Published on

Urgent message: Lacerations are a common reason for patients to present to urgent care. Data suggest not all providers are comfortable managing lacerations, however. Clinicians who need additional training should be afforded such in order to reduce acuity degradation and unnecessary referrals to the emergency room.

David T. Ford, MD; Patrick M. O’Malley, MD; and Brantley Dick, MD

Citation: Ford DT, O’Malley PM, Dick B. Assessing Urgent Care Clinics’ Readiness to manage a lip laceration. J Urgent Care Med. 2023;17(8):39-41.

Key words: urgent care, laceration, research

ABSTRACT

Acuity degradation—generally, the practice of referring patients who theoretically could be treated in an urgent care center to an emergency room or other setting due to on-site providers’ inexperience or discomfort with performing a given procedure—is a growing concern in the urgent care industry. A telephone survey was devised to assess how common it would be for an urgent care center to suggest an alternate setting to a “patient” who called to inquire about being seen for a lip laceration.

INTRODUCTION

It is common for patients to present to an urgent care clinic for assessment and treatment of lacerations. However, not all urgent care providers are comfortable managing lacerations, and patients are subsequently sent to an emergency room for repair.

A speaker at a national urgent care conference brought this issue to light when he called an urgent care center live, from the lectern, and asked if they could repair his simple laceration; he was told that they could not, and that he would “need to go to the ED.”

The issue of acuity degradation is an important one that needs to be addressed. It is felt by many in the urgent care world that UC clinicians should be expected to handle straightforward lacerations.1

One possible reason could be a pragmatic one: consider that flat-fee reimbursement may lead UC operators to refer procedures that take time and require costly medical products/devices to manage them.2

However, the inability or declination to manage simple lacerations has several ramifications. When a patient presents with a simple laceration and is told that the UC clinician is unable to address their need, there is a loss of revenue, patient confidence in the clinician, and a decrease in the chance that they will return to that UCC in the future.

Over time, many UCCs have become staffed by some clinicians with less training in procedural skills. Whereas physicians who go through a residency program are required to develop a high level of procedural skills, other providers may be less likely to have the same level of training and experience. This can include both advanced-practice providers and some physicians who may not have had much experience managing lacerations during their training, as well.

When UCCs refer patients with relatively simple lacerations to the ED, this ties up staff and resources that could have been devoted to patients with truly emergent complaints. There is also a strong economic factor, as the cost of managing a laceration in the ED is higher than in a UCC.3

This survey was developed to further evaluate how frequently a hypothetical patient with a laceration would be redirected to another setting, such as an ED.

METHODS

A list of UCCs in every state was obtained, with two clinics from each state randomly chosen and combined into a master list. Three physicians called each of these clinics, posing as a theoretical patient with a lip laceration, and followed a standard script: “Hi, my name is Sam. I cut my face on a door frame. I have a 1 inch cut to my upper lip and skin. Is this something that you can repair there?”

Calls were placed several hours prior to closing to ensure that impending close of day was not a factor in any decision. If the provided phone number was incorrect or disconnected, another clinic was found randomly in the database, to ensure that 100 clinics, two from each state, were contacted in order to provide a good representation of trends across the country.

If “Sam” was told that the a given UCC could treat his laceration, he simply replied, “Thank you” and ended the conversation. If the answer was “No,” he would ask if they were able to repair lacerations in general, with the hopes of gathering any additional details as to that UCC’s ability in this capacity. The researcher posing as Sam also inquired about where he should go for this laceration repair. Some UCCs answered “Maybe” to the subject question, explaining that the clinician on-site would have to evaluate the wound before making a determination, so this was included as an option. Answers and free-text information were entered into a spreadsheet for analysis.

RESULTS

Of the 100 clinics that were contacted and provided with the scenario described, 38 (38%) told our mock patient “Yes,” they could handle the laceration. Seventeen clinics (17%) answered “Maybe,” and 45 (45%) of the clinics said “No”.

Of the 45 UCCs that said they would not do the repair, four said they do not manage lacerations at all; 42 told the mock patient to go to the ED; and two provided the name of another UCC or ED. One provided the name of another urgent care only.

DISCUSSION AND LIMITATIONS

One of the limitations of our study was that we did inquire on any policies that a given UCC had on whether a provider was allowed to repair facial lacerations, ahead of time. We also did not break down the UCCs with regard to how many were staffed by physicians vs advanced-practice providers, or a mix of physicians and APPs.

We chose a lip laceration for our mock patient’s injury as this would raise the possibility of cosmetic concern and perceived complexity because of involvement of the vermillion border of the lip. The results show that nearly half of surveyed UCCs do not feel comfortable managing what is felt by most to be a simple laceration on the face.

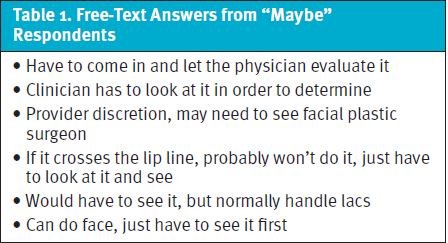

The free text/additional responses warrant deeper evaluation. As it is understood that the person answering the phone cannot see the injury and may not be in a clinical position, the answer was frequently expanded with them stating, “It depends, the clinician must evaluate it first in order to decide” or something similar to this. Seventeen percent of surveyed UCCs answered in this way, which the authors feel is a very reasonable response in the sense that they are at least willing to evaluate the injury in order to make a decision. See Table 1 for more detail.

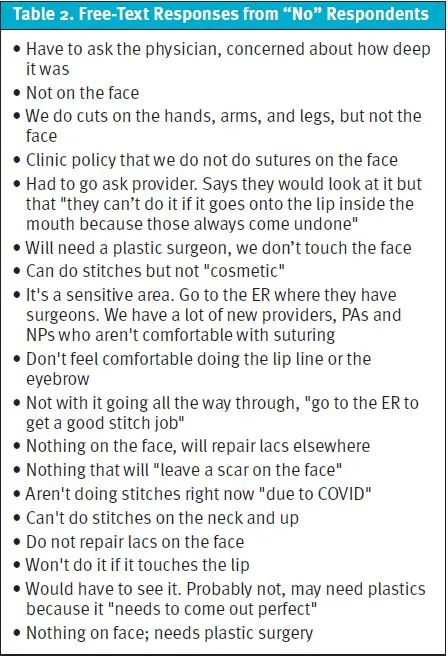

For the clinics that said “no” the reasons given were varied, and our mock patient tried to get further statements and justifications. See Table 2 for a list of responses provided.

It is interesting to note that many who said “no” answered this way because they felt closure required plastic surgery in the ED—likely unaware that getting a plastic surgeon to come to the emergency department to repair a simple laceration is not likely to happen, and that such a wound will be managed by an emergency physician, PA, or NP. Also, it is often unnecessary and not beneficial to have simple lacerations repaired by a plastic surgeon as this often offers no patient satisfaction benefit but does increase ED length of stay.

It should be noted that clinic staff who answered the call may not have been clinical staff, and the clinician on duty may not have been asked directly. As such, if a clinic can handle lacerations it is imperative that this vital information be passed along to those who answer the phones so patients receive accurate information. An interesting follow-up study would consist of calling these same clinics and speaking directly to the clinician on duty to see if there is a disconnect between what the clinician can do and the information that the staff answering the phone provide.

This study raises several important questions. Should UCCs be able to handle lacerations like this? If so, why does it appear from our limited survey that so many patients are being referred away? Is it lack of communication between clinicians and staff answering the phone? Should protocols be devised whereby patient calls should be transferred directly to the UC clinician? Is it lack of training, education, and comfort level of clinicians?

Anecdotal experience of the authors brings to light the possibility that front-office staff answering the phones may not actually be asking the clinician if they can, in fact, manage a particular patient.

For example, the ED clinician may call the urgent care center to discuss a patient who was referred by urgent care, with the urgent care clinician unaware that the patient was referred away. While they may voice frustration with this, the situation could have been avoided had there been better lines of internal communication.

Urgent care clinicians should be expected to manage most lacerations on ambulatory patients. Not doing so puts an undue burden on emergency departments that are already overwhelmed. UCCs should identify clinicians who need help with this basic skill set and then fill that knowledge and skill gap.

The biggest burden is on the patients, who likely will experience much longer wait times and incur much higher charges in the ED. We estimate that this happens tens, if not hundreds of times a day in urgent care centers across the country. It is not known, and it was not asked, whether or not the patient would be charged for having the patient come in and allowing the clinician to evaluate and make an assessment. This would serve as an interesting follow-up study.

REFERENCES

- Murphy R. Increase clinic revenue by avoiding acuity degradation. SolvHealth. Available at: https://www.solvhealth.com/for-providers/blog/increase-revenue-by-avoiding-acuity-degradation. Accessed March 29, 2023.

- Experity. Just checking in: episode 33—reimbursement trends in urgent care. Available at: https://www.experityhealth.com/blog/just-checking-episode-33-reimbursement-trends-urgent-care/ . Accessed March 29, 2023.

- CostHelper Health. How much do stitches cost? Available at: https://health.costhelper.com/stitches.html. Accessed March 29, 2023.

Manuscript submitted August 12, 2022; accepted October 17, 2022.

Author affiliations: David T. Ford, MD, Emergency Medicine, Prisma Health Richland/University of South Carolina School of Medicine-Department of Emergency Medicine. Patrick M. O’Malley, MD, Emergency Medicine, Newberry County Memorial Hospital. Brantley Dick, MD, Emergency Medicine, Prisma Health Richland/University of South Carolina School of Medicine-Department of Emergency Medicine.

Download the PDF: Assessing Urgent Care Clinics’ Readiness to Manage a Lip Laceration