Urgent message: Urgent care providers are valued for their ability to treat nonemergent acute healthcare needs efficiently, but in so doing they are also well positioned to identify other, underlying healthcare issues such as hypertension.

Introduction

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and accounts for approximately 24% of all deaths.1 Many known risk factors are associated with heart disease, including high blood pressure. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 46,000 deaths each year may be prevented through effective treatment of hypertension, with an estimated savings of $93.5 billion in direct and indirect costs.2 However, due to its lack of outward signs or symptoms, high blood pressure often goes untreated. In fact, elevated blood pressure diagnosis often occurs secondary to other injuries and illnesses—many times in an urgent care setting.

Once identified, high blood pressure must be treated effectively, which includes follow-up care with a primary care provider (PCP), in order to reduce the morbidity and mortality rates associated with heart disease.

Urgent care facilities are engineered to treat nonemergent acute healthcare needs, but they are also an excellent source for identifying other underlying healthcare issues like elevated blood pressure. An estimated 3 million people are seen every week in urgent care facilities in the United States,3 and this number is increasing every year, offering new opportunities to address healthcare concerns like elevated blood pressure. Identifying and referring patients with undiagnosed and/or untreated elevated blood pressure during an urgent care visit is a relatively easy and inexpensive way to eliminate barriers in the treatment of hypertension. Follow-up appointments with a PCP may provide continuity of care through coordination and collaboration consistent with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) model for the Patient Centered Medical Home,4 resulting in better long-term health outcomes.

Little research exists on high blood pressure referrals and follow-up care in the urgent care setting or the emergency room setting. The Louisiana State University Public Hospital in New Orleans used a team approach to bridge the gap between newly diagnosed hypertensive patients in an urgent care facility and a PCP for ongoing evaluation and treatment. This method correlated with a study that evaluated the outcome of newly diagnosed hypertensive patients in an ED setting who were started on medications and then referred to a hypertension clinic for a team-approach follow-up appointment within 2 weeks. The results included a 12% increase in patients who had controlled blood pressure, as well as a reduction in healthcare costs.5

Another related study involved a nurse-led hypertension referral program for ED patients with blood pressure >140/90 mmHg. When contacted, 136 out of 222 were followed up for their blood pressure by a PCP after being given a referral at the time of discharge.6 The American College of Emergency Physicians’ Policy Statement on the evaluation and management of asymptomatic hypertension, >140/90 mmHg, includes a referral for outpatient follow-up care.7 Shamji, et al8 addresses one of the major issues with urgent care referrals, which is the lack of guidelines for care transitions from the urgent care setting to a PCP, and notes that for patients without a PCP, the urgent care center may be an important opportunity to establish a referral for the patient to a PCP in the community.

As a quality improvement initiative and for my doctoral project, I designed and implemented a project in the Matagorda Medical Group Urgent Care (MMGUC), a rural urgent care facility in Matagorda County, TX to determine whether subjects age 18 years and older who were seen and identified with elevated blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg) were more likely to follow up with a PCP if an appointment was established prior to discharge from urgent care, compared with subjects who were identified with elevated blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg and were told to follow up with a PCP but did not have an appointment made for them prior to discharge from urgent care. The aim of the project was to increase the number of subjects evaluated further by a PCP after being identified with elevated blood pressure during an urgent care visit.

Quality Improvement Project Results

A retrospective chart review was conducted using electronic medical records (EMR) to identify 50 adult subjects who were treated in the MMGUC for urgent illnesses or injuries and who also had elevated blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, to determine whether or not they followed up with a Matagorda Medical Group PCP at 2, 3, or 4 weeks post urgent care visit. This was then compared with a prospective chart review that was conducted using the EMR to track the 50 consented adult subjects (age 18 years or older) who were treated in the MMGUC for urgent illnesses or injuries and who also had elevated blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, to determine whether or not they followed up with a Matagorda Medical Group PCP as scheduled by the MMGUC receptionist prior to discharge from the urgent care.

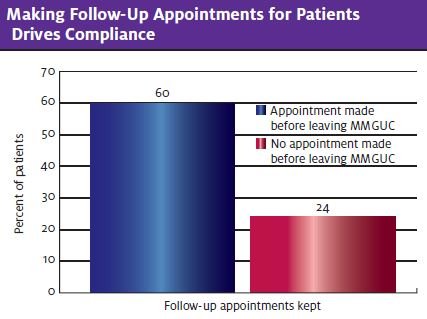

Twenty-four percent, or 12 of the 50 subjects, identified in the retrospective group who did not have appointments made for them by the MMGUC staff followed up with a PCP within 4 weeks of the urgent care visit. Sixty percent, or 30 of the 50 subjects in the prospective group who did have appointments made for them by the MMGUC staff, followed up with a PCP within 4 weeks of the urgent care visit. Both an independent samples t-test and a chi square test of independence were calculated to determine if this information was statistically significant.

The independent samples t-test was used to determine whether membership in the retrospective or prospective group had an impact on whether the subject was seen in a follow-up appointment with a PCP (yes or no) within 4 weeks post urgent care visit. Levene’s test for equality was violated at F = 11.036, p = 0.001, so the t-test results required the use of unequal variances not assumed. The failure to have an equal variance was due to the large difference of 30 prospective subjects that were followed-up by a PCP compared with 12 retrospective subjects that were followed up by a PCP. Since the prospective group was larger in follow-up than the retrospective group by 18 subjects, it violated the assumption that both groups had equal variance. However, after correcting for the unequal variance, a significantly higher difference was noted in the t-test with the prospective group mean of 0.60 (N = 50, SD = 0.495) compared with the retrospective group mean of 0.24 (N = 50, SD = 0.495) at t (96.211) = 3.877 (p < 0.0001). In addition to the t-test, the same data were used to calculate a chi-square test of independence, and was significant at 13.300, df = 1, p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Making an appointment for subjects with a PCP prior to discharge from the MMGUC significantly increased the number of subjects who followed up with a PCP for further evaluation of their elevated blood pressure according to the independent T-test for this group. The chi-square test was also significant for this group, showing a strong association with follow-up care and making appointments for subjects prior to discharge from the MMGUC. These findings are consistent with literature discussed above regarding improved outcomes when follow-up appointments were made for subjects with high blood pressure seen in emergency and urgent care centers.

Recommendations

Urgent care facilities must develop policies that enable continuity of care through coordination with primary care providers. Scheduling an appointment prior to discharge from an urgent care center can improve access to care and empower patients to take an active role in their own healthcare. Improving collaborative efforts may result in a strong patient-centered team that focuses on the individual needs of the patient, with a goal of increasing the longevity and quality of life for the patient while decreasing the overall cost and disabilities associated with untreated high blood pressure.

Effective collaboration also relies on the use of health information technology for managing chronic health conditions like hypertension. Establishing an interoperable healthcare system that allows the free exchange of healthcare information among the healthcare team would allow continuity of care between the patient’s PCP and the urgent care provider. Unfortunately, few health information systems are able to communicate outside of their own providers. This makes it difficult for individual urgent care facilities and/or individual primary care providers to share information in a timely manner.

More research needs to be done in urgent care settings to establish best practice. This project introduced an intervention of making appointments with PCPs for subjects with elevated blood pressure during an urgent care visit to address the issue of whether or not it would improve the number of subjects who were followed up by a PCP. This was the only variable addressed as to why subjects did not follow up with a PCP after being diagnosed with elevated blood pressure. While the results were significant for this group, this study would need to be duplicated in other settings and other variables need to be considered to determine additional barriers to follow-up care with a PCP for patients diagnosed with elevated blood pressure.

Conclusion

Early detection and proper treatment of elevated blood pressure may improve health and decrease costs associated with the number-one cause of death in the United States, heart disease.

While this study has limitations, the results were consistent with other research that supports making referrals for follow-up care prior to patients leaving EDs or urgent care facilities. Future challenges include developing policies that ensure continuity of care between urgent care facilities and PCPs, developing healthcare systems that allow electronic medical records to be shared between urgent care facilities and PCPs, and doing more research that can be used to develop best practice policies and plans for the future.

References

- Heron M. (2013). Deaths: Leading causes for 2010. National Vital Statistics Report. 2013;62 (6). National Center for Health Statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_06.pdf.

- Yoon P, Gillespie C, George M, Wal, H. Control of hypertension among adults—national health and nutrition examination survey, United States, 2005–2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6102a4.htm

- Galewitz P. Urgent care centers are booming, which worries some doctors. Kaiser health News. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2012. Available at: http://kaiserhalthnews.org/stories/2012/september/18/urgent-care-centers.aspx?referrer=search.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient centered medical home resource center. Available at:mhttps://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

- Traynor K. Team approach best for hypertension management. American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacist. Available at: http://www.ashp.org/menu/News/PharmacyNews/NewsArticle.aspx?id=3731.

- Tsoi L, Tung C, Wong E. Nurse-led hypertension referral system in an emergency department for asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18(3):201-206.

- Pirotte M, Buckley B, Lerhmann J, Tanabe P. Development of a screening and brief intervention and referral for treatment for ED patients at risk for undiagnosed hypertension: a qualitative study. J Emerg Nursing. 2014;40(1):e1-e9.

- Shamji H, Baier R, Gravenstein S, Gardner R. Improving the quality of care and communication during patient transitions: Best practices for urgent care centers. Jt Comm J Qual and Patient Saf. 2014;40(7):319-324.

Barbara Hayes, DNP, FNP-C