Published on

Urgent message: Determining compensation for urgent care physicians is a challenge, particularly given the current health care environment. This article provides guidelines for achieving fair compensation based on reliable metrics and objectivity.

RICHARD M. CAMERON, MHSA, CMPE and RICK E. WEYMIER, MBA, FACMPE

Introduction

Physician compensation presents one of the greatest challenges to the success of an urgent care practice because it has an impact on practice culture, physician interelationships, and the ability to attract and retain quality physicians. The current health care environment is not conducive to promoting steady growth, or even maintaining what physicians may perceive as fair compensation for their work effort. Physician compensation is a sensitive issue that must be approached with caution, reliable metrics, and objectivity.

Urgent Care and Physician Compensation

Urgent care services can be provided in a variety of set- tings, which have significant consequences to the level and quality of care provided today and in the future. These settings include extended hours in both primary care and specialty care offices, and stand-alone outpatient urgent care centers, hospital emergency rooms, and free-standing emergency care centers. Physicians who typically provide these services are in urgent care, family practice, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Furthermore, orthopedists , sports medicine physicians and therapists continue to move into this space through the advent of walk-in sports injury clinics. Overall trends for urgent care physician compensation indicate an increase in compensation with a 5% change for urgent care physicians and a range of 3% to 6% for the primary care physicians who provided urgent care services between 2011 and 2012, according to Medical Group Management Association

– American College of Medical Practice Executives compensation survey results.1

With the advent of Accountable Care and the ensuing push to create a Patient-Centered Medical Home system of delivering and coordinating care, along with the projected shortage of primary care physicians (from which the body of urgent care physicians are recruited) and the continuing increase in the number of urgent care centers across the country, we anticipate that there will be significant competition to recruit and retain urgent care physicians. This competition will put increased pressure on physician compensation levels in an era of declining reimbursement. Independent urgent care centers will also need to compete with hospital systems as they continue to incorporate urgent care services into their integrated delivery systems.

It is likely that there will continue to be a space for independent urgent care centers, albeit with a higher level of competition from other specialties and health systems. Urgent care physicians will be held to the same standards of quality, outcomes, and patient satisfaction that will be driven by quality metrics and value based reimbursement. An effective strategy for growth and success should include pursuit of formal relationships with health systems, independent physician practices, and insurance carriers. Urgent care services need to be considered as part of the continuum of health care services and viewed as complementary and working in partnership within the health care delivery system, particularly as health care reform is implemented.

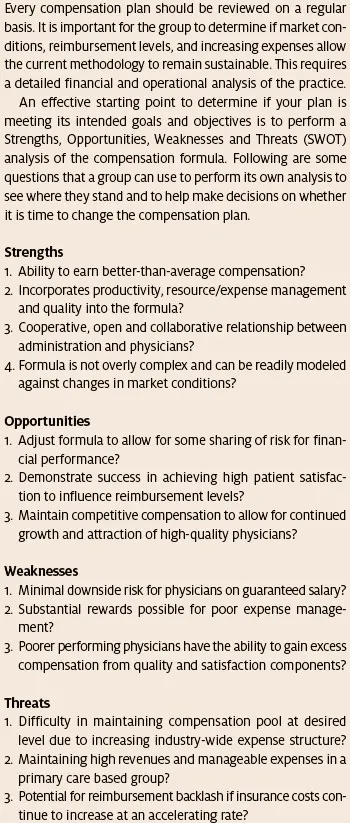

Key Tenets in Physician Compensation

The primary goal of every physician compensation formula is to make it representative of the work effort and overall contribution put forth by the physician. This should be balanced by what is fair and equitable, acheivable within the reimbursement and cost structures, and mutually agreed upon by the physicians. A significant ongoing challenge is that reimbursement continues to decline while the overhead cost structure continues to increase, and physicians want to maintain a better-than-average level of compensation. The environment is constantly changing, thus once a compensation formula is put in place, the organization cannot expect that formula to remain static nor can the physicians expect that an unmovable baseline has been established. The organization must take the time to carefully assess and evaluate the physician compensation formula on a regular basis because physician productivity, payor mix, physician behavior, and the cost structure all have an impact on compensation. Physician compensation evaluation should be a standard recurring event, reviewed on a regular basis as a part of the annual financial and operating assessment process.

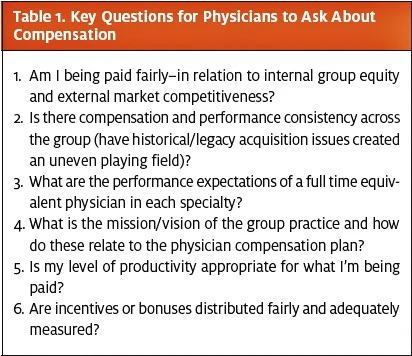

Health care is not totally immune to the cost consideration pressures that other industries have faced, which have caused dramatic shifts in consumer buying pat- terns and the ways that suppliers of goods and services approach their customers. Although health care remains partially isolated from some of the pressures (as premium rates continue to go up, new technology investments are made and health care organizations retain some price point leverage), this is rapidly changing. It appears as if employers are finally stating that “enough is enough” and it is not a matter of if, but when Medicare reimbursement cuts will take place. If history is true to form, the commercial payors will follow suit shortly thereafter. In fact, some commercial payors are already accelerating the inclusion of higher forms of “value-based” services and outcomes to just maintain current reimbursement levels. The fact of the matter is that the pool of funds available to support physician compensation expectations will be severly constrained and changed in the near future with the expected implementation of additional pay-for-outcomes-based care. Sustaining a fair compensation plan is not as simple as it appears. The basic formula is that: (1) you provide services; (2) you bill for those services; (3) your business office collects for those services; (4) you pay your over- head; and (5) whatever is left over is available to pay the physician. In reality, physician compensation often causes a great deal of discussion and contentiousness in an attempt to arrive at what will likely be a very short- term solution. Key components of the formula include the age of the physician, the scope of practice, hours desired to work, on-call coverage, full vs. part time work, overhead allocation formulas, vacation time, medical/pregnancy leave, income guarantees, outside directorships and industry benchmarks. Understanding the Burning Platform–from the physician’s perspective–includes addressing the questions listed in Table 1.

Payor mix is the largest contributing factor to most private practice physician compensation formulas. Your payor mix will largely determine your ability to create the pool of funds that is available to pay practice expenses and meet physician compensation expectations. In some cases, an affiliation or employment by a health system may result in additional funds subject to the appropriate legal constraints and configurations. Most private practices focus on negotiating with the large insurance carriers. However, an increasing amount of financial responsibility is shifting to the patient and reimbursement levels from government payors will decrease in the future. The organization needs to have the necessary systems in place to demonstrate quality, outcomes, and patient satisfaction in the future in order to take advantage of value-based reimbursement and avoid payment penalty reductions from government payors.

A major devisive force within a practice when coming up with a compensation formula typically ties into each individual physician’s payor mix. It is very unusual in a practice for every physician to have the same payor mix profile. Unless the group can collectively agree that all physicians will get paid the same amount for work effort, quality, outcomes and patient satisfaction, payor mix issues will often drive physician behavior in a manner that is destructive to the long-term success of a practice. For example, many physicians will gravitate towards those payors that are the most profitable and will also implement access roadblocks to those payors that offer lower levels of reimbursement or represent a higher hassle factor.

Overhead and other expense allocations are becoming increasingly important variables in determining the physician compensation formula, especially in integrated delivery systems that use a revenue-minus-expenses formula, even when the physician is on a guaranteed salary. Other areas of contention involve determining which expenses should be direct expenses and which should be indirect and shared by all physicians. One common flaw in many physician compensation formulas is that a highly productive physician actually consumes a higher level of indirect expenses (check in, billing, medical records), yet the cost to that physician is significantly less as a percentage of their compensation than physicians who are producing at an acceptable level, albeit at a lower rate.

Essential Attributes of Compensation Models

There are many variations of physician practice models that impact physician compensation. The two major forms of practice are private practice and hospital or health system-employed practice and the other variations include employment in a group practice (such as Kaiser Health Plan). An emerging trend is the movement by major insurance carriers to employ physicians to round out their networks.

Private Practice. Private practice medical groups operate much like any independent business where the owners of the business assume responsibility for the management of the business and all the risks associated with running the business. The owners of the private practice retain the freedom to direct the practice as they see fit (within the constraints of health care laws and regulations). There is a significant focus on generating high patient volume, managing overhead costs and taking a major part in governance and management. Many private practices are moving to a higher mix of employed physicians, but the main focus remains on creating a partnership and ownership track. There is a strong belief that if you own part of it, you will work harder to make the organization a success. In addition, private practice often offers the owners access to additional revenue sources such as ancillary services and real estate investments.

Hospital or Health System Employed. The number of physicians employed by hospitals has grown by 32% since 2000, raising the number of physicians employed by hospitals to about 212,000.2 This means that approximately 25% of all physicians are now employed by hospitals. Another study indicated that more than half of practicing physicians were employed by hospitals or integrated delivery systems.3

In light of the current market drivers and ongoing implementation of health care reform legislation, it appears that the trend toward a greater percentage of employed physicians will only further accelerate. Under the employed model there is typically some sort of base salary with incentives for productivity, quality, out- comes, patient satisfaction, and participation in committee work or other administrative work. There is a high expectation of standardization and the cost structure is usually managed by a practice management arm of the system. Access to ancillary service revenue is generally very limited or excluded, and there are Stark law limits on how such services can be considered within the physician compensation plans. In most cases, investments in outside entities by employed physicians is highly restricted and often prohibited. This practice model continues to evolve and many industry experts feel that this structure offers the best opportunity to meet the changes occuring in the health care industry. In addition, most of the newest physicians in the marketplace are open to the employment model because it provides a sense of security and a balance between professional and personal life with minimal risks associated with running a business.

Irrespective of the model, the overriding challenge in designing a physician compensation system is to balance the various countervailing forces that have the potential to put significant stress on the organization. The desire to provide physicians with a degree of compensation stability and reward high productivity, quality and outcomes, must be balanced with the need for organizational viability and compliance with federal regulations including fair market value considerations, clinical documentation and appropriate coding.

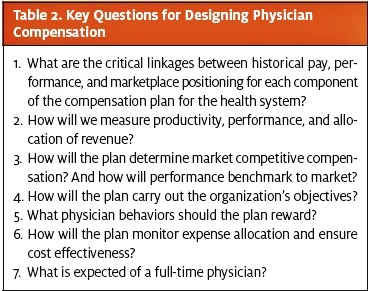

So what should you do? Start by asking the questions listed in Table 2.

Summary

This article offered a broad overview of the trends and factors that go into determining physician compensation. The following are the recommended core principles that any physician compensation plan or formula should seek to balance:

- Every compensation formula should allow a physician to enjoy personal and professional satisfaction and promote the financial viability of the

- Although physicians want to earn an excellent wage, financial considerations should never get in the way of clinical quality and patient satisfaction with services

- The compensation formula needs to be sensitive to and anticipate changes in the health care

- The compensation formula needs to be flexible and enforceable, and easy to understand, calculate, and

- The compensation formula needs to be structured in such a way that a physician has a chance to earn a reasonable

- Even if the compensation formula includes a base salary or a floor, there needs to be some productivity component of the

- As the health care industry moves toward value- based reimbursement, the formula should reward those who achieve the required

- Direct and indirect costs need to be allocated fairly and individuals should not be insulated from certain costs and overall expense management to the detriment of others in the

- The overall success of the plan design is to ensure that it promotes a level of compensation and aligned incentives that are internally equitable and externally competitive. Without this, a practice will not be able to recruit and retain desired physicians or sustain

References

- 2011 and 2012 Medical Group Management Association, Physician Compensation and Production Surveys

- 2012 Edition, American Hospital Association Hospital Statistics

- Kocher R, Sahni Hospitals’ race to employ physicians–the logic behind a money- losing proposition. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1790-1793.