Urgent message: Despite the current seasonal, postpandemic lull in volume, sophisticated investors are focused on the long-term growth prospects of urgent care in terms of new rooftops, new patient populations, new services, and new payers…among others.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc

Even for those who are “tenured” in the urgent care industry—the last 24 months of the COVID-19 pandemic have been a rough ride. If 100% were baseline volume, the average urgent care saw volume increase by 71% then fall 58% before and after Alpha, rise another 80% before falling 30% for Delta, and then rising 90% for Omicron before falling 69%, stabilizing back to 2019 volumes.1 Even if as an urgent care owner or operator you’re exhausted, you should know that “big money” is energized.

The fact of the matter is, we’re seeing an influx of capital by new and existing investors who see a compelling investment thesis in urgent care based on:

- Rooftop growth and patient growth

- COVID patient retention

- Provider cash on hand

- New patient populations

- Service extensions

- PE- and hospital-funded consolidation

According to a report from the University of California at Berkeley,2 private equity investments in healthcare over the last decade have exceeded $750 billion, a trend that’s expected to accelerate in coming years. In 2020, 77.4% of deal volumes involved clinics and outpatient services.2 In urgent care, specifically, private equity invested in 182 deals from 2012 to 2020, representing approximately 50% of all urgent care transactions.3

Rooftop and Patient Growth

From 2013 to 2021, the industry saw a 7.5% annual growth rate in new centers or “rooftops” with an underlying 4% to 7% annual growth in same-center patient volumes4—a trend that’s expected to continue in coming years.

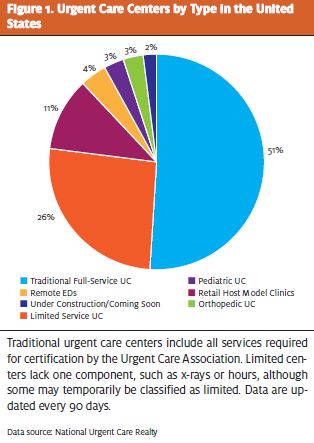

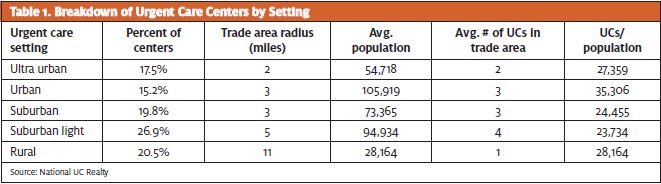

The United States has between 8,000 and 16,000 “on demand” healthcare centers, depending on the definition you use, as illustrated in Figure 1. Using a round number like 10,000 centers (which includes all that qualify for urgent care certification by the Urgent Care Association), there’s approximately one center per 34,000 people in this country of roughly 340,000,000. Based on this population, average patient utilization, and average center capacity, the country could support two to three times as many centers as it currently has.

Furthermore, when you break it down by state, the distribution of urgent care centers is wildly uneven. Some states like Tennessee have strong coverage with one center per 25,000 people but others, like California and Illinois (both one center per 42,000) or Texas, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina (all one center per 38,000) have populations that remain largely underserved by urgent care.4

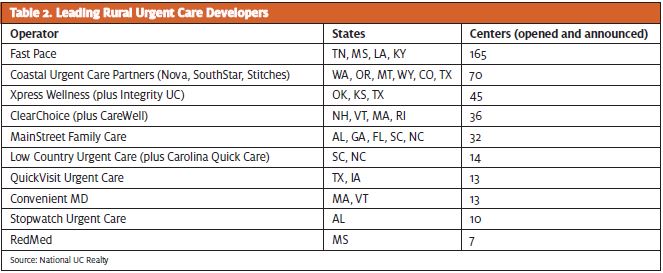

According to National Urgent Care Realty,5 nearly half the nation’s urgent care centers are in suburban settings. While there’s still “white space” available in every setting, locating in increasingly crowded suburban markets requires a more strategic approach to site selection in order to outposition competition. Meanwhile, developers can open centers in historically under-represented urban and rural areas with little competition leading to more rapid profitability.

Additionally, we expect a continuation in patient volume growth as new locations add capacity. As noted previously, pre-pandemic, we saw average growth in patient volumes at 4% to 7% per year, driven by payer steerage and local marketing driving consumer awareness—a trend that will continue as centers fill their excess capacity and as new patient populations are introduced to urgent care.

COVID Patient Retention

At the “peaks” of the pandemic, the “average” urgent care was seeing over 70 patients per day, according to Experity data3 which, extrapolated, translates from 700,000 to over 1 million patients per day for the industry. In 2021, nearly 50% of all patients who entered an urgent care center did so for COVID-related concerns. This introduced urgent care to a whole lot of new people.

That’s fine, but…will they return? Were they tested in a parking lot? Did they have to wait hours or days for an appointment? Was the center adequately staffed with adequate PPE? How many days did the PCR COVID test results (before rapid testing) take? Not everyone had a great experience with urgent care during the pandemic.

On a more positive note, Experity research reveals that 64% of “new” patients—those who first used urgent care for COVID-related reasons during the pandemic—plan to use urgent care again when future non-COVID, urgent care-type complaints arise. This is almost at the “established user” rate of 77%. And given that the “average” urgent care patient visits a center 1.7-2.0 times per year, this translates to a lot of future visits for urgent care centers.

With such a rich database of patients, it is incumbent upon urgent care centers to recapture these patients through digital and conventional marketing, including text and email campaigns, targeted digital display advertising, search engine marketing, and direct mail (among others).

The opportunity is to educate patients as to the center’s complete offerings and to keep the center top of mind for future episodic medical needs.

Provider Cash on Hand

As a result of record volumes during the pandemic, many providers are now flush with cash. Where are they going to invest it? Real estate is in a bubble. The stock market is volatile. Interest rates are still low, making savings unattractive, and rising interest rates also lead to falling bond prices. All of this points to their “best investment” being their own successful business.

Taking a long-term view, savvy urgent care operators see that low interest rates and rising inflation create a situation in which money borrowed today at low rates becomes essentially “free” when paid back with inflated dollars. Landlords burnt by pandemic closures of restaurants and specialty stores are eager to “deal,” meaning high-visibility spaces have not only opened up, but landlords are increasingly willing to give “free” rent and other incentives, enabling urgent care operators to sit on space for 6 to 12 months until they’re ready to open.

Not only does cash on hand enable operators to weather any seasonal lull, but given urgent care is a volume-based business (meaning once a sufficient number of visits are attained to cover fixed costs, each incremental visit flows to the bottom line), retention of COVID patients and an endemic COVID mean urgent care centers will hit break-even volume faster than ever.

Cash on hand plays a vital role in the urgent care growth story as existing operators have never been in a better financial position to expand.

New Patient Populations

As urgent care grows in historically underserved markets, entire new patient populations are introduced to the operating model. For instance, rural populations tend to be older (33% >55-years-old vs 26% in suburban markets), less affluent ($64,000 median household income vs $84,000) and less reliant on commercial insurance (66% vs 74%). This geographic difference in payer mix includes not just Medicare for Seniors, but rural populations are 36% more likely than suburbia to be on Medicaid.

Until recently, there was no Medicaid contract for urgent care in most states. A center could contract as a primary care but that imposed “medical home” requirements, including 24-hour on-call access and hospital admitting privileges, which weren’t conducive to an episodic, walk-in model. Low rates also didn’t cover the expense of x-ray, procedures, and labs performed in urgent care.

Two of the most compelling developments in urgent care have been its recognition by Medicaid payers and the proliferation of rural urgent care footprints.

A patient with commercial insurance is going to face a $100+ copay for the ED. Plan design has curbed excess ED utilization among privately insured patients. However, for Medicaid patients, the ED is essentially “free,” leading many patients who lack health access to rely on emergency medicine for primary care. As a result, health outcomes among rural populations have been poor.

Medicaid expansion and the proliferation of urgent care centers in rural communities are helping close a gap in health equity, especially in the light of rural hospital closures. Innovative urgent care providers are extending their services. Medicaid payers are recognizing urgent care’s cost savings with preferred reimbursement.

Operators report rural markets entail lower operating overhead, loyal and grateful providers and staff, and a faster ramp-up to break-even volumes by adding something that didn’t previously exist: people no longer have to drive 30, 45, or 60 minutes for episodic care. Access to quality, brick-and-mortar healthcare lifts entire communities.

Service Extensions

Urgent care should remain focused on high throughput, short waits, and high provider efficiency for the 80% of visits that are the 15-20 most frequent diagnoses. When an urgent care center starts focusing on services other than this core competency of acutely rising sick and injured, it could indicate the center is not executing well as a truly urgent care business.

It’s also easy for management to become distracted by “bright shiny objects” and thus take their eye off the ball.

However, there are times when an urgent care center cannot avoid excess capacity due to seasonality, ebb-and-flow throughout the day, and the incremental nature of provider scheduling. In these instances, an urgent care center can increase its revenue and maintain its productivity by adding ancillary services.

Occupational medicine, which for urgent care primarily entails drug screens and multicomponent physicals, tends to be busiest in the summer months when companies are hiring and construction projects are in full swing. Summer historically is a lull from cold/flu season highs. Appointments can be steered towards slow times of day. Additionally, except for workers comp injury care, employer-paid services such as audiometry, spirometry, TB testing, and respirator fit testing can be easily performed by trained medical assistants, meaning they don’t add significantly to labor costs.

Many employers are dissatisfied with their current options for occ med—including hospital programs and national chains. Although national accounts like Walmart, FedEx, and UPS may take time to cultivate, every municipality has compliance needs related to police, fire, sanitation, animal control, schools, parks and recreation, schools, bus transit, and other functions.

Apart from occ med, ancillary services that seem to be gaining traction in urgent care include:

- Physical therapy

- Primary and preventive care

- Behavioral health

- Specialist services (allergy, ortho, dermatology, etc.)

- Medication Assisted Treatment (Suboxone)

- Weight management

- Medical aesthetics and IV hydration

Ancillary services that complement the core urgent care business can be a way of expanding revenue in, say, rural markets that have finite demand. For example, some operators have formed management services agreements with specialists who can follow up on the center’s patients one or two days a week. It is very difficult for Medicaid and Medicare populations to access dermatologists, for instance, for preventive care like wart and mole removal. That’s because many dermatologists are focused on a suburban, cash-pay, cosmetic clientele. During the week there is opportunity to aggregate demand for a specialist that may not otherwise be accessible in the community, creating a new revenue stream for urgent care and improving healthcare accessibility and outcomes for patients.

In short, adding new services is a way to increase total revenue, fill excess capacity, and increase a patient’s visit frequency beyond episodic sick visits.

Private Equity- and Hospital-Funded Consolidation

Beyond the returns achieved by expanding the price-earnings multiple of add-on practices attached to desirable platform investments, investors hypothesize that roll-up or buy-and-build strategies can yield administrative economies of scale and improved bargaining leverage with insurers in price negotiations that can improve profitability.

As a result, and as we predicted in JUCM in December, 2021,6 we’re already seeing mergers of private equity-backed urgent care entities in adjacent markets. Compared with the time it takes a de novo to open and break even, an investor can add immediate revenue, cash flow and EBITDA by folding in strategic acquisitions. This means “onesies” are becoming “twosies,” local platforms are becoming regional platforms, regional platforms are becoming super-regional platforms, and so on.

When talking mergers and acquisitions, we must remember that urgent care is a local business, and the greatest synergies of a multilocation footprint are in a single geography. “One here, two there, three over here” creates challenges with management oversight, adds administrative costs, and weakens team accountability.

By contrast, a mass of centers in a single geography enables a bench of providers to be more efficiently deployed according to demand, a larger marketing budget enabling mass media that benefits all centers (reducing the advertising spend required per location), and greater “stickiness” for employers and health plans who cannot sell their network without participation of the “favorite” urgent care chain.

On a local level, acquisitions will largely be driven by hospitals and health systems seeking to expand their brand catchment and capture greater downstream referrals.

Today, approximately 43% of urgent care centers have a health system “affiliation.”5 But the nature of the affiliation can look very differently depending on the hospital. In some cases, urgent care is owned and operated by the local hospital as a stand-alone entity. In others, it’s part of a primary care or multispecialty group affiliated with the health system.

And, perhaps, what’s increasingly the most common arrangement is where a private third party (including independent physicians and PE-backed platforms) have full management and operational control of a center cobranded with the hospital, which can be a joint venture, management services, landlord/tenant relationship, and/or a downstream referral agreement.

So, not only do we expect hospitals to buy local centers, but we expect new rooftop growth through partnership agreements between private urgent care developers and health systems.

Conclusion

Before the pandemic, there may have been reasons to be concerned about urgent care’s ability to sustain it’s 2010-2019 growth rates. But as urgent care stepped up to the challenge of COVID-19, such created wind in the sails by establishing urgent care’s role in the nation’s healthcare framework, introducing millions of new consumers to the model, providing capital for future expansion, and raising the visibility of the industry to new investors.

References

- Proprietary data, Experity, Inc.

- Scheffler RM, Alexander LM, Godwin JR. In the healthcare sector: consolidation accelerated, competition undermined, and patients at risk. University of California, Berkeley. Available at: https://publichealth.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Private-Equity-I-Healthcare-Report-FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2022.