Urgent message: Diagnosis of abdominal pain is more complex in women than in men because of the more complex anatomy involved. Using a stepwise approach and involving patients in their care can make a difference.

Introduction

Part 1 of this article [see “Abdominopelvic Pain, Part 1: Approach to Men in the Urgent Care Setting,” at https://www.jucm.com/abdominopelvic-pain-part-1- approach-men-urgent-care-setting/] explained that finding the cause of abdominopelvic pain can be a difficult task for any health-care provider because the diagnostic process is riddled with important decisions. This second part of the article focuses on causes of pain specific to women, and then discusses common pitfalls when evaluating, treating, and discharging patients with abdominal or pelvic complaints. Diagnosis is more complex in women than in men, given the presence of additional organs. It is important to note that pregnancy is discussed here, but the signs, symptoms, causes, and treatment of abdominal pain in pregnancy are beyond the scope of this article. This review focuses on nonpregnancy- related causes of pain.

Consider this case: A 21-year-old woman presents to an urgent care center with a 4-day history of worsening pelvic pain. The pain comes and goes but is worse at night. The patient reports that she has not had vomiting or diarrhea but has had some nausea. She has not taken anything for pain, and she debated going to an emergency department (ED) the preceding night, but the pain subsided. She last had sexual intercourse 2 days before presentation. She says that she has not had vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, or urinary symptoms. Her last menses was 2 weeks before presentation. She used a home pregnancy test when the pain started, and she says the findings were negative. She has no history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). She rates the pain as a 3 on a scale of 1 to 10 but says that it increases to a level of 10 periodically before subsiding. These intense episodes usually last about an hour. She has a temperature of 99.5°F (37.5°C) and a pulse of 101 beats per minute.

This patient presents a wide set of challenges that will require a detailed medical history, a thorough but focused physical examination, and possibly some ancillary testing. What follows is a brief overview of the anatomy specific to women, and then guidance on examination and a discussion of pathology and treatment.

Anatomy

The digestive tract is the same in men and women. The esophagus, the stomach, the small intestines, the large intestines, the rectum, and the anus comprise the passageway for food and liquid moving through the body. The liver, the gallbladder, and the pancreas aid in metabolism and perform other important functions such as detoxifying the blood and controlling blood glucose levels. The urogenital tract is also similar, but women lack a prostate and possess a much shorter urethra, making certain urogenital infections more common. The bladder sits above the musculature of the pelvic floor in the true pelvis, although it is situated higher in men because of the prostate. The descending aorta and the inferior vena cava pass through the abdomino- pelvic cavity. The intraperitoneal organs are the same, but the ovaries, uterus, and adnexa are added to the retroperitoneal lineup. The vagina extends from the vulvar vestibule externally, up and into the body approximately 7.6 cm, seated between the rectum and the urinary bladder. The cervix of the uterus pro-rudes into the upper end of the vaginal canal, leaving a cavity around it in the vagina known as the fornix. The central opening is the os. Just posterior to the vagina internally is an important space for fluid accumulation, the pouch of Douglas, which is between the vagina and the rectum. The adnexa connect the uterus on each side directly to the peritoneal space. At their lateral ends, they broaden to accept oocytes from the ovaries. The uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes are suspended by the broad and suspensory ligaments, which are reflections of the peritoneum. The round and ovarian ligaments are the remains of the gubernaculum, components of embryonic development that also play a suspensory role in regard to the ovaries and uterus.1

Medical History and Physical Examination

The initial assessment of a woman with abdominopelvic pain begins on entry into the examination room. Stability and the need for immediate resuscitation must be addressed. A knowledgeable clinic staff can aide in this process.

Once the patient’s condition is deemed stable, obtaining a thorough medical history is the next step. This can present an uncomfortable, emotional, and sometimes embarrassing challenge for the patient. Consider having the patient’s family or friends leave the room when addressing sensitive topics like sexual history. An in- depth description of the pain should include location, onset, worsening and relieving factors, duration, radiation, character, and severity. Although level and quality of pain do not necessarily correlate with severity of illness, they can give clues to the origin. For instance, patients experiencing ectopic pregnancy may describe sudden and severe pelvic pain. Colicky pain may indicate ovarian torsion, and cramping may indicate dys- menorrhea or spontaneous abortion. Timing related to menstrual cycle and sexual intercourse should be co sidered, because postcoital or mid-cycle pain is indicative of ovarian cyst rupture. Abdominal pain can be the presenting symptom in acute myocardial infarction, more so in women than in men. In fact, up to 33% of women older than 65 years experiencing acute myocardial infarction present with abdominal pain as the chief symptom.2

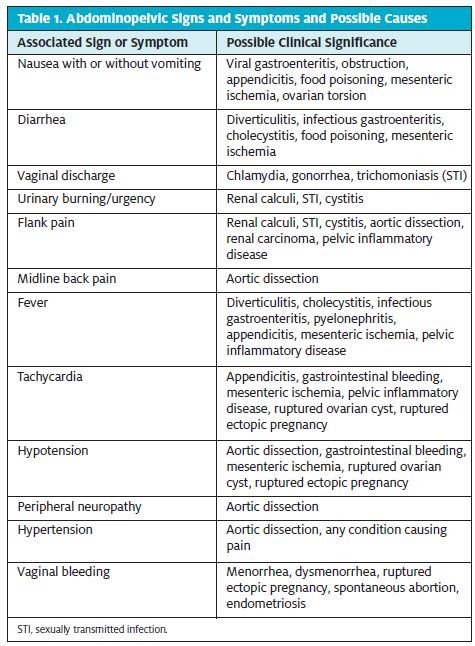

Associated symptoms like fevers, vaginal bleeding, diarrhea, and vomiting should all be documented as well. Table 1 lists associated symptoms and possible etiologies. Note the symptom crossover between gastrointestinal and gynecologic diagnoses.

A full gynecologic and obstetric history is of utmost importance. This should include the date of last menstrual cycle, sexual history and birth control methods, history of STIs, pregnancy and birth history, and history of previous gynecologic problems like polycystic ovarian syndrome or endometriosis. Current pregnancy status or likelihood of current pregnancy should be ascertained, but even patients who say that they are not pregnant should undergo pregnancy testing if they are of childbearing age. The past medical history should high- light risk factors for serious, life-threatening problems. Inquire about history of malignancy, atherosclerotic dis- ease, and previous abdominal surgery. Up to 93% of patients who undergo abdominal surgery, for instance, will develop adhesions that can lead to ectopic pregnancy or spontaneous abortion.3 Some causes of abdominal pain in women can be recurrent as well.

Endometriosis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and ova ian cysts may cause repeated trips to an ED or urgent care center. Even ovarian torsion can be preceded by episodic partial torsion, spontaneous correction, and pain. Note that in this case, the patient had waxing and waning pain for a few days before being evaluated.

After the medical history, the physical examination should be completed in an equally thorough manner. Recall, however, that the examination actually begins when entering the room. Key information can be gathered simply by observing the patient. Is the patient obviously pregnant? Is she diaphoretic? Are there signs of associated vaginal bleeding? The provider’s ability to process information in this brief moment can allow for critical, timely, and potentially life-saving medical decisions. Simply put, is the patient sick or not?

Vital signs are useful but should be interpreted in con- text of the patient’s clinical picture. Free bleeding into the peritoneum can cause reflex bradycardia, and lack of fever can provide misleading reassurance. A car- diopulmonary examination should be done prior to evaluation of the abdomen and pelvis. The presence of adventitious lung sounds, new-onset murmur, or abnormal heart rhythm should send the clinician down a dif- ferent diagnostic pathway and may preclude further evaluation of the lower abdomen or pelvis. The abdominal examination should include standard techniques such as checking for any scars, bruising, or swelling; aus- cultation of bowel sounds; palpation for tenderness, masses, and ascites; and percussion for increased dullness or tympany.

The importance of the routine use of pelvic examina- tion at this point cannot be understated. A full pelvic examination with speculum and bimanual technique should be considered in all women without an obvious nongenitourinary source of pain. The pelvic examina- tion can provide a wealth of information about the reproductive tract. The external genitalia should be evaluated for the presence of ulcers, erythema, and frank discharge from the vaginal canal. A speculum should then be inserted to allow visualization of the vaginal mucosa and the uterine cervix, which may show signs of inflammation and friability if STI is present. Vaginal discharge in the setting of abdominopelvic pain strongly suggests the presence of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Any bleeding from the cervical os should be noted, along with any cervical dilation, and an estimation of blood loss should be made. Once the speculum examination is complete, a bimanual examination using the index and middle fingers on a gloved hand should be performed to investigate for the presence of cervical motion tenderness or uterine, adnexal, or ovarian masses or tenderness. Percussion of the costovertebral angles bilaterally should be performed on all patients with signs or symptoms of UTI to evaluate for renal involvement of the infection or for a potential kidney stone.

Unless there is suspicion for gastrointestinal bleeding, a rectal examination adds no usable information in women.

Diagnostic Testing

There is no standard set of ancillary tests for abdominal pain. A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel can be pursued, but both tests have low potential for reassurance when findings are normal, and they should never be used to rule out serious conditions. For example, only about 36% of patients presenting with acute appendicitis will have an elevated white blood cell count.4

Simple urinalysis is easy to do and can provide valu-ble information when considering urinary infection or calculus. Caution should be taken, however, just as with the complete blood cell count and the comprehensive metabolic panel. Up to 33% of patients with a symptomatic kidney stone will have fewer than 5 red blood cells per high-powered field on microscopy, and in 11%, no red blood cells are visualized.5 Furthermore, up to 33% of patients with appendicitis present with flank pain and urinary symptoms. One in seven may have pyuria on urinalysis, and one in six may have hematuria.6

All women of childbearing age should be questioned about pregnancy. Testing via urine for human chorionic gonadotropin should be considered in patients who will require imaging or whose medical history and age do not rule out pregnancy.

In the setting of vaginal discharge, testing for gono- coccal and chlamydial infections via cervical swab should be accomplished. Fluid sampling for potassium hydroxide and wet-mount evaluation might be consid- ered to evaluate for trichomoniasis, candidal infection, or bacterial vaginosis.

The mainstay of imaging in the woman with a suspected gynecologic problem is transvaginal ultrasonog-aphy. Ultrasonography is less expensive and exposes the patient to less radiation. It is sensitive and specific for the identification of ovarian and uterine masses, ectopic pregnancies, uterine fibroids, ovarian cysts, and end metriomas. Computed tomography is the imaging modality of choice for non-female-specific causes of pain and should be considered a second-line modality in women with questionable genitourinary involvement.7

Diagnosis-Specific Treatment

The following are possible causes of abdominopelvic pain specific to women, along with the typical treatment plans that should be considered.

- Ovarian cyst rupture: Sudden onset of sharp pain, especially mid-cycle in a premenopausal woman, can signal rupture of an ovarian A ruptured cyst can be identified by pelvic ultrasonography and can generally be treated with pain control and rest in the absence of heavy blood loss. A cyst larger than 5 cm is at higher risk for torsion.8 If the patient has signs or symptoms of hypovolemia, sig- nificant bleeding on pelvic examination or ultra- sonography, or signs of infection, then she should be transported to an ED for resuscitation and laparoscopy.

- Ovarian torsion: Torsion can be a complication of a benign ovarian cyst or a complication of ovarian These patients may present with a sud- den onset of severe, low pelvic pain with nausea and vomiting. Diagnosis is confirmed by color flow Doppler ultrasonography. The patients should always be evaluated in an ED once identified, because this is a surgical emergency.

- Ectopic pregnancy: Patients with vaginal bleeding and positive findings on a pregnancy test should be treated presumptively as having an ectopic preg- In the urgent care setting, that means establishing intravenous access, administering fluids, and transporting the patient to an ED via emergency medical services if she is hemodynamically unstable, but transportation by private car can be considered if her condition is stable. In the absence of bleeding or signs of hemodynamic instability, with positive findings on a pregnancy test, it is reasonable to pursue pelvic ultrasonography to differentiate ectopic from intrauterine pregnancy, with the knowledge that this patient will likely need ED evaluation if an ectopic pregnancy is identified.

- Spontaneous or threatened abortion: As with ectopic pregnancy, all patients with vaginal bleeding and positive findings on a pregnancy test should be treated in the ED In the absence of bleeding, if pelvic ultrasonography reveals a threatened abor- tion or a nonviable pregnancy, such as in the case of an empty sac, it may be reasonable to consult with an obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN) and determine a quantitative human chorionic gonado- tropin level rather than refer the patient to an ED. The decision to send a patient for follow-up with an OB-GYN rather than send the patient to an ED should be measured against the risk of complica- tions like infection and the likelihood that the patient will follow discharge instructions.

- Normal pregnancy: Pregnancy can cause abdominal pain in various Women may experience more gastroesophageal reflux disease, changes in bowel habits, and pain related to anatomic changes to the pelvis, commonly referred to as round ligament pain. The urgent care provider should take great care before discharging a pregnant patient with only reassurance. If no positive findings are revealed through the medical history, physical examination, urinalysis, or pelvic ultrasonography, a discussion with an OB-GYN with plans for follow- up should be considered.

Endometriosis: Patients with endometriosis may experience severe acute pelvic pain and dysmenor- In the absence of an endometrioma, or “chocolate cyst,” ultrasonography is not helpful for the diagnosis of endometriosis.9 Pain control and follow-up with an OB-GYN are the mainstays of therapy, but ED evaluation may be warranted if there is no previous history of this diagnosis or if the pain is severe. - PID: The minimum diagnostic criteria for PID includes pelvic pain with one of the following: cer- vical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal Presumptive treatment can be accomplished from the urgent care setting. This includes a single dose of ceftriaxone (250 mg given intramuscularly) and a 14-day course of oral doxy- cycline (100 mg taken twice daily) with or without 14 days of metronidazole (500 mg twice daily).10

- Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: It is impor- tant to ask patients about fertility treatments because of the risk of developing ovarian hyper- stimulation Although it is not common, some fertility treatments may lead to ovarian enlargement, which can cause fluid third-spacing and hypercoagulability. Thus, patients currently undergoing fertility treatment who present with abdominal pain should be transferred to an ED if no obvious nongynecologic cause is identified.

- UTI: UTIs in the absence of urosepsis can be treated with antibiotics from the urgent care setting. If pyelonephritis is suspected, outpatient treatment with a fluoroquinolone or a sulfonamide is still acceptable if the patient is able to keep down fluids and

- Renal calculus: Like UTIs, kidney stones are often seen in the urgent care Routine treatment and discharge home is acceptable, provided that there is no associated infection, that nausea and pain can be controlled with oral medications, and that the patient is able to pass urine. Discussions of stone size and definitive care go beyond the scope of this article. Both kidney stones and pyelonephritis will likely present with costovertebral angle tenderness. Any patient with an infected stone should be sent to an ED for consideration of placement of a nephrostomy tube or ureteral stent, because these patients can become septic quickly

Discharge and Follow-Up Summary

It is not uncommon for a patient to present with confusing symptoms and then for the examination to reveal further ambiguities. As noted repeatedly, abdominal pain is a complex topic, even more so in women than in men.

Sometimes ancillary testing is not helpful either, and the clinician must decide how to handle the patient’s symptoms despite the lack of specific diagnoses.

Consulting a colleague should always be the first step once an impasse is reached. Medicine is increasingly being viewed from a team perspective, and multiple studies have revealed the importance of avoiding hind- sight bias and diagnosis anchoring,11 which is the ten- dency to go along with previous diagnoses without further investigation. A fresh set of eyes, or ears if no other provider is on-site, can help break through these cognitive errors by providing a different set of experi- ences and skills to use in problem-solving.

If multiple heads cannot clearly discern the answer, perhaps sending the patient home with detailed instruc- tions about returning should be considered. This is dis- cussed more fully near the end of this section; however, caution must be taken with patients who appear ill, el- derly patients, patients with significant comorbidities, or patients who do not have adequate transportation to return to the urgent care center if necessary.

If direct follow-up is not an option or the patient is not reliable, consider having ancillary staff members check on the patient via telephone. Patients are some- times reluctant to return for one reason or another. Lack of money, fear, and wishful thinking can all play a part in a patient’s decision-making, and a friendly call from a caring staff member can provide reassurance and open the door to further problem investigation.

If a patient’s diagnosis is in question but she appears ill or has other medical-history factors that make follow-up unlikely, consider transportation to an ED. This decision is not a failure by the clinician but rather a wise and appropriate step in the diagnostic process. The urgent care center is not the ultimate link in the health-care chain. If the decision is made to send the patient home, the importance of solid education cannot be understated. This decision should be based on the patient’s appearance, ability to return, comorbidities that may complicate the problem, and understanding of any instructions given. A 1997 ED study revealed that patients retain only two-thirds of the information given to them at discharge, with specific difficulty remembering information about medications and follow-up. This percentage improved slightly when the provider gave the dis- charge instructions—64% com- pared with 59% when delivered from a nonprovider source.12 This should underscore the critical point that patients dis- charged home need clear instructions, preferably written, with easy-to-follow directions on three key points: when to return to the clinic, when to bypass the clinic and go to an ED, and when improvement should be expected. The clinician should be responsible for delivering these instructions and should consider making plans for contacting the patient at a later date to gauge improvement.

Conclusion

Recall the patient presented in the introduction of this article. Her physical examination revealed mild tenderness bilaterally in the lower abdomen but nothing else. Her medical history was equally nonspecific. A preg- nancy test and simple urinalysis were ordered, and both produced negative findings. Given the lack of specifics, the decision was made to hold off on imaging pending changes in her symptoms. The patient was engaged in her visit and eager to feel better, so she was sent home with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and a detailed plan that discussed possible causes, outcomes, and what to do if the pain got worse. She was also advised to monitor her temperature, to maintain a bland diet, and to increase her fluid intake.

As directed, she returned the next day because of symptoms that had worsened overnight. The decision was made to proceed with outpatient computed tomography (perhaps ultrasonography should have been considered first) of the abdomen and pelvis, which revealed an ovarian cyst of approximately 8 cm on the right ovary. Transvaginal ultrasonography was ordered for better characteriztion, and this revealed a torsed ovary with diminished blood flow. The patient was referred immediately to an ED, where she was evaluated by the OB-GYN surgeon on call. She was taken to surgery, where the torsion was corrected and oophoropexy was performed.

Although initially sent home, this patient was immensely grateful for the thorough evaluation she received at the urgent care center. By simply using a stepwise approach, involving the patient in her own care, and astutely recognizing when imaging was needed, the provider was able to make a difference. With appropriate investigative measures, a good outcome can be achieved.

Citation: Fischer TL. Abdominopelvic pain, part 2: approach to women in the urgent care setting. J Urgent Care Med. October 2016. Available at: https://www.jucm.com/abdominopelvic-pain-part-2-approach-women-urgent-care-setting/.

References

- Morton DA, Foreman KB, Albertine Female reproductive system. In: Morton DA, Foreman K, Albertine KH, eds. The Big Picture: Gross Anatomy. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011 [accessed 2016 March 1]. Available from: http://access medicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=381&Sectionid=40140021

- Lusiani L, Perrone A, Pesavento R, Conte Prevalence, clinical features, and acute course of atypical myocardial infarction. Angiology. 1994;45:49–55.

- Becker JM, Stucchi AF, Reed Abdominal adhesions. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; © 2013 [cited 2016 March 9]. Available from: http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health- topics/digestive-diseases/abdominal-adhesions/pages/facts.aspx

- Lee SL, Ho Acute appendicitis: is there a difference between children and adults? Am J Surg. 2006;72:409–413.

- Bove P, Kaplan D, Dalrymple N, et Reexamining the value of hematuria testing in patients with acute flank pain. J Urol. 1999;162:685–687.

- Tundidor Bermúdez AM, Amado Diéguez JA, Montes de Oca Mastrapa Uro- logical manifestations of acute appendicitis. [Article in Spanish.] Urología General. 2005;58:207–212. Available from: http://aeurologia.com/articulo_prod.php?id_ art=1448705897767

- Benacerraf BR, Abuhamad AZ, Bromley B, et Consider ultrasound first for imaging the female pelvis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:450–455.

- Houry D, Abbott Ovarian torsion: a fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:156–159.

- Bennett GL, Slywotzky CM, Cantera M, Hecht Unusual manifestations and complications of endometriosis—spectrum of imaging findings: pictorial review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6 suppl):WS34–WS46.

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [updated 2015 June 4; cited 2016 March 18]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ std/tg2015/pid.htm

- Schiff GD, Kim S, Abrams R, et Diagnosing diagnosis errors: lessons from a multi-institutional collaborative project. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation. Concepts and Methodology; vol. 2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005:255–278.

- Crane Patient comprehension of doctor–patient communication on discharge from the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:1–7.