 years: a multi-center study of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2009;67:543–550.

- Hale DF, Fitzpatrick CM, Doski JJ, et al. Absence of clinical findings reliably excludes unstable cervical spine injuries in children 5 years or younger. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:943–948.

Jennifer Maccagnano, DO, is a emergency medicine attending physician at Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York, and is an Advanced Trauma Life Support instructor. She gained experience in urgent care while working at IHA Urgent Care–Domino’s Farms, in Ann Arbor, Michigan.