Published on

There are some diagnoses that will be missed by nine out of 10 physicians; this is one of them. However, our goal is not to meet “Standard of Care” but to provide excellence in care:

- Take every patient at face value, without trying to guess their intentions for secondary gain.

- Ensure you are aware of the chief complaint stated to the staff in the urgent care center.

- Be an open book in your impression and plan. You don’t always have to be right, but your reasoning should be clear and appro priate. In the case of diagnostic uncertainty, discuss in a progress note if your thought process cannot be intuited from the chart.

- Discharge instructions should be time- and action- specific.

The Patient’s Story

David Lykins is a devoted father and husband whose wife Jill is 15 weeks pregnant with their fourth child. His career started as a fire- fighter and paramedic; he worked his way up to battalion chief.

David likes to spend as much time as possible with his family. Jill brings the boys to the firehouse every few days and he spends several hours with them.

On Feb. 24, 1999, a 911 call dis- patched the team to the scene of a worker with his leg caught in an auger “wrapped around like a piece of spaghetti.” Though this was a new situation, David took charge and directed everyone, including officers his own rank.

During the 45 minutes it took to extricate the worker, “David talked to me, as I was laying there, waiting to get untrapped. [He] asked me how many kids I had and what my name was and, you know, tried to keep me conscious, and I did stay conscious

…After my accident… I was in the hospital and Mr. Lykins came to the hospital after a run and just checked on me to see how I was doing. I was lucky to be alive and he was glad to see me alive.”

In early March 2000, David has problems of his own.

He has severe left shoulder pain and presents to the emergency department at Shady Valley Hospital.

THE DOCTOR’S VERSION

(The following, as well as other case notes to be included, is the actual documentation of the provider, including any punctuation and spelling errors.)

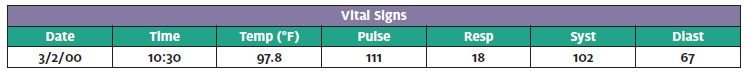

Chief complaint per triage RN (March 2, 2000 at 10:30AM): c/o left shoulder pain … (see below) Arrives via wheel chair (WC).

CHIEF COMPLAINT (physician assistant, Ed Heller) at 10:45:

This is a 42-year-old male who is a fire fighter for Fair- town. He says he was lifting patients yesterday. He complains of left shoulder pain. He says he is unable to move his left arm. He has had no trauma as far as a fall. He has done only lifting. He never had anything like this before. Review of systems is otherwise negative. There is no chest pain, shortness of breath, diarrhea or constipation. No dysuria. No numbness or tingling of the extremities. No peripheral edema.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY:

Allergies: NKDA

Meds: None

PMH: He has a history of abdominal pain two weeks ago. CT scan was done. He does not know the results or what they were looking for. He is vomiting here possi- bly due to the pain that he has.

SH: Unremarkable

FH: Unremarkable

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION:

The patient is alert and oriented. He is somewhat inappropriate as far as pain and physical examination in relation to complaint and history. He refuses to move his arm. He is in an extreme amount of pain when I try to move his arm or touch him whether on his arm or on his clavicle. He has good grip. He is able to extend and flex his elbow and pronate and supinate. He has good distal light touch sensation, pulses and capillary refill.

TESTING (10:55):

Left shoulder and clavicle XR: No fracture of shoulder or clavicle

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT COURSE:

11:05 – Demerol 50mg, Phenergan 25mg IM

12:25 – Phenergan 25mg IM

12:50 – Repeat vitals: Pulse 102, Resp 16, BP 102/65

PROGRESS NOTE (PA Ed Heller):

I talked with Dr. Oster [the primary care doctor] who says the patient tends to sometimes overreact to his health care needs, and it does not surprise him that the gentleman will not move his arm and that his physical examination is not in proportion with his complaint and history.

DIAGNOSIS (12:57):

Left shoulder pain/strain

DISPOSITION:

Rx: Vicodin. Left arm in a sling with instructions to rest with no lifting. Apply ice and return to ED if worse. Soft diet. Dr. Oster will see him in the next two to three days.

ATTENDING NOTE:

(Actual documentation from ED attending physician, Dr. Timothy Vaughn.) This is an attending note to ac- company the dictation by the PA: He is a healthy male firefighter. He apparently has had some left shoulder pain after doing some lifting of patients over the last couple of days. It is very painful with range of motion and any palpation. He has no abdominal pain, chest pain or shortness of breath. Apparently, these symptoms started roughly at the same time. He has had no fever. He has had no skin breaks to that shoulder. He is very uncomfortable with any movement of his shoulder. On palpation, there is no erythema or swelling. His left upper extremity neurovascular examination is intact. The x-rays are normal. The patient is vomiting, and I do not have a good clue as to the cause of this, other than the pain from his shoulder. We have given him Phenergan on two occasions with some improvement. This looks to be more musculoskeletal, and certainly, I see no evidence of any referred pain. This is very joint specific. There is nothing on his examination or in his history that makes me think this is a septic joint.

Ed Heller, PA Timothy Vaughn, DO

(Author’s note: This seems like a straightforward shoulder strain, pain with motion and palpation. But is this the whole story? Let’s first look at patient safety issues with this chart.)

Patient Safety and Risk Management Issues:

Error #1: Not reading nursing notes.

Discussion: Can you decipher the hieroglyphics recorded by the nurse? Neither could the doctor. There was no effort to speak with the nurse to discover what was recorded. When this case ended up in court, her deposition testimony finally revealed the answer: Complaints of left shoulder pain, chills and fever. Not reading the nurses/triage notes is a common theme in medical malpractice cases.

Teaching point: Always read the nurses’ notes. If the notes cannot be understood, speak with the nurse.

Error #2: Poor correlation of mechanism.

Discussion: The patient had been lifting, but when? How soon after the lifting did the pain start? This documentation does not build a case for a reliable mechanism.

Teaching point: Correlate the symptoms with the presumed mechanism.

Error #3: Too narrow of a differential diagnosis.

Discussion: Just because most patients with shoulder pain have a strain, that doesn’t mean they all do. Could shoulder pain in a 42-year- old man be from a pulmonary or cardiac etiology? Absolutely! Questioning as to exertional symptoms, diaphoresis and dyspnea, fever and chills (which was recorded), and cardiac risk factors is advisable. An ECG is a simple and inexpensive screening test, as is a chest x-ray.

Teaching point: Maintain a high index of suspicion for atypical pre- sentations of life-threatening diagnoses—especially when a patient’s pain seems out of proportion to the diagnosis.

Error #4: Including conjecture in the note.

Discussion: Some may make the argument that it is important to note that a “patient tends to sometimes overreact to his health care needs,” but doing so does up the ante. And how does this help with medical decision making? Think of it this way: If the patient actually is over-reacting, it doesn’t help you. And if the patient actually has something bad, it definitely doesn’t help you.

Teaching point: The time for conjecture is on the call, not in the note.

BACK TO THE FUTURE (ONE DAY BEFORE THE EMERGENCY ROOM VISIT):

As it turns out, our patient’s pain actually started the pre- vious day. This is also part of the “ancient Egyptian writ- ing” recorded by the triage nurse: “symptoms started yesterday afternoon.”

David and his wife have a meeting with a lawyer to discuss estate planning matters. As they leave the office David comments that his shoulder is bothering him. Later that night, the pain is stronger and he takes 800 mg of ibuprofen. The next day at 8 a.m., Jill calls their primary care physician, who cannot see him until 11 a.m. David is unable to wait that long, so is referred to urgent care.

THE URGENT CARE RECORD PER DR. BENJAMIN ROTH:

- Triage (9:39AM): Complains of intense pain left shoulder which began yesterday

- History: Pt works for fire dept, was lifting patients, pain started hours after. Has headache, nausea, vom- iting and feels dehydrated. Pt. feels it is not cardiac re- lated but like it’s in the muscle. Pt. iced and took ibuprofen. Unable to move shoulder, had fever all night, couldn’t sleep secondary to the pain.

- PE: Vitals: temp 97.5, pulse 116, resp 16, BP 120/78. Possibly swollen, extremely tender, no redness. ROM is zero. A&O X 3

- Urgent Care course: Vomited in clinic X 1

- Diagnosis: Severe left shoulder pain, needs septic arthritis ruled out

- Doctor note: Discussed with ER at Shady Valley.

Will send him down there for evaluation.

THE ED BOUNCEBACK:

David is discharged from the ED at 12:57 p.m., and his wife drives him to the pharmacy to pick up the prescrip- tion for Vicodin. On the way, they stop for gas. David vomits, then gets out of the car and urinates on the gas pump. When they arrive at home, David goes to bed. Jill can hear him moaning in pain.

His situation worsens over night:

- Midnight: Pain is increasing and David asks for pain medicine.

- 2 a.m.: Asks for more pain medicine.

- 3:30 a.m.: Jill calls the primary care doctor and “on call” who tells her to go back to the ED if worse, or wait until the morning. David says he does not want to return to the ED because they had not done anything for him when he was there.

- 6:30 a.m.: David wants to take a bath before going to the doctor. His wife notices reddening and swelling up David’s arm to the shoulder. It looks like a bruise.

- 8:30 a.m.: David presents to his primary care doctor hyperventilating and acutely ill, appearing with edema over the left shoulder to the nipple and over the sternum medially but “no discol- oration, warmth or erythema. Marked pain with motion of the shoulder.” He is sent immediately to the ED.

ED VISIT #2, MARCH 3, 2000 (ALMOST 22 HOURS AFTER THE INITIAL ED DISCHARGE)

- 10:15 a.m.: Temp 91.3, pulse 61, resp 20, BP 93/80.

The ED team jumps into action.

- 10:25 a.m.: David is seen by Dr. Timothy Vaughn (same doctor as yesterday): “Extremely ill-appearing and much worse than when I had seen him yesterday. Skin on chest is ecchymotic and some areas of necrosis and crepitation are noted underneath. We immediately initiated 2 large bore IVs.”

- 10:40 a.m.: Acute change in vitals: Pulse increases to 145 and SBP drops to 70; David receives IV fluids and dopamine.

- 10:50 a.m.: Blood cultures taken. Started on ticarcillin and clindamycin.

- CBC is normal. Creatinine is 2.5. Elevated liver enzymes.

- Assessment: Extremely critical condition with proba- ble multisystem failure, probably from sepsis second- ary to some underlying myofascial infection.

- Dr. Anderson, general surgeon, is called to the ED to evaluate the patient and observes a discolored, darkened spot about the size of a 50-cent piece; it grows to the size of a softball in a short period of time.

ED diagnosis

- Acute soft tissue infection, left side of chest

- Septic shock

- Multiple organ failure with acute renal and hepatic failure

At 11:30 a.m., David is taken from the ED to a CT scan suite to define extension of the process. Results show necrotizing fasciitis of left anterior chest wall and possibly upper, anterior mediastinum.

HOSPITAL COURSE:

- 12:15 a.m.: From CT, the patient is immediately taken to surgery. Dr. Anderson performs extensive de- bridement of the left anterior chest wall.

- David is found to have acute inflammation of the gall bladder. Further surgery confirms this diagnosis, but also shows right colonic necrosis, which necessitates a right hemicolectomy. This is thought to be from the vasopressors.

- The renal failure worsens, requiring dialysis. David suffers extensive necrosis of the digits of both hands and feet.

- Diagnosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome; David remains on the ventilator.

- David continues a slow, steady, downward spiral. Af- ter a multidisciplinary assessment, it is determined that he does not have a chance of recovering. This is discussed with his family, and comfort measures are taken.

- With his family in attendance, David expires, exactly two weeks after his bounceback visit.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS:

Necrotizing myositis, septic shock, acute respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multisystem organ failure.

Case Discussion

It remains unclear if the emergency room doctor was aware the patient had been to an urgent care previously, or what they wanted “ruled out.” Additionally, it is questionable whether the doctor knew the patient had been having fevers; the nurse’s note was illegible. Both of these issues were prominent in the malpractice case that followed David’s death.

Whether a better outcome would have resulted if an earlier diagnosis was made will never be known. Imagine, however, how differently you might react depend- ing on how this case was presented in one sentence at an M&M conference:

- This is a 42-year-old healthy fireman who was lifting patients, then presented with shoulder pain, worse with Impression: I see this patient every day, 10 times a day: ibuprofen, pain control, sling, discharge.

- This is a 42-year-old healthy fireman who has fever and shoulder pain so severe the range of motion is He was sent from the urgent care to r/o septic arthritis. Impression: Now I’m not so sure…. First, what happened at the gas station? La Belle indifference—an apathetic demeanor observed in patients with necrotizing fasciitis/myositis. He was obviously in the throes of the disease when he walked out of the emergency department. Did the confusion start after he walked out the door, or was it present but unrecognized during the initial ED visit?

Did he “overreact to his healthcare needs,” as he was accused of doing on occasion? We have a 42-year-old career firefighter, a battalion chief with a new complaint of shoulder pain to the point he needs to be brought back to his room in a wheelchair. That would be a serious overreaction. We are taught early in our careers that abdominal pain out of proportion to exam equals mesenteric ischemia. But how about pain out of proportion to our diagnosis in the setting of unexplained vomiting?

Remember the ED doctor’s note: “The patient is vom- iting and I do not have a good clue as to the cause of this, other than the pain from his shoulder.” It is com- mon for orthopedic patients with a broken bone to have nausea and vomiting from pain, but how common is it to have nausea and vomiting from a shoulder strain from lifting?

Necrotizing myositis is extremely rare and difficult to diagnose. However, the classic symptoms were pres- ent: fever, chills, severe pain, vomiting. The problem is these that symptoms are so nonspecific they can be present with the flu, strep throat, or…a simple shoulder strain. So, knowing what we know now, how could this diagnosis have been made?

When presented with clinical symptoms and signs that don’t necessarily fit into our initial impression, we need to dig a little deeper to rule out other causes. He had shoulder pain, but how did history of fever play into the picture?

- We must be vigilant in trying to keep a broad differential, and especially in always considering atypical presentations of life-threatening diseases. The urgent care physician appropriately referred for septic arthritis evaluation. Unfortunately, this information was lost by the ED physician.

- Always read the nurses’ notes. If the ED doc had known of history of fever, maybe this would have prompted an expanded differential.

- Progress notes: Two were done, and well done. There were a lot of data from which to defend this case. (Of course, it’s better if it doesn’t even go to trial in the first place.)

- Be careful about using conjecture in the chart. Even the defense attorney told the jury that use of the word “overreact” was unfortunate. Remember, if the patient actually is overreacting, it doesn’t help you. And if the patient actually has something bad, it definitely hurts you.

- Ensure that protocols exist so records are not discard- ed inappropriately. Pen your initials, date, and time on the records before scanning into the chart.

- Discuss diagnostic uncertainty with the patient and the family so they know when and why to return.

Diagnosis and Management of Necrotizing Fasciitis and Myositis

Necrotizing fasciitis and myositis are deep-seated infections that cause extensive tissue damage and systemic toxicity, and may rapidly progress from an unapparent process to death. Cruelly, it often spares the overlying skin, which makes this diagnosis extremely difficult. The diagnostic gold standard remains surgical exploration.

Definitive treatment involves surgical debridement, along with appropriate antibiotics and hemodynamic sup- portive measures. Unfortunately, even with prompt and optimal treatment, morbidity and mortality of these dis- eases remains extremely high; necrotizing fasciitis has a mortality of 14% to 40%, and necrotizing myositis 80% to 100%, even with appropriate and aggressive treatment. Unexplained pain, as in our case, may be the first man- ifestation of infection.

Making this diagnosis is even more challenging due to the common practice of patients offering alternative explanations for their symptoms, such as the IV drug abuser thought to be “seeking,” the postsurgical patients thought to have pain secondary to weaning off pain medications—or the fireman who has been lifting.

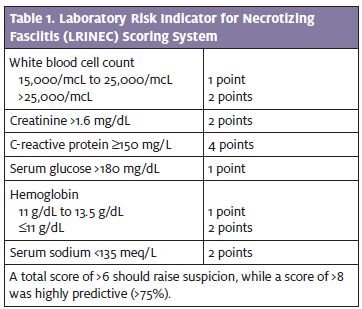

On the flip side is the diabetic with neuropathy who may present with no pain. Skin abrasions, blunt trauma, or overuse injuries may predispose to the development of spontaneous gangrenous myositis, but no etiology is found in over 50% of the cases. The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) scoring system (Table 1) was retrospectively developed for the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis, though this is of questionable utility in the urgent care setting: The components were largely derived from advanced obvious cases, and it is unclear whether it would be consistently reliable in relatively early cases like the one presented here.

Imaging should not delay surgical exploration. Soft tissue x-rays, CT scans, and MRI are most helpful if there is gas in the tissue. A non-contrast CT may be the most expedient test for the presence of air. Gas, though very specific, is not very sensitive. Most imaging shows only soft tissue swelling, which may not be so unusual in the post-traumatic or post-surgical patient.

The take-home point with this case is that necrotizing fasciitis and myositis is a clinical diagnosis which will never be made if it is not in the differential.

Resources and Recommended Reading

- Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, et al. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fascilitis) score: A tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

- Bisno AL, Cockerill FR 3rd, Bermudez CT. The initial outpatient–physician encounter in group a streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(2):607-608.

- Stevens DL. Invasive Group A streptococcus infections. Stevens DL. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(1):2-11.

- Yoder EL, Mendez J, Khatib R. Spontaneous gangrenous myositis induced by Streptococcus pyogenes: Case report and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9(2):382-385.