Urgent message: Urgent care providers have a clinical, legal, and moral obligation to provide appropriate treatment for patients with pain. The first article in a two-part series addresses strategies for managing acute pain.

TRACEY Q. DAVIDOFF, MD

The interpretation of pain by patients is very subjective and not easily measured. That makes management of pain in the urgent care setting difficult. Current pain scales are often inaccurate or not truly reflective of a patient’s real perception of pain, and may reflect other issues or agendas not specifically related to the pain itself. Failure to adequately address pain may result in discomfort for a patient, dissatisfaction with care, and litigation. On the other hand, over treating pain may result in serious morbidity and even mortality for a patient, the potential for addiction or diversion, and litigation for a provider. This is the first in a series of two articles that will address urgent care management of both acute and chronic pain, including strategies for treating pain adequately while simultaneously protecting yourself from dissatisfied patients and litigation.

Introduction

As physicians we have a clinical, legal, and moral obligation to avoid BOTH under prescribing and over prescribing pain medications to our patients. 1 Furthermore we must often make prescribing decisions based on the limited information available to us. Despite recent advances in the understanding of pain control, pain is often left unrecognized and untreated by a fair amount of otherwise excellent clinicians. In 1999 the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) initiated new standards in documentation of patients’ pain and treatment and relief of that pain. In 2001 those standards went into effect, making pain the “5th Vital Sign,” to be recorded with the other standard vital signs. 2 The JCAHO standards also mandated specific training in pain management for all medical students who started training after 2001.

Eleven years later, narcotic addiction – specifically prescription narcotic abuse – is being called the largest epidemic of the 21st century. 3 After aggressively treating pain since 1999 to meet the JCAHO standards, we should not be surprised by this. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), misuse and abuse of prescription pain medications was responsible for more than 450,000 emergency department (ED) visits in 2009, a doubling in just 5 years. More than 1 million ED visits involved the non-medical use of pharmaceuticals. 4

Background

Acute pain and chronic pain are two very different entities and as such, require different evaluation and treatment. Pain is a complex clinical phenomenon that in most cases is a symptom when it occurs acutely, but a disease when it becomes chronic. 5

Acute pain starts abruptly, increases over a short period of time, and can be ongoing or intermittent and recurring. Examples of acute pain, myocardial infarction, gout, etc. By definition, acute pain lasts less than 3 months.

Chronic pain is ongoing more than 3 months and generally due to a non-reversible cause. Examples include metastatic disease, migraines, non-specific low back pain, phantom limb pain, fibromyalgia, and neuralgia. Any pain persisting beyond the usual course of the acute disease or a reasonable time for an injury to heal or associated with a chronic pathologic process that produces pain for months to years can lead to chronic pain. Persistent chronic pain is not generally amenable to routine pain control methods, making it especially hard to treat. Along with the pain comes a whole host of psychological, social, and personal factors that contribute to the difficulty in managing chronic pain.

Addiction refers to psychological dependence on substances for their psychic effects, not their pain relieving effects, and is characterized by a compulsive use despite possible or actual harm. Tolerance is an adaptation to the effects of opioid or other medications administered long term, requiring increasing doses to achieve the initial effect of the drug. This is a natural and expected effect of these substances. Physical dependence is the physiological adaptation of the body to the presence of an opioid medication. Withdrawal occurs when the medication is stopped abruptly. This is also an expected and natural effect of narcotics. Dependence is NOT the same as addiction.

It is our responsibility to assess the quality and severity of pain, identify pain that may represent a medical or surgical emergency, and differentiate acute and chronic pain Furthermore, we need to be vigilant in identifying symptoms that represent withdrawal from narcotics and identify drug-seeking behavior. There is no law stating that a physician is required to treat pain by providing pain medication, specifically narcotics. Pain is a symptom and NOT an emergency medical condition in and of itself. Patients cannot compel a physician to provide medication or treatment that may be detrimental, life-threatening, or to commit malpractice. 6

Quantifying Pain

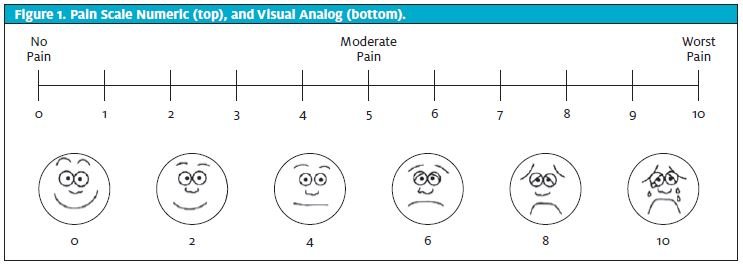

There are many ways to attempt to determine how much pain a patient is in. Once a diagnosis is made, the amount of pain an average patient with the same condition is usually in can be used to guide treatment. Clinical cues such as vital signs, restlessness, and behavior can all be used to quantify pain. “Pain scales” such as the 1-10 scale (Figure 1, top) where 1 is minimal pain and 10 is the most pain imaginable is the usual standard scale, but it is very subjective with many variables that make it difficult to standardize. Ethnicity, sex, and previous experience all contribute to a patient’s determination of the “number” for his/her pain. Fear of being undertreated may lead a patient to unconsciously or consciously inflate that number to obtain adequate relief. Visual analogue scales (Figure 1, bottom) are better, but seldom used, except in children.

Providers should also realize that these scales have different implications for patients in acute pain vs. chronic pain. A broken bone with a pain level of 9 for an hour may be better tolerated than low back pain with a level of 3 for 4 months. The broken bone may need a few doses of narcotic medication until healing begins, and the low back pain may need a more long-term solution.

Selection of Pain Medication

Selection of medication should be made based on level of pain, cause of pain, prior patient experience with medications, current medications, allergies, vital signs, and physician preferences. Goals must be set so that a patient has realistic expectations about the amount of relief he/she will obtain. For example, it is unreasonable for a patient with a large partial thickness burn to have get 100% relief from pain with one dose of medication. Clinical judgement should always be used to provide the most appropriate care to meet the unique needs of each patient.

Medications are just one facet of the pain-relieving cocktail we can provide to patients. Ice can be applied to injuries, heat to pulled muscles, exercises, and massage can all be used acutely to improve pain. Patients can be referred to pain management specialists for trigger point injections (or they can be done in urgent care if a provider is comfortable with them), steroid epidurals, or other interventional pain techniques. Chiropractic colleagues can also help with pain management for back and musculoskeletal concerns. Psychology, acupuncture, biofeedback and other complementary techniques can be added for chronic pain as desired.

Adjunctive medications can also be added. The use of muscle relaxants for back pain, neuromodulators for nerve pain such as herpes zoster, neuropathy, and radiculopathy, antidepressants, and steroids for acute exacerbations of chronic conditions all can decrease the amount of pain medications required to make a patient more comfortable. Urinary anesthetics such as phenazopyridine can be used for urinary discomfort. Topical anesthetic such as lidocaine for eyes, throat, skin, and mucous membranes are generally not recommended.

Specific Pain Medications

Acetominophen (APAP) inhibits central prostaglandin synthesis to exert its pain-relieving effect. It has no anti-inflammatory effect. Peak plasma levels are achieved in 30 minutes. Because the drug is metabolized in the liver, it should be used cautiously in patients with liver disease, alcoholism, and malnutrition. The maximum daily dose has recently been reduced to 4 g/day, which is the equivalent of 8 extra-strength tablets or 12 regular-strength tablets. Caution is recommended when using combination products, as overdose can occur easily.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) inhibit central and peripheral prostaglandin synthesis. Analgesic effect occurs in 30 to 60 minutes, with the anti-inflammatory effect occurring somewhat later. Responses vary by patient and drug; just because one formulation doesn’t work well does not mean another won’t work better. Sometimes trial and error is required to find the best fit for a patient. Examples include ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, ketorolac and more (Table 1). Enquire about the dose a patient took that did not work. Many times it is because they have been under dosing by taking only 1 or 2 ibuprofen 1 or 2 times per day (or more commonly, only one dose). Ketorolac has the added benefit of being available as a parenteral as well as a nasally administered formula. That can be helpful in patients who are vomiting or in severe pain. The role of COX-2 selective NSAIDs in acute pain management is unclear at this time, but they may be useful for chronic pain conditions, such as arthritis.

Tramadol was introduced in Europe in 1977 and later in the United States as an alternative to narcotics for pain management. It is a very weak muopioid receptor agonist that probably has the same mechanism of action as most opioids. It is about as efficacious as APAP/codeine in clinical trials. In most states it is not considered a controlled drug, but it may still cause withdrawal when stopped abruptly, a well as respiratory depression (especially in elderly patients), and physical dependence. Some states and the US military consider it a class IV narcotic and regulate it accordingly.

Opioid medications act on opioid receptors in the brain, including mu (µ), kappa (k), and delta (∆). They produce analgesia and also affect mood and behavior. Most cause respiratory depression and somnolence, euphoria or dysphoria. Most effects develop tolerance over time requiring increasing doses to achieve the desired response. Opioids can be given orally, intramuscularly (IM), subcutaneously (SQ), and some intravenously (IV). Common opioid medications are listed in Table 2.

| Table 1. Dosing Guidelines for Selected NSAIDs | ||||

| Generic (Brand) Names | Recommended starting dose (mg) | Dosing Schedule | Maximum Daily Dose (mg) | Comments |

| Aspirin | 650 | Q4 – 6h | 4000 – 6000 | GI side effects may not be well tolerated |

| Choline Magnesium trisalicylate (Trilisate) | 500 – 1000 | Q12h | 4000 | No effect on platelets, available as a liquid |

| Diclofenac (Cataflam, Voltaren) | 25 | Q8h | 150 | |

| Ibuprofen (Motrin and others) | 400 | Q6h | 3200 | Available as a liquid |

| Ketoprofen (Orudis, Oruvail) | 25 | Q6 – 8 | 300 | Available rectally and topically |

| Ketorolac (Toradol) | 10 | Q6h | 40 | Use limited to 5 days, first dose should be given IM or IV |

| Nabumetone (Relafen) | 1000 | Q24h | 2000 | Minimal effect on platelets |

| Naproxen (Naprosyn, Anaprox, Alleve) | 250 | Q12h | 1025 – 1375 | |

| Salsalte (Disalcid) | 500 -1000 | Q12h | 4000 | Minimal effect on bleeding time |

| Piroxicam (Feldene) | 10 | Q24h | 20 | |

| GI= gastrointestinal NSAID= nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. All NSAID doses should be decreased by ½ to 2/3 in the elderly and patients with renal insufficiency. Gastroprotective agents such as misoprostol, H2 blockers, sucralfate, and antacids can be sued to make these agents more tolerable. NSAIDs should be stopped 2-3 days before surgery. Adapted from McCaffery M, Pasero C: Pain: Clinical Manual, 1999. Mosby, 139-140. |

||||

| Table 2. Dosing and Conversion Chart for Opioid Analgesics | ||||

| Drug | Route | Equianalgesic Dose (mg) | Duration (hr) | Plasma Half-life (hr) |

| Morphine (standard) | IM | 10 | 4 | 2 – 3.5 |

| Morphine | PO | 30 | 4 | 4 |

| Codeine | PO | 300 | 4 | |

| Oxycodone | PO | 30 | 3 – 4 | 4 |

| Hydromorphone | IM | 1.5 | 4 | 2 – 3 |

| Hydromorphone | PO | 7.5 | 4 | |

| Meperidine | IM | 75 | 3 – 4 | 2 |

| Meperidine | PO | 300 | 3 – 4 | |

| Methadone | PO | 20 | 6 – 8 | 12 – 24 |

| Fentanyl | IV | 0.1 | 0.5 – 1 | 1 |

| Hydrocodone | PO | 30 | 3 – 4 | 4 |

| Tramadol | PO | 100 | 4 – 5 | 5.5 – 7 |

| Equianalgesic doses are compared to the standard, morphine 10 mg given IM. Adapted from www.acpinternist.org/archives/2008/01/extra/pain_charts.pdf |

||||

Pulling it All Together

General principles of pain management should be based upon “start low and go slow.” 1 If possible, start with APA and/or NSAID. Immobilizing orthopedic injuries goes a long way in providing pain relief. Apply ice or heat. If these simple measures are not enough, or a more severe illness or injury is present, add the lowest dose, lowest potency narcotic for only a few days. It is reasonable to start with combination hydrocodone/APAP or oxycodone/APAP. APAP/codeine has been shown in numerous studies to offer little benefit over plain APAP, adds the risk of addiction, and probably should no longer be used. It stands to reason that tramadol, which is as effective as codeine, has the same limitations, but can be used in select cases as an alternative.

Parenteral narcotics should be used with great trepidation in urgent care. The only reason they should be used is if a patient is in severe pain AND is vomiting uncontrollably. If possible, give an antiemetic, wait a bit, and then try oral methods. If that is not feasible, IM medications should be the next alternative. IV narcotic pain medication should hardly ever be given in the urgent care setting. Exceptions would include patients being transferred to a higher level of care for significant trauma, surgical emergencies, myocardial infarction or similar, or if there is no other option to treat severe pain available to you. IV narcotics allow a patient to experience an intensified euphoric effect that may contribute to abuse in the future.

Painful procedures such as reducing dislocations and large abscesses are also indications for parenteral medications. IM use requires less monitoring by the nursing staff and has less risk of complications. IV use has the benefit of rapid onset of action and possibly requiring a lower dose. Keep in mind that a patient will require a responsible party to drive him/her home and supervise after discharge.

Prescribe responsibly!! Some patients surely need narcotics for painful conditions and procedures. Think of how you would want your family members (or yourself) to be treated. Patients with kidney stones, herpes zoster, serious fractures and dislocations, severe burns, and herniated discs with nerve compression can benefit with a 2- to 3-day course of narcotics until follow-up or definitive care can be arranged. If you do decide to prescribe a narcotic, give only a few days’ supply, transition to an NSAID as soon as possible, and re-evaluate if a patient is not better in a few days. Transfer care to primary care physician or specialist for further care. Want patients of the addictive potential and dangers of misuse of narcotics. Oddly, a lot of patients don’t know and will actually be reluctant to take narcotics if you explain it to them.

Studies have shown that there is little risk of addiction in patients who have had no history of substance abuse. 5 Ask in your history if this has been a problem in the past. Conversely patients with untreated or undertreated pain may engage in drug-seeking behavior not because they are addicts, but because they are still in pain! This is called pseudo-addiction. Consider this: surgeons routinely prescribe narcotics at discharge from the hospital for their postoperative patients. Most people either don’t fill the prescription or leave the bottle in the medicine cabinet until it expires. These patients do not end up drug addicts. In our legal system it is better for 10 guilty men to go free than to have one innocent man falsely convicted. To parallel this in our profession, is it better for 1 or 2 drug seekers to get a few pills of narcotics they do not need for pain than to have one real patient in pain whose suffering goes unrelieved?

Be ever mindful that meeting a patient’s demands for pain medication may not be in the patient’s or the clinician’s best interest. You can actually get sued for “causing” a patient’s addiction. The state and Drug Enforcement Administration monitor your prescribing and may sanction you if you write too many narcotics. These include loss of prescribing privileges, fines, and even loss of license. More on this in Part II.

Conclusion

Illness and injury cause pain. Patients need relief of pain and come to us not only for a diagnosis and treatment but also for relief or pain and suffering. Management of pain should be based on the correct diagnosis, a thorough history, an understanding of both the pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical options available, and preferences of the physician. Patient education and open communication should always be the foundation for a therapeutic and successful patient encounter.

Part II of this series will discuss the entity of chronic pain, give a brief description of management techniques employed by pain specialists, and explain how to evaluate these patients who are likely to be abusing or diverting narcotics will also be discussed.

| Case Study: Acute Patient #1 |

| A 27-year-old woman “missed a step” and twisted her ankle. She complains of 5/10 pain, swelling of her lateral malleolus, and is unable to weight bear even one step due to severe pain. On exam, she has swelling and bruising of the lateral malleolus, point tenderness at the anterior talofibular ligament, and severe pain with inversion of the foot. X-ray shows an avulsion fracture distal to the lateral malleolus. You diagnose a second-degree sprain. The patient asks you how you are going to manage her pain.

Short leg splinting, crutches with no weight-bearing, rest, ice and elevation are the first methods of pain control in this situation. If pain medicine is required, a high-dose NSAID is all that should be provided. Go over prescription-strength doses of ibuprofen and naproxen with the patient, keeping in mind that NSAID treatment often fails because patients are not taking enough. |

| Case Study: Acute Patient #2 |

| A 33-year-old male presents with sudden onset of severe left flank pain radiating to the left groin 2 hours ago. He has nausea and vomiting. He is pacing around the room and unable to get comfortable. His vital signs are normal. He took 2 ibuprofen at home and then vomited. His urine is positive for blood. You diagnosis a kidney stone, give a liter of normal saline IV, and ask the nurse to strain the patient’s urine. The patient wants to know what the plan is for pain management, since he vomited the ibuprofen.

IV fluids alone are often great at alleviating the pain of renal colic. If the patient is vomiting, he should receive an antiemetic such as ondansetron or prochlorperazine. Ketorolac can be given IV. If his pain does not respond to these measures, narcotics may be warranted. If the patient is comfortable with just the ketorolac, he can be sent home on ibuprofen, naproxen, or oral ketorolac. A few pills of a narcotic in case his pain becomes worse may keep him out of the ED so he can get his computed tomography IV pyelogram as an outpatient. Hydrocodone or oxycodone/APAP combinations are useful in this circumstance. Be sure the patient has a prescription for an antiemetic as well so that he can keep his ibuprofen down. |

| Case Study: Acute Patient #3 |

| An 18-year-old female comes to urgent care after spilling boiling water down both anterior thighs 3 hours ago while cooking spaghetti. At home she rinsed the area with cool water, took one ibuprofen, two APAP, and put aloe cream on the burn. She is crying. Her heart rate is 140 bpm, and the remainder of her vital signs are normal. She looks uncomfortable. Upon examining her burns, she has large blisters, mostly intact on 2/3 of both anterior thighs (about 12% total body surface area). She is going to follow up with the local burn in 2 days. She asks for “something strong” for pain.

Burns hurt, and although ibuprofen is great for the pain and inflammation of burns, it is not enough pain control for this patient. Because she is following up with the burn clinic, you only need to give her 2 days of narcotics. Again, hydrocodone or oxycodone/APAP combinations are the best choice. Keep in mind 2 days of pain medicine is not 4 pills. Two tablets every 4 hours for 2 days with a maximum daily dose of 8 pills is 16 pills. If you have narcotic medicines in your clinic you may want to give her some before removing the dressings and cleaning the patient’s wounds as those procedures can be painful. |

References

- Resnick L. What a Pain!. JUCM. 2012; 6(10): 1

- The Joint Commission Facts about pain management. January 1, 2001. http://www,joint-commission.org/assets/1/18/pain_management.pdf

- Okie S. “A Flood of opioids, a Rising Tide of Deaths” N Engl J Med. 1981; 1363; 21: 1981.

- CDC MMWR. Vital Signs: Overdoses of Prescription Opioid Pain Relivers- US, 1999-2008. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm?scid=mm6043a4w

- Bertakis KD, Azari R, Callahan EJ. Patient Pain in Primary Care: Factors that Influence Physician Diagnosis. Ann Fam Med. 2004; 2(3): 224.

- http://www.healthyohioprogram.org/ed/guidelines