Urgent message: Availability of hospital-affiliated urgent care can not only lower the burden on overcrowded EDs, but also help capture new business and keep existing patients within the health system.

Hospitals have operated urgent care centers for over 25 years; today, estimates of how many centers are affiliated with hospitals range from 15% to 20%. In recent years, hospitals grappling with overcrowded emergency rooms and increased competition for outpatient visits have rediscovered urgent care as a way to shift low-acuity cases out of the ED while increasing revenue for affiliated providers and ancillary services.

The Cause of Long Emergency Room Waits

Over the past 10 years, private and government payors have focused on reducing inpatient hospital stays as a way to curb rising healthcare costs. In response, hospitals have invested in new clinical technologies and elegant outpatient facilities. These neighborhood facilities— often anchored by an ambulatory surgery center—host a myriad of integrated services, including diagnostic imaging, physical rehabilitation, women’s health, occupational medicine, and sleep services.

Despite an aging population and deteriorating personal health, the combined efforts of hospitals and payors have been successful in reducing inpatient days per 1,000 approximately 7% between 1999 and 2006, according to the Kaiser Family Health Foundation.

Progress, indeed—but with an unintended consequence.

Up to 40% of hospitalemergency departments are overcrowded, the Institute of Medicine reported in 2006. Average wait times in hospital EDs have increased each of the past 10 years; in some cities, the time to be treated and discharged by an emergency physician is now eight hours or longer, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The leading cause of emergency room overcrowding is the declining number of inpatient beds due to falling reimbursement and the shift to outpatient facilities, concludes the American College of Emergency Physicians. Without enough inpatient beds, hospitals “board” more patients in their emergency departments— which occupies beds there and increases wait times for new patients.

A Solution for Crowded Emergency Rooms

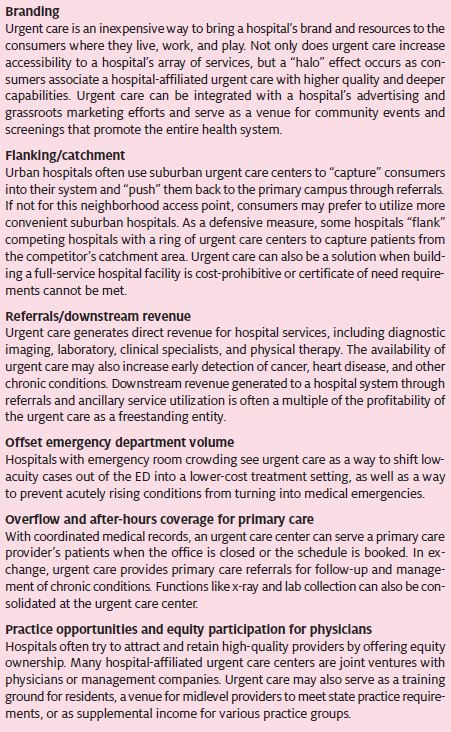

Of all the reasons hospitals are interested in urgent care (Table 1), it seems the most common is to decompress an overcrowded ED. Besides long wait times, emergency room crowding makes it difficult to hire and retain good emergency physicians and nurses, increases the potential for medical errors, prolongs pain and suffering, and diminishes patient satisfaction.

In addition, ambulance diversion to other facilities can cause life-threatening treatment delays and preclude a hospital’s ability to handle any type of volume “surge”—an essential defense against terrorist attack or natural disaster. Up to 70% of emergency room visits could have been treated in a lower-acuity setting or avoided altogether if early treatment had occurred before the condition progressed into an emergency, states a 2005 New York University study.

Between 1996 and 2006, visits to hospital emergency rooms rose from 90 million to 119 million—a 32% increase, according the CDC. And in 2007, the Advisory Board Company, which conducts best practices research and analysis, projected that annual ED visits will continue to increase to roughly 124 million by 2015. If low-acuity patients could be treated in settings other than hospital emergency departments, capacity would be freed to focus on trauma care and hospital admissions.

ED Resistance to Urgent Care

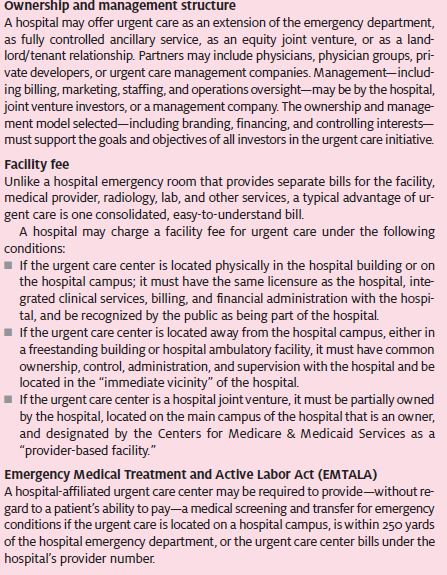

When a more convenient, lower-cost alternative to the ED is made available, it’s logical that consumers will use it. The challenge for some hospital and emergency department administrators is that while emergency room charges can be four to six times higher than urgent care, the incremental cost of treating a low-acuity patient in the ED can be very low, provided all resources are already in place. And when low-acuity patients have good insurance, their visits often subsidize losses on charity care and public assistance programs.

High margins from low-acuity, privately insured patients incentivize many hospital emergency departments to advertise “fast tracks,” “service guarantees,” and “zero wait” policies. The legitimate fear among administrators is that losing privately insured and self-pay patients to urgent care will adversely affect ED margins. Because even when urgent care is available, there is a base of lower-margin patients—including Medicaid, indigent, mentally ill, and non-working uninsured populations— who are unlikely to change their behavior of using the ED as a stop-gap or access point for primary care.

Urgent Care as an Alternative to the Emergency Room

Despite concerns that urgent care will “cherry pick” the most profitable ER cases, studies show the percentage of indigent or charity care patients presenting to the ER with low-acuity conditions is relatively low. A 2005 report in the Annals of Emergency Medicine indicates that as many as 85% of emergency room patients have health insurance and 70% have incomes above the federal poverty level. Many patients use the ED not because they have to but because they want to.

Affluent and fully insured patients expect convenience and demand quality hospital emergency rooms are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week and consumers perceive that hospital affiliation and staffing by emergency physicians results in broader capabilities and a higher standard of care.

In order to woo premium patients away from the emergency room, urgent care must offer a superior experience one that is closer to home, has shorter wait times, incurs less hassle with billing, and is delivered in a warm and friendly atmosphere.

Lower copays built into an increasing number of insurance plans also help direct patients to urgent care, as do high-deductible health plans that make consumers responsible for the cost of their visit. If hospitals don’t embrace urgent care, emergency room capacity problems will only get worse and insured patients will be targeted by entrepreneurial urgent care centers, retail health clinics, walk-in family practices, and other delivery models.

Each of these emerging players promotes itself as an “alternative to the emergency room,” and while they may help the hospital achieve its goal of offsetting ED volume, in many cases they will not contribute anything back to the hospital in return for the revenue lost.

Downstream Referrals Generated by Urgent Care

Hospital-affiliated urgent care allows hospitals to offset ED volume but still build their revenue base. When urgent care is integrated with affiliated practice groups and ancillary services, it becomes an entry point to the health system. Pediatrics, internal medicine, orthopedics, physical medicine, general surgery, and podiatry are just a few of the specialties that benefit from urgent care referrals.

Moreover, urgent care provides direct revenue to hospital ancillary services like diagnostic imaging, laboratory, and physical rehabilitation, which are also utilized by referral providers. The degree to which urgent care is integrated with affiliated providers and ancillary services—including location in the same facility, shared electronic medical records, and consolidated billing— influences how effective the health system will be in capturing referrals and retaining downstream revenue.

In addition to supporting existing services, a professionally staffed and wellequipped urgent care provides visibility and access to consumer and business markets allowing a hospital to enter new lines of business such as occupational or travel medicine. These new business lines generate additional referrals and further utilization of ancillary services. Hospitals may also use the urgent care center to make services otherwise provided in the hospital such as laboratory collections more convenient for consumers.

‘Front Door’ to the Health System

The result of fewer inpatient admissions and continued hospital investment in outpatient capabilities is increased competition among hospitals in many communities— with hospitals trying to establish themselves as having the most locations, greatest patient satisfaction, highest quality rankings, and widest

range of capabilities to attract new patients and retain providers.

The very essence of urgent care is that it is a consumer-centric healthcare delivery model a convenient, extended hours, walk-in facility. Urgent care can establish a hospital’s brand in a community and provide a “front door” by which consumers can access all of the hospital’s services. While hospital urgent care does face some unique operational challenges (Table 2) not common to independent, freestanding urgent care centers, hospitalbranded urgent care centers benefit from the halo effect described previously.

Although the case for hospital urgent care is appealing on the surface, in practice it isn’t so cut-and-dried. Hospitals are large, complex organizations filled with a spectrum of financial, social, and clinical interests which need to be continually reconciled. Therefore, the business case for urgent care needs to be carefully constructed to meet the expectations of all interested parties in an integrated health system.