Urgent message: Sore throat and throat pain are common complaints in the urgent care setting. While infectious causes are the most common and the likely cause of the patient’s complaint, it is important to consider other causes.

Linu Samuel, MD

Introduction

Sore throat and throat pain are common chief complaints across all ages in the urgent care setting. As clinicians who likely see these complaints multiple times a day, our differential diagnosis when walking into the patient room probably consists of only the most common causes of pharyngitis, which are the infectious causes (viral pharyngitis, allergic pharyngitis, and streptococcal pharyngitis). While it is easy to consider sore throat and throat pain to be “just pharyngitis” and rely on decision criteria and/or point-of-care testing to make or confirm our diagnosis, it is always important to obtain a thorough history and physical exam, and use our clinical gestalt when the typical infectious history and exam findings are not present. At times, it may be important to revisit the physical exam and ask more questions when history, exam, and our differential do not match. In addition to the viral, allergic, and streptococcal pharyngitis, it is important to remember that a complete differential for pharyngitis also includes gonococcal pharyngitis, infectious mononucleosis, sinusitis, postnasal drainage, herpangina, gastroesophageal reflux disease, smoking, thyroiditis, and foreign body ingestion.1,2

Case Presentation

A 9-year-old female presented to urgent care with the chief complaint of sore throat for the past 2 to 3 hours. She states her throat started to hurt after eating dinner, which consisted of a hamburger, French fries, and corn. She and her parents described the pain as moderate to severe and right-sided. She felt the pain improved minimally after eating yogurt and drinking cold water. The parents did give her Tylenol at the time the pain started, but it had yet to resolve the pain. They described her voice as “hoarse,” but otherwise there were no other symptoms. She denied fever, chills, recent or current URI symptoms, ear pain, drooling, shortness of breath, stridor, chest pain, and abdominal pain. She and her parents denied any recent exposure to strep throat, infectious mononucleosis, or any sick contacts in general. The patient’s medical history and her family history were unremarkable.

Physical Examination

Vital signs were within normal limits and included:

- Temperature: 98.6⁰F

- Respiratory rate: 18

- Heart rate: 97

- Oxygen saturation: 98%

Physical exam revealed the child was well but did have discomfort in the area of her throat/neck. She was active, able to carry a conversation. No obvious stridor was noted. Her oropharynx was unremarkable. There was no erythema, tonsillar swelling, tonsillar exudate, or soft-tissue swelling. Palpation of her neck revealed no enlarged or tender lymph nodes. There was an area of the right anterior neck that with light palpation was able to recreate the patient’s moderate-to-severe sharp throat pain.

At that time, further history was obtained; it was noted the patient’s pain started while eating the hamburger her father cooked on their home grill. At this point the patient was given a combination of Mylanta and viscous lidocaine, and imaging of the neck soft tissue was obtained. Her pain resolved with treatment.

Diagnosis, Course, and Treatment

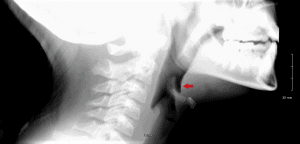

Imaging of the neck (Figure 1) was concerning for a thin linear radiopaque density in the area of the vallecula anterior to the epiglottis. When the imaging results were reviewed with the father and the patient, the father remembered that he had cleaned the grill with a metal bristled brush before cooking. As the patient had a likely foreign body ingestion, with the foreign body most likely a sharp-pointed metallic body, the case was discussed with an ED attending who agreed transfer to the ED for further evaluation and management was advisable.

Figure 1.

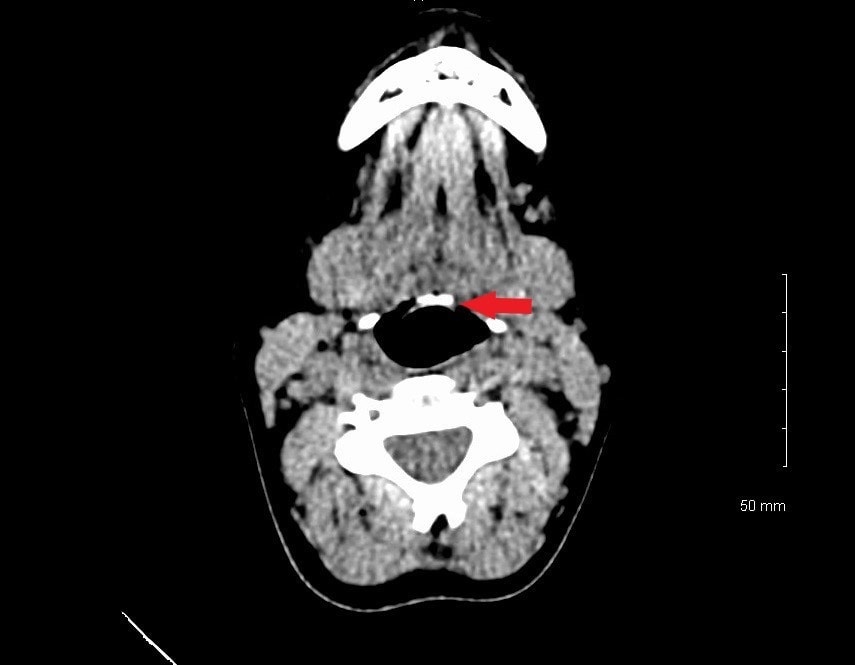

While in the ED the patient had a noncontrast CT of the neck soft tissue, which confirmed there was a linear foreign body anterior to the epiglottis in the area of the vallecula, approximately 9.5 x 1 mm in size (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The patient went to the OR for direct laryngoscopy under general anesthesia. A metallic linear foreign body was found imbedded in the vallecula and was removed. Final diagnosis: metal foreign body of the throat, consistent with metal wire.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Discussion

While there are many more common causes for throat pain, foreign body ingestion should be on a clinician’s differential when the history and physical exam do not point toward the more common causes.

Foreign body ingestion can occur at any age but is more common between the ages of 3 and 6 years and in patients with developmental delay and behavioral problems. While morbidity is low (<1% of all patients), death from foreign body ingestion can occur—and does, in approximately 1,500 deaths a year.3,4 Commonly ingested foreign bodies include coins, button batteries, toys, toy parts, magnets, safety pins, screws, marbles, bones, and large amounts of food.

Foreign body ingestion presentations show great variation between symptomatic and asymptomatic. While approximately 50% of children with witnessed or reported foreign body ingestion are asymptomatic, respiratory distress along with initial suspicion and choking attack while eating have been found to have strong indicators for foreign body aspiration.5 Another study found that 40%–50% of individuals with foreign body ingestion are not witnessed, and in many cases the patient has no symptoms.3 A case series of 325 children with foreign body ingestion found approximately half of the children were symptomatic at the time of ingestion. Those symptoms included retrosternal pain cyanosis, cyanosis, and dysphagia.6

Symptoms of foreign body ingestion are typically dependent on the location of the foreign body. Foreign body in the esophagus may cause refusal to eat, dysphagia, drooling, or respiratory symptoms, or the patient may be asymptomatic. Older children may be able to localize the pain. If the foreign body is in the stomach or intestines, the patient is typically asymptomatic but may have vomiting or refuse to eat. It has also been found that 20%–50% of children with confirmed ingestion are asymptomatic of foreign body ingestion and have possibly been treated for other diagnoses for a month before the diagnosis of foreign body ingestion is made.3,6

With these variations in presentation and symptoms, it is important to have a high index of suspicion for foreign body ingestion when the history and physical exam do not correlate, as seen with our case.

When there is suspicion of foreign body ingestion, plain radiographs of the neck, chest, and abdomen should be obtained. It is important to note that approximately 64% of ingested foreign bodies are radiopaque.6 If radiographs do not reveal a foreign body, advanced imaging can be obtained (depending on patient presentation and the suspected foreign body); this is especially helpful when the suspect body is radiolucent.3,4,7

Management

Management of foreign body ingestion breaks down into two categories—urgent vs expectant management—depending on the location of the foreign body and the specific foreign body. Urgent management, emergency endoscopy, is required if:

- The patient shows symptoms of airway compromise

- There is near to complete esophageal compromise

- The object is sharp, long, or a superabsorbent polymer in the esophagus or stomach

- The object is a high-powered magnet or multiple magnets

- The object is a button battery

- There are signs/symptoms of inflammation or intestinal obstruction such as fever, abdominal pain, or vomiting

Any object in the esophagus for more than 24 hours should be removed emergently so as to decrease the risk of transmural erosion, perforation, or fistula. Patients who do not meet the criteria for urgent management can be observed for 12 to 24 hours, as spontaneous passage is likely.3,4,7

Exceptions to the urgent vs expectant management occur when the foreign body is in the esophagus or the patient is symptomatic and the foreign body is in the stomach or duodenal bulb. Symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain/tenderness. In these situations, urgent endoscopy, within 24 hours, is recommended. In addition, if a foreign body is in the stomach for more than 4 weeks it is unlikely to pass beyond the pylorus and should be removed endoscopically as well.3,4,7,8

Looking specifically at sharp-pointed foreign body ingestion, as with our patient, if there is suspicion of ingestion it is important to determine location of the foreign body. Sharp-pointed objects lodged in the esophagus are at high risk for perforating the esophagus; this is a medical emergency requiring urgent endoscopy for removal. As many ingested sharp objects are radiolucent (eg, fish bones and wooden toothpicks), endoscopy should be performed if there is a high level of suspicion or witnessed ingestion. If the patient is asymptomatic and ingestion is not definite or not recent, CT or other advanced imaging can be considered with subsequent removal or observation and/or close follow-up.7,8

If the sharp-pointed foreign body is in the stomach or proximal duodenum, removal is required due to risk of perforation of the gastrointestinal tract. If the object is found in the small intestine it can be monitored with serial imaging if the patient is asymptomatic. Surgical intervention is required if the object fails to progress after 3 days or if the patient is symptomatic of obstruction or perforation (abdominal pain, fever, vomiting, hematemesis, or melena).3,4,7

With the rising number of foreign body ingestion secondary to the use of wire grill brushes, a high index of suspicion is needed to consider and make the diagnosis of foreign body ingestion in most cases.7,9-11

Citation: Samuel L. A 9-year-old girl with sudden-onset sore throat after a meal. J Urgent Care Med. June 2019. Available at: https://www.jucm.com/a-9-year-old-girl-with-sudden-onset-sore-throat-after-a-meal/.

References

- Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat?. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2912–2918.

- Vincent MT, Celestin N, Hussain AN. Pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(6):1465-1470.

- Dahshan A. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children. J Okla State Med Assoc. 2001;94(6):183-186.

- Uyemura MC. Foreign body ingestion in children. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(2):287-291.

- Haddadi S, Marzban S, Nemati S, et al. Tracheobronchial foreign-bodies in children; a 7-year retrospective study. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;27(5):377-385.

- Arana A, Hauser B, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Vandenplas Y. Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(8):468-472.

- Gilger MA, Jain AK. Foreign bodies of the esophagus and gastrointestinal tract in children. Hoppin AG, ed. Waltham, MA. 2019.

- Kramer RE, Lerner DG, Lin T, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: a clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(4):562-574.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Injures from ingestion of wire bristles from grill-cleaning brushes – Providence, Rhode Island, March 2011-June2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(26):490-492.

- Consumer Reports. Guard against wire grill brush dangers. Available at: https://www.consumerreports.org/food-safety/wire-grill-brush-danger/. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- Aiello C. Mom warns of barbecue danger after son swallows wire brush bristle. Today. Available at: https://www.today.com/health/barbecue-danger-boy-swallows-wire-brush-bristle-lands-er-t113968. Accessed May 13, 2019.

Linu Samuel, MD is a senior staff physician at the Baylor Scott and White Health Convenient Care Clinic – Belton (TX). The author has no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.