Download the PDF: Are Urgent Care Providers Liable if They Don’t Test Patients for COVID?

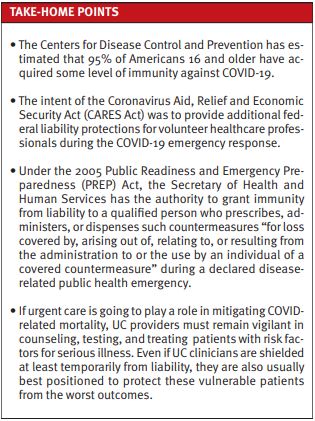

Urgent message: As the severity of newer strains of SARS-CoV-2 has decreased, many patients and providers have become less vigilant about COVID-19. Yet COVID-19 remains among the top 10 causes of death in the U.S. Failure to diagnose and, if eligible, treat patients with COVID-19 may result in significant harm. Professional liability is less likely, however, given the current governmental protections in place.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc is President of Experity Consulting and is Senior Editor of The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine.

Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic brought about changes in how we live our lives. This included times of uncertainty, modified daily routines, financial stress, and social isolation. Today in urgent care centers, visits by patients with a COVID test (symptomatic patients) or diagnosis makes up less than 33% of visits, which is a decrease from roughly 2/3 in 2020.1 Nonetheless, with these numbers, it’s likely that patients may present to UC initially with what and ultimately fatal COVID-19 infection.2

URGENT CARE PROVIDERS GROWING COMPLACENT WITH COVID TESTING

Anecdotally, on the Urgent Care Association listserv, many provider discuss a rising complacency among patients and other UC providers surrounding COVID testing and/or prescription of potentially indicated antiviral medications.

This falls under the umbrella of what might be termed “pandemic apathy.”3 The virus has now evolved into a less virulent form, and COVID vaccines are readily available. Add to this the fact that many of the of COVID-positive patients that urgent care professionals see—including those with risk factors for serious illness—look less sick than the patients with influenza. Another factor is that people can get free at-home kits from the government and very inexpensive test kits from any pharmacy. Every U.S. household is eligible to order four free at-home COVID-19 tests.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated that 95% of Americans 16 and older have acquired some level of immunity against the virus.5 Thus, the question that arises is, what is the medical malpractice liability risk by not performing a COVID test if indicated?

DISCUSSION

Urgent care owners and operators may question their providers’ duty when they know a patient is symptomatic.6 First, on March 27, 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) was signed into law. The legislation provides additional federal liability protections for volunteer healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 emergency response.7

While the CARES Act provision only protects volunteers, another provision for treatment offered to COVID-19 patients is found in the 2005 Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act.8 This law grants authority to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to provide that a “covered person,” including a qualified person who prescribes, administers, or dispenses “pandemic countermeasures,” “shall be immune from suit and liability under Federal and State law with respect to all claims for loss covered by, arising out of, relating to, or resulting from the administration to or the use by an individual of a covered countermeasure” during a declared disease-related public health emergency.9

With that in mind, multiple states have followed suit and enacted similar laws to protect healthcare providers.10,11 For example, under Michigan law, a physician would not have a traditional physician-patient relationship based on ordering or conducting a screening test. There is no explicit or implicit contractual arrangement for performing COVID-19 testing, for example.12

The “Limited Physician-Patient Relationship”

The Michigan Supreme Court looks to have created what it terms a “limited physician-patient relationship” in Dyer v Trachtman.13 While that case concerned an independent medical examination (IME) where the examining physician aggravated the plaintiff’s injury, the Supreme Court found that:

“…an IME physician has a limited physician-patient relationship with the examinee that gives rise to limited duties to exercise professional care.…The limited relationship imposes fewer duties on the examining physician than does a traditional physician-patient relationship. But it still requires that the examiner conduct the examination in such a way as not to cause harm.”13

And in Paul v Glendale Neurological Associates, P.C.,14 the Michigan Court of Appeals, citing Dyer, held that “…this duty does not constitute a duty to diagnose or treat an examinee’s medical conditions.”14 And while lab testing is quite distinguishable from an IME, it is difficult to contemplate a sufficient factual scenario to satisfy the elements of the medical liability standard. In that case, another state statute also provides protection for local public health officials.15

In Michigan, doctors have benefit from this precedent and the qualified immunity it creates under state law. A patient would be required to show gross negligence to overcome the immunity. This would be nearly impossible in the testing context.16 Again, under Michigan law, a physician:

“…is not liable for an injury sustained by a person by reason of those services, regardless of how or under what circumstances or by what cause those injuries are sustained. The immunity granted by this subsection does not apply in the event of an act or omission that is willful or gross negligence. If a civil action for malpractice is filed alleging an act or omission that is willful or gross negligence resulting in injuries, the services rendered that resulted in those injuries shall be judged according to the standards required of persons licensed in this state to perform those services.”17

Other states have enacted similar legislation and governors have signed executive orders seeking additional protections. In Virginia, for instance, a state statute applicable to “disasters” provides liability protection to healthcare providers during state or local emergencies, where the exigencies of the emergency “render[] the health care provider unable to provide the level or manner of care that otherwise would have been required in the absence of the emergency….”18 Similar to Michigan’s law, immunity is not applicable to cases involving gross negligence or willful misconduct.

In Tennessee, the governor is empowered to declare through Executive Order “limited liability protection to healthcare providers, including hospitals and community mental health centers” providing care to “victims” of an emergency.19 Likewise, the protection immunity is inapplicable to claims found to involve gross negligence or willful misconduct.19

In Texas, a person who in good faith administers emergency care is not liable for civil damages for an act performed during the emergency, unless the act is willfully or wantonly negligent. However, this law does not apply to care administered for or in expectation of remuneration. 20

Maryland Public Safety § 14-3A-06 states that “[a] health care provider is immune from civil or criminal liability if the health care provider acts in good faith and under a catastrophic health emergency proclamation.”21

Kentucky provides civil immunity for care provided to a COVID-19 patient.22 The law, signed into law on March 30, 2020, states:

“A health care provider who in good faith renders care or treatment of a COVID-19 patient during the state of emergency shall have a defense to civil liability for ordinary negligence for any personal injury resulting from said care or treatment, or from any act or failure to act in providing or arranging further medical treatment, if the health care provider acts as an ordinary, reasonable, and prudent health care provider would have acted under the same or similar circumstances.22“

Finally, Connecticut Executive Order No. 7U states:

“[I]n order to encourage maximum participation in efforts to expeditiously expand Connecticut’s health care workforce and facilities capacity, there exists a compelling state interest in affording such professionals and facilities protection against liability for good faith actions taken in the course of their significant efforts to assist in the state’s response to the current public health and civil preparedness emergency.23“

It is clear that multiple states and the federal government have contemplated possible liability for the care of patients infected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Deciding whether to test or not test can be added by analogy if not specific statutory language.

What About Prescribing Antivirals?

Many proposed treatments have been put forth as potential therapies to limit COVID related morbidity and mortality over the past 3 years. Currently, the most promising option for outpatient treatment of patients at risk for serious disease is nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid). Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir is a combination of two prescription antivirals which have been shown to reduce the risk of hospitalization and death among outpatients with COVID-19 infection.24 In November 2022, the CDC reported on a real-world study that showed adults at high risk of serious outcomes who took nirmatrelvir/ritonavir within 5 days of a COVID-19 onset had an 88% lower rate of hospitalization or death than those who were not given the drug.25 The drug has been authorized for emergency use by the FDA under an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in outpatients patients aged 12 and older with positive results of direct SARS-CoV-2 viral testing, and who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death.25

However, the results of a 109,000-patient study may renew questions about the U.S. government’s use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, “which has become the go-to treatment for COVID-19 due to its at-home convenience.”26 Israeli researchers found that nirmatrelvir/ritonavir reduced hospitalizations among people 65 and older by roughly 75% when given shortly after infection, which is consistent with earlier results used to authorize the drug in the U.S. and other nations.27 However, people between the ages of 40 and 65 saw no measurable benefit, according to the analysis of medical records.28

CONCLUSION

The pandemic created extraordinary conditions, and most laws and regulations reflect an attempt to provide healthcare professionals with a great deal of insulation from lawsuits when they demonstrate good faith efforts and reasonable care in their decisions to treat COVID-19.

A provider, weighing all factors, may point to this evidence as well as limitations in the urgent care delivery model, such as the absence of renal function testing, as reasons not to prescribe nirmatrelvir/ritonavir to qualifying patients. Additionally, a provider would be required to review hundreds of potential medication interactions, which can also be quite time consuming. These factors provide enough disincentive to obviate some UC clinicians from even considering antiviral prescribing in their practice.

However, COVID-19 remains a leading cause of mortality and certainly the primary condition with significant risk of short-term mortality for which patients are likely to present initially to urgent care.

If UC is going to play a role in mitigating COVID-related mortality, it is incumbent upon UC providers to remain vigilant in counseling, testing, and treatment among patients with risk factors for serious illness. Even if UC clinicians are shielded (temporarily at least) from liability, they are also usually best positioned to protect these vulnerable patients from the worst of possible outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Experity. Urgent Care Visit Volume Stabilizes with Decrease in Flu Visits. Updated January 27, 2023. Available at: https://www.experityhealth.com/urgent-care-visit-data/. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Cheney C. Coronavirus pandemic resulted in unprecedented urgent care utilization changes, study finds. Health Leaders. Available at: https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/clinical-care/coronavirus-pandemic-resulted-unprecedented-urgent-care-utilization-changes-study. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Rothman L. It’s harder than ever to care about anything. Time. April 13, 2022. Available at: https://time.com/6160337/hard-to-care-about-anything/. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Get free at-home COVID-19 tests this winter. Covid.gov. Available at: https://www.covid.gov/tests. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Goodman B, Cohen E. CDC ends recommendations for social distancing and quarantine for Covid-19 control, no longer recommends test-to-stay in schools. CNN. Updated August 11, 2022. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/11/health/cdc-covid-guidance-update/index.html. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Parisi SG. COVID-19: the wrong target for healthcare liability claims. Leg Med. September 2020. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7229443/. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- H.R.748 – CARES Act, 116th Congress (2019-2020). Available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/748/text?s=2&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22hr748%22%5D%7D. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- 42 U.S.C. § 247d-6d.

- Wellford B. Health care provider liability during the covid-19 pandemic: ways to ensure protection. Baker Donelson. April 7, 2020. Available at https://www.bakerdonelson.com/health-care-provider-liability-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-ways-to-ensure-protection. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- American Medical Association. Liability protections for health care professionals during COVID-19. Updated April 8, 2020. Available at https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/sustainability/liability-protections-health-care-professionals-during-covid-19. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- New York State. Senate Bill 5177. Available at: https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S5177. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Jacobson PD. Physician liability for COVID-19 testing. Network for Public Health Law. August 14, 2020. Available at https://www.networkforphl.org/resources/physician-liability-for-covid-19-testing/. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Dyer v Trachtman. 470 Mich. 45, 49, 679 N.W.2d 311, 314 (2004).

- Paul v Glendale Neurological Assocs. PC, 304 Mich. App. 357, 366, 848 N.W.2d 400, 405 (2014), citing Dyer, supra at 51.

- MCL 333.2465(2).

- Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act, May 19, 2020. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/prep-act-advisory-opinion-hhs-ogc.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- MCL 30.411(4).

- Va. Code § 8.01-225.02.

- Tenn. Code § 58-2-107(l)(2).

- Tex. Code § 74.151.

- Maryland Courts and Judicial Proceedings § 5-603.

- State of Kentucky. Senate Bill 150. Available at: https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/bill/20RS/sb150/bill.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- State of Connecticut. Executive Order. Available at: https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/Office-of-the-Governor/Executive-Orders/Lamont-Executive-Orders/Executive-Order-No-7U.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Reis S, Metzendorf MI, Kuehn R, et al. Nirmatrelvir combined with ritonavir for preventing and treating COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;9(9):CD015395.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA updates on Paxlovid for health care providers. Available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-updates-paxlovid-health-care-providers. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Parisi SG. COVID-19: the wrong target for healthcare liability claims. Leg Med. September 2020. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7229443/. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Linnane C. Study finds Pfizer’s antiviral has little or even zero benefit for younger adults, and WHO says BA.5 omicron subvariant accounted for 74% of cases in latest week. Market Watch. Available at https://www.marketwatch.com/story/study-finds-pfizers-antiviral-has-little-or-zero-benefit-for-younger-adults-and-who-says-ba-5-omicron-subvariant-accounted-for-74-of-cases-in-latest-week-11661438030. Accessed March 30, 2023.

- Perrone M. Study: Pfizer COVID pill showed no benefit in younger adults. Associated Press. August 24, 2022. Available at https://apnews.com/article/covid-science-health-seniors-d8f6af66517054aae7fb27d1ecc6df66. Accessed March 30, 2023.