URGENT MESSAGE: Although the Affordable Care Act has made some progress in reducing the number of Americans without any health insurance, many of the newly insured are still unable to afford routine healthcare due to plan designs that include high deductibles, copays and coinsurance.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc is Practice Management Editor of JUCM—The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine, a former member of the Board of Directors of the Urgent Care Association of America, and Vice President of Strategic Initiatives for Practice Velocity.

The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA, or “Obamacare”) was intended to herald the first serious attempt to significantly reduce the number of Americans who had no form of health insurance—and the early numbers reflect that it has done just that. A recent Gallup Poll reveals the portion of uninsured Americans has dropped from 18% in 2013 to 11.9% as of December 2015. That translates into nearly 19 million men, women, and children (including adults and children newly eligible for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program) that now have healthcare coverage after being completely uninsured. Not insignificant progress.

With 19 million people who may have been inclined to hold off seeking medical care until a condition became unmanageable now with insurance, one could reasonably predict a boom in new business for urgent care and other providers of medical services. But that hasn’t happened, and the principal reason is that being uninsured and being underinsured by a health policy with high deductibles and coinsurance percentages have roughly the same net effect on a family’s or individual’s finances.

Uninsured vs Underinsured—Is There a Difference?

Generally speaking, an underinsured person is one who is insured but whose out-of-pocket expense for healthcare puts them at significant financial risk. Out-of-pocket costs include insurance premiums, copayments, coinsurance payments, satisfying deductibles, and exceeding defined benefits.

The purpose of any “insurance” should be to protect people from unexpected expenditures that could wipe out their savings and/or limit their ability to seek needed treatment for a major health complaint. With this concept in mind, the “new” insurance plans come with high deductibles, copays and/or coinsurance to keep premiums “affordable” by shifting the cost of routine care to patients. The idea is that when patients pay a portion of the bills themselves, they’ll educate themselves on costs and services, choosing more judicially from among their healthcare options. On the “Obamacare exchange,” the average deductible in a basic, “Bronze level” plan is thus over $5,000 for an individual/$10,000 per family, and even individuals with employer-paid insurance are seeing deductibles ranging from $1,000 to $2,500+ for an individual, twice that for family coverage.

The dilemma that the underinsured finds themselves in is easy to understand. Just like automobile liability insurance, health insurance is now required by law. It’s an additional expense to an already stretched budget, with no option but to pay the premiums or pay a hefty penalty for not having coverage.

Not surprisingly, these previously uninsured persons tend to opt for the least expensive health coverage available. That translates into high deductibles and coinsurance requirements, making the policy too expensive to use except when conditions become unmanageable—just like they did when they were uninsured.

How Many Underinsured Americans Are There?

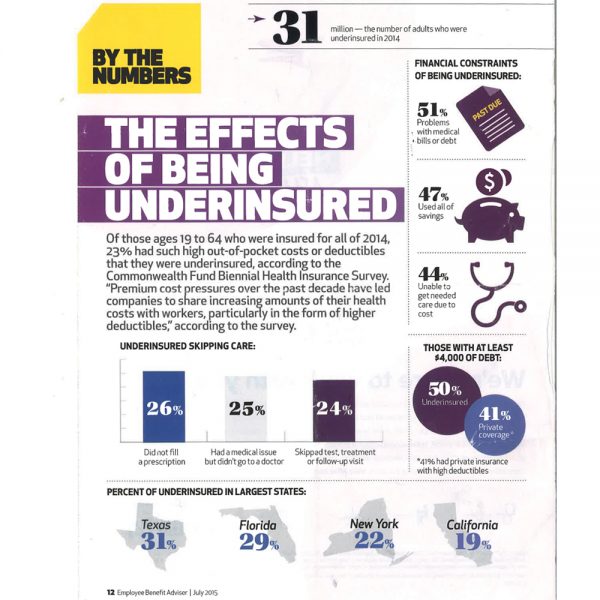

How many underinsured are there? Hard numbers will not be available until after the next census. However, surveys and studies conducted by credible, nonpartisan organizations peg the number at 23% of the insured population, or roughly 64 million people.

Ostensibly, that means 2 out of every 10 insured persons will avoid seeking healthcare unless absolutely necessary. This results in people repeating the precise behavior that the ACA was specifically designed to curb.

For example:

• 26% of underinsured persons have not filled a prescription

• 25% had a medical issue but did not seek care from a physician

• 24% have skipped a prescribed test or failed to show at a follow-up appointment

• 47% have exhausted their personal savings due, at least in part, to out-of-pocket healthcare expenses

• 51% have problems with medical bills or debt

Make no mistake; the Affordable Care Act did not create the underinsured problem, although it has contributed to the issue by converting some people from uninsured (or even adequately insured) to underinsured.

Over 60% of Americans access health insurance through their employers. Over the past decade, skyrocketing health insurance costs and the pressures of a sluggish economy have forced employers to cut their group insurance costs by increasing their plan’s deductible and requiring higher premium participation from employees. The average premium on an employer-provided plan is now $17,575 for families and $8,167 for individuals, with employees contributing $4,955 and $2,173, respectively, toward that amount, according to the 2015 Employer Health Benefits Report by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. That’s just the premium; in addition, greater than 80% of employer-paid plans now have a deductible (up to 95% in the private sector) averaging $1,318 for individuals and roughly twice that for families.

These costs have been especially difficult for lower paid employees, as the additional expense represents a higher total percentage of their income than their better paid colleagues. Many are paying more for less and have effectively become underinsured.

Healthcare in Transition, or Healthcare in Meltdown?

The national objective is to have all Americans covered for essential health services by affordable health insurance policies (rather than by single-payer, socialized medicine). The hopes are that the population will become healthier as access to primary healthcare providers and wellness care becomes a reality for a more significant portion of the populace—noble intentions, but the results to date are mixed, to say the least.

The ACA does more than create marketplaces to purchase health insurance; it has significantly changed the health insurance industry and, to an extent, how healthcare is delivered.

These changes have disrupted the status quo (and many would argue it seriously needed disruption), and in doing so has brought confusion to both the consumer and medical care providers.

For example:

• One of the biggest reforms involved providing health insurance to persons with preexisting conditions. This is great news for people who couldn’t get coverage at any price, but created an actuarial nightmare for the insurance companies. What the insurance companies should actually be charging probably will not be sorted out for at least a couple of years.

• Insurance policies were always difficult to comprehend, but the reforms have taken that problem to a new level. Some essential services, regardless of the plan, are covered 100% by insurance. Services outside those “essential services” may be subject to exceptionally high deductibles, meaning out-of-pocket expenses may place the consumer at financial risk.

• Consumers are only slightly less informed about their policy than the doctors who provide the care. Uncertainty about what terms apply to the plan makes it difficult to collect any fees due from the patient. Often the patient is undercharged because the expense is declined by the insurance company, putting doctors in the collection business.

• Compliance with insurance reform regulations is burdensome and expensive for medical providers. Many smaller practices are selling or joining larger networks who have better administrative resources.

• Then there is the “affordable” part of the ACA. The policies, while similar or identical, may cost different consumers different amounts based on their income…sometimes. The plan offers two subsidies for persons who earn 100% to 400% of the federal poverty guidelines. These subsidies are used to reduce the premium costs. However, if you live in one of the 27 states that have not accepted the federal plan to expand Medicaid, you will only be eligible for a single subsidy. Couple this premium manipulation with the uncertainty of what you will owe at the doctor’s office and you have a situation of not knowing if you can afford the coverage until you use it.

• There are some big winners, particularly in the states that have expanded Medicaid. More of the very poor will be eligible for coverage that limits their out-of-pocket expense to 6% of their income. The bad news is that Medicaid pays doctors less than Medicare, which is already a discounted rate, and few doctors can afford to take on new low rate Medicaid patients. In many states, urgent care cannot survive at Medicaid reimbursement, meaning the only “on-demand” option for Medicaid populations is the emergency room, which is bursting at the seams with patients who could otherwise could be treated in a lower acuity, lower cost setting.

Effect of the Underinsured on Urgent Care

From the standpoint that urgent care offers an on-demand treatment option for nonemergent conditions that’s less expensive than hospital emergency rooms, urgent care could benefit from more “educated” consumers who understand exactly how much it costs and when it’s appropriate to go to primary care; a retail clinic like those in supermarkets, drugstores, and big box retailers; an urgent care center; or to the hospital emergency room. Urgent care offers an important “mid-acuity plank” in a community’s healthcare needs.

However, from the standpoint that Americans continue to struggle economically and many live paycheck-to-paycheck, high deductibles, copays, and coinsurance result in people choosing to forego care or self-treating with over-the-counter medications rather than paying for a physician visit. The risk is that a minor illness evolves into something more serious and more costly to treat. The danger of underinsured consumers could be a decrease in the total number of patients seeking urgent care, which is exactly the opposite of what was intended by expanding insurance coverage.

The lesson for urgent care is that centers need to understand what each underinsured patient will owe at the time of service and collect that money prior to treating the patient. Failing to do so can result in extended accounts receivable days and heavy write-offs of consumer receivables due to denied insurance claims. Processes like real-time eligibility (providing online verification of a patient’s deductible and copay) and credit card preauthorization (automatically charging any patient balances after an insurance claim is adjudicated) integrated with a center’s practice management system can facilitate better communication with patients at time of service and assure a center gets paid in a timely manner for the services it provides.

Conclusion

Clearly, the ACA needs some changes. As it stands, consumers really won’t know if they are “underinsured” until they actually use their policy for something other than a checkup. Physicians are going to have to find ways to be more efficient in delivering care to counter increased costs and reduced insurance reimbursements. This serious national healthcare problem needs intelligent, informed, nonpartisan attention now if it is to achieve its admirable objectives.

Source: Employee Benefit Adviser. July 2015