Urgent message: Once a rarity in the urgent care setting, point-of-care ultrasound imaging capabilities are on the rise in our industry. Falling prices and increased portability provide new opportunities to manage more patients on site, facilitating better outcomes and higher patient satisfaction for many.

James Hicks, MD

The Case

An 85-year-old resident of an assisted-living facility presents to the urgent care center in early autumn with complaints of wheezing. Staff are concerned that she has bronchitis.

On physical examination she is an afebrile elderly woman with diffuse bilateral wheezes but good air exchange. She isn’t dyspneic and is speaking in full sentences. Rapid flu testing is negative. Rather than doing a chest x-ray, a handheld ultrasound is used along with a preset, software-guided lung protocol and demonstrates small bibasilar pleural effusions and an abnormal presence of “B-lines,” a hyperechoic reverberation artefact that correlates with interstitial syndromes, in this case pulmonary edema. Rather than placing the patient on beta adrenergic medication or antibiotics, her diuretic is adjusted with close primary care follow-up.

Growing Use of Ultrasound in Urgent Care

With lower cost and increased portability, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is an increasingly appealing tool for the urgent care provider. The technology is easy to deploy, and its ability to complement and extend the physical exam allows expanded assessment of the urgent care patient. There is potential for more accurate and timely diagnoses with shorter time to treatment and improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.1

As POCUS evolves and longitudinal training disseminates via medical schools and residencies, it is likely that use of portable ultrasound technology will expand into many areas of medicine, including urgent care.

Our urgent care centers see a high-acuity patient population and POCUS has been of value in sifting through some of the more complex comorbidities. Of particular value has been the patient presenting with a swollen leg and concern for DVT.2 Especially for those with low pretest probability, the ability to effectively rule out DVT has been of enormous value in saving patient time, frustration, and cost. In the urgent care setting, lung exam using handheld ultrasound (HHUS) has also been valuable in evaluating shortness of breath, pneumothorax, and pleural effusion.

Musculoskeletal abnormalities have been easier to manage, as well. The physical exam is difficult in acutely injured patients, but ultrasound allows a gentler evaluation of the rotator cuff or any tender joint. Suspected fractures can be evaluated in children and others where even minimal radiation exposure is a consideration. We have found the ability of ultrasound to clarify cellulitis vs abscess useful, particularly in avoiding incision in the absence of a cavity.

Evaluation of urinary retention has been convenient and accurate, sparing patients increased imaging, delay in treatment, and embarrassment.

The best part of the offering is the adaptability of POCUS: The clinician can tailor skills to the needs at hand; if all you ever learned was musculoskeletal ultrasound, you would still be doing your patients an enormous service. At the end of day, this is our goal.

Current State of Affairs

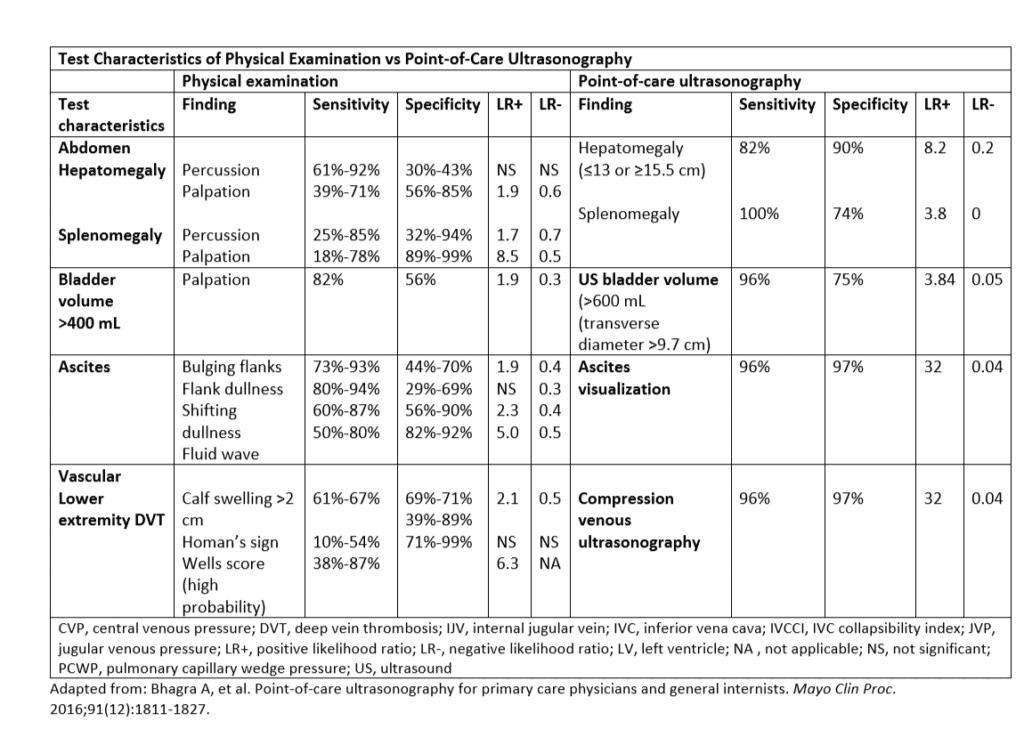

The accuracy of the traditional physical exam has been re-evaluated as evidence-based clinical elements are reviewed.3 Current POCUS testing can improve the physical exam quality and accuracy. As an example, physical exam can be expected to detect a DVT with a sensitivity and specificity of 65%-70%. By adding POCUS, sensitivity and specificity are 96% and 97% respectively, with positive likelihood ratio of 32.4

Many urgent care centers do not have access to in-house imaging beyond plain film radiography, leading to limitations in assessment. Examples include pregnancy-related issues, DVT evaluation, and abdominal pain. The need to refer these patients for more advanced imaging increases emergency room utilization and advanced imaging costs, adding unnecessary testing hurdles for patients.5

The AMA considers POCUS to be part of scope of practice for “appropriately trained physicians.”6 The American College of Emergency Physicians has a policy statement from 2016 which outlines training, proficiency, and credentialing. It states that:

“…the clinician needs to recognize the indications and contraindications for the EUS (emergency ultrasound) exam. Next, the clinician must be able to acquire adequate images. This begins with an understanding of basic US physics, translated into the skills needed to operate the US system correctly (knobology), while performing exam protocols on patients presenting with different conditions and body habitus. Simultaneous with image acquisition, the clinician needs to interpret the imaging by distinguishing between normal anatomy, common variants, as well as a range of pathology from obvious to subtle. Finally, the clinician must be able to integrate EUS exam findings into individual patient care plans and management.”

The AAFP produced guidelines for training in 2016, as well, which recommend: “150 to 300 total scans for general point-of-care ultrasound competency, 25 to 50 supervised exams for a specific diagnostic exam, and five to 10 supervised scans for ultrasound-guided procedures.”7

There is less available research on handheld ultrasound. What data are available suggests improved diagnostic value using handheld devices even with basic training.

It may be most appropriate for the usual urgent care provider to consider the “ultrasound-assisted examination.”8 This approach combines the examination talents of the provider with extension of their skills via POCUS technology to reach a diagnostic conclusion, a hybrid approach that has better sensitivity in spotting pathology. Protocols adapted for the outpatient setting (the “PEARLS” protocol,9 for example) are beginning to emerge, adapted from validated emergency medicine techniques. With adequate training and use of such protocols and targeted scanning, most scans can be completed in a few minutes.

The Technology

Currently, POCUS devices range from handheld devices that connect to a phone or tablet screen to laptop-sized devices which have the capability of advanced image manipulation and storage options. Handheld devices are smarter than ever, with selectable preset imaging choices and image enhancement offering a range of portability, resolution, and cost options. Other features such as internet and PACS connectivity allow image integration with EMRs or storage for QA and archival purposes. Choices in portability may define scalability and realistic purposing: for most providers a handheld unit will not be sufficient to evaluate for appendicitis the same way larger units might. As the market matures, additional choices in hardware and software will allow adaptability for particular institutional needs.

Examples of POCUS applications in the urgent care center can include:

- EENT: FB eye, retinal detachment

- Lung: pneumothorax, pleural effusion, pneumonia

- Cardiac: pericardial effusion, CHF, IVC fluid status

- MSK: tears, effusion, evaluation of abscess vs induration, cellulitis vs fasciitis vs abscess, fracture identification, foreign body

- Abdomen: Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

- Pelvis: GB and liver evaluation; bladder scan; basic pregnancy; hydronephrosis

Upsides

There appears to be an increase in patient satisfaction when POCUS is utilized.10 Patient satisfaction may be enhanced by decreased stay, shorter test-to-treatment time, streamlined disposition, and improved patient outcomes.

For example, delineating cellulitis vs abscess may avoid unnecessary procedures or guide more thorough drainage when an abscess is present. Joint injection efficacy and safety are enhanced by using ultrasound.11

In practical use, POCUS may help clarify clinical scenarios beyond the abilities of the physical exam. In a fascinating study, first-year medical students with no clinical experience but 18 hours of handheld ultrasound training had greater diagnostic accuracy for LV dysfunction than the physical exam by cardiologists.12

For the urgent care provider, it is possible that POCUS can reduce upstream costs.13 The POCUS examination for DVT takes just a few minutes to perform and has a sensitivity and specificity of 96/97% and a negative LR of 0.04.3 Ruling out the common ultrasound presentation of leg swelling can save patients considerable time and expense; the usual cost for a venous Doppler of the LE s is approximately $750, excluding radiologist fees.

- Avoidance of ER referrals or “STAT” imaging charges

- Avoidance of more advanced imaging

- Patient education and treatment reinforcement

- Improved therapeutic interventions, ie, joint injections, abscess drainage

- Improved outcomes of diagnostic homonyms: asthmatic bronchitis vs cardiac asthma

- Clear benefits in certain areas (pneumothorax, urinary retention)

- Shortened test to treatment time

- Advantageous in educating patients

- Possible return on investment in fee for service practices14

Challenges

Beyond the cost of the equipment, there is the cost of training. Introductory courses seem to be springing up, but the number of examinations required to demonstrate proficiency is not clear and is likely variable depending on the application and prior training of the examiner. There are a number of interesting simulation labs available both as physical and online entities, and use of a modular educational approach allows providers to tailor ultrasound education to their particular needs. There are no set numbers for proficiency, and as POCUS is considered “scope of practice” for most physicians, there are no enforceable guidelines to gauge quality and proficiency. However, it appears that even minimal training improves diagnostic accuracy for many clinical presentations.15

At present, there is no clear curricular path for the urgent care provider. Emergency room physicians working in urgent may have qualifications under ACEP-delineated training pathways such as Residency-, Practice-, and Fellowship-based training. Any credentialing path is within the purview of the specialty itself, making such clarity for urgent care mercurial. Some discussions even question the rationale for any credentialing process, favoring demonstrated competency in a similar fashion to use of stethoscopes.16

Similarly, issues regarding quality assurance are nebulous. Should the images be over-read by a radiologist? What should be the nature of that relationship along with cost and liability issues? Do images need to be archived or integrated into the EMR? Is it sufficient to record our findings much as we would stethoscopic results? Are handheld devices held to a similar standard as traditional table top ultrasound machines with higher resolution?

Some of those questions interrelate with the issue of billing for POCUS. Medicare currently suggests it “will generally reimburse physicians for medically necessary diagnostic ultrasound services, provided the services are within the scope of the physician’s license and for the indications outlined in the NCD.” Some Medicare administrative contractors (MACs) require that the physician who performs and/or interprets some types of ultrasound examinations are capable of demonstrating relevant, documented training through recent residency training or post-graduate CME and experience.17

The ability to bill for many POCUS services is not clear for all uses. Depending on contractual arrangements, POCUS may not be at all reimbursable as in case-rate reimbursement. But Medicare reimbursement tables are available using nonhospital settings with a “limited” descriptor. Examples include chest, abdominal, and extremity studies. There are several codes for ultrasound-assisted vascular access or aspiration/injection of joints or soft tissues. Ultrasound services performed with a portable or handheld ultrasound system must meet the requirements of medical necessity set forth by the payer and meet the requirements of completeness for the chosen code, with a procedure code documented in the patient record. Accompanying this would require a QA system as well as image archival.

Point-of-care ultrasound costs are coming down rapidly, particularly in the realm of handheld devices. Urgent care providers might consider researching the technology and training, and consider whether the time is now for use of POCUS in the urgent care setting.

References

- Howard ZD, Noble VE, et al. Bedside ultrasound maximizes patient satisfaction. J Emerg Med. 2014; 46(1):46-53.

- Juhar S. The demise of the physical exam. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:548-551.

- Bhagra A, Tierney D, et al. Point of care ultrasonography for primary care physicians and general internists. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016; 91(12): 1811-1827.

- Colli A, Prati D, Fraquelli M, et al. The use of a pocket-sized ultrasound device improves physical examination. PLOS One. 2015. Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0122181. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- 802, I-99; Reaffirmed: Sub. Res. 108, A-00; Reaffirmed: CMS Rep. 6, A-10.

- Melniker LA. New AMA resolutions to promote point-of-care clinical ultrasound. American College of Emergency Physicians. Available at: https://www.acep.org/how-we-serve/sections/emergency-ultrasound/news/december-2016/new-ama-resolutions-to-promote-point-of-care-clinical-ultrasound/#sm.000gnvvycri7f7c10vb2ankvnmrih. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Point of care ultrasound. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint290D_POCUS.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- Friedell BN. Ultrasound-assisted physical examination. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):182, 185.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YOzi6rnE5qo

- Royse CF, Canty DJ, Faris J, et al. Core review: physician-performed ultrasound: the time has come for routine use in acute care medicine. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(5):1007–1028.

- Martin EJ, Cooke EJ, Ceponis A, et al. Efficacy and safety of point-of-care ultrasound-guided intra-articular corticosteroid joint injections in patients with haemophilic arthropathy. Haemophilia. 2017;23(1):135-143.

- Kobal SL, Trento L, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of hand-carried ultrasound to bedside cardiovascular physical examination. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(7):1002-1006.

- Mercaldi CJ, Lanes SF. Ultrasound guidance decreases complications and improves the cost of care among patients undergoing thoracentesis and paracentesis. Chest. 2013;143(2):532-538.

- Nguyen D, Espinosa RF, et al. Would hospitalist use of point-of-care ultrasound pay for itself? J Hosp Med. https://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/would-hospitalist-use-of-point-of-care-ultrasound-pay-for-itself-a-return-on-investment-prediction-model-using-unincentivized-ultrasound-trained-residents/. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- Bornemann P, Jayasekera N, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound: coming soon to primary care? J Fam Pract. 2018;67(2):70-80.

- Monti J, Norman F. POCUS Certification: A Solution to a Problem that Doesn’t Exist. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/pocus-certification-solution-problem-doesnt-exist-care-ultrasound. Accessed October 26, 2018.

- Primary Care. Available at: https://www.sonosite.com/sites/default/files/2018-SonoSite-Primary_Care-01082018.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2018.

James Hicks, MD is Lead Physician, Urgent Care, for Hudson Headwaters Health Network in

Queensbury, NY.