Urgent message: There is no diagnosis so “common” that it cannot be missed or mistaken for something else. A systematic approach to the history and examination are crucial to reaching the right conclusion and positive outcomes.

Lee A. Resnick, MD

Every now and then, medical school pearls are wrong. You remember: “When hearing hoof beats in Central Park, don’t go looking for zebras.” It may be true that zebras are infrequent visitors to New York City parks, but there are zebras in the Central Park Zoo, so theoretically you could see one.

By and large, the commonalities in medicine prevail, but no one wants to miss the zebra.

A systematic approach is critical to the care of the urgent care patient. Applying this approach, even for the most common presentations, can help identify the needle in the haystack, and prevent unnecessary harm to our patients.

The following case report exemplifies the importance of this concept.

Case Presentation

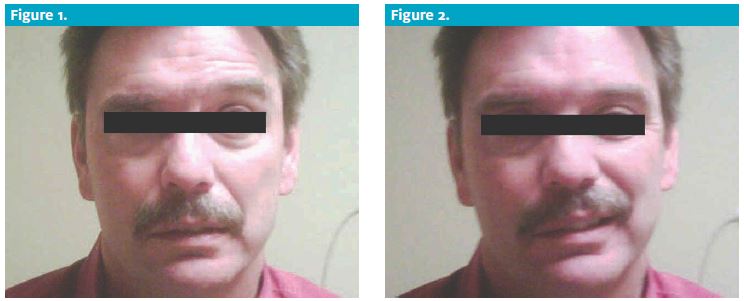

ML is a 51-year-old male with no past medical history who presents to the urgent care center with 36 hours of intense, sharp, right-sided ear and temporal pain; onset was followed by 24 hours of dramatic right facial droop.

Pain and droop persisted throughout the day. ML cannot close the right eye. He denies weakness or numbness of the extremities, slurred speech, dysarthria, confusion, or memory loss. He also denies rash, fever, vision impairment, or photophobia, as well as trauma, neck pain, and stiffness.

Past medical history is negative for migraine, CVA, MI, and aneurysm. He has no history of diabetes or hypertension.

On exam, he has a grossly apparent right-sided facial droop. Other findings:

- BP: 130/90

- HR: 83

- Temp: 97°F

ML was alert and cooperative. He had a loss of brow furrowing on the right, and complete paralysis of the fa- cial nerve. There were no skin lesions present. The tym- panic membranes were clear, as were the canals. There was no mastoid tenderness. He had mild tenderness of the temporal artery on the right.

Examination of the right eye revealed inability to close that eye. PERRL, EOMI, and the fundoscopic exam were normal. There were no corneal infiltrates or ulcers. The tongue extended midline. Examination of the oropharynx reveals a distinct cluster of erythematous

vesicles on the right side of the soft palate.

These lesions do not extend past midline. No other mouth ulcers were seen. There was no neck stiffness or carotid bruits.

CV exam was unremarkable.

The neuron exam was otherwise unremarkable, ex- cept for slightly decreased grip strength on the right.

A head CT was obtained secondary to the unexpected finding of decreased right grip strength. This was negative.

CBC w diff was unremarkable, and sed rate was 5.

Diagnosis

This is a classic presentation of Ramsay-Hunt syndrome, a constellation of facial nerve palsy in association with herpes zoster reactivation (shingles) along the facial nerve. In this case, the patient had the most unusual pres

entation of unilateral palatal vesicular lesions; lesions are most frequently discovered pre-auricular, on the TM it- self or, less frequently, on the soft palate.

Such patients are often misdiagnosed with Bell’s palsy, due to the inconspicuous locations for the characteristic lesions, and the oft-delayed onset of rash. Missed or de- layed diagnosis leads to unnecessary morbidity.

Hearing loss, chronic pain, and persistent facial droop are common complications.

Keys to the differential

- Bell’s palsy: Diagnosis of exclusion. Other causes must be ruled out first. Both the upper face and lower face are affected. Pain is usually mild to moderate

- Cortical stroke/other central lesions: Due to duplicative central innervation, the upper part of the face (brow) is spared. This remains the hallmark distinction between central and peripheral causes of facial droop.

- Ramsay-Hunt syndrome: Facial paralysis with characteristic zoster lesions. Look carefully in the ears and mouth, as lesions may be difficult to appreciate in these locations. Pain is often severe compared with Bell’s palsy.

Management

Patients should be started immediately on systemic steroids: prednisone 40 mg/day to 80 mg/day for seven days, with or without a taper. Antivirals (valacyclovir/ famciclovir) are usually prescribed, though their bene- fit in addition to corticosteroids is uncertain.

This case of Ramsay-Hunt syndrome is an important reminder that even routine presentations mandate a complete and systematic approach. You never know when one of those zebras will break out of the zoo and stomp through Central Park.

Resources

- Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1323-1331.

- Lockhart P, Daly F, Pitkethly M, et al. Antiviral treatment for Bell’ palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4) :CD001869.

- Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(5):340-346.

- Aizawa H, Ohtani F, Furuta Y, et al. Variable patterns of varicella-zoster virus reactivation in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Med Virol. Oct 2004;74(2):355-360.

- Uscategui T, Doree C, Chamberlain IJ, et al. Antiviral therapy for Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster op- tics with facial palsy) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Oct 8 2008;CD006851.