Urgent message: Most urgent care operators are well aware of the need for strong, clear policies on sexual harassment among team members. Your responsibility to protect your employees doesn’t end there, though. Situations in which the harasser is a patient present unique challenges—and consequences.

Suzanne C. Jones and Roma B. Patel

INTRODUCTION

The #MeToo movement may have begun with high-profile actresses in Hollywood publicly acknowledging years of inappropriate behavior at the hands of powerful men like movie mogul Harvey Weinstein,1 but it quickly evolved into something much broader. #MeToo has touched almost every industry across the country, from hospitality and technology to manufacturing and agriculture.

Unfortunately, urgent care, along with the healthcare industry in general, is no exception. Sexual harassment of healthcare providers has been a pervasive problem for decades. As a result, most urgent care employers are familiar with Title VII2 and other laws that prohibit sexual harassment in the workplace. Most know to establish, post, and enforce policies prohibiting sexual harassment by coworkers and supervisors, to investigate harassment claims made by employees, and to impose disciplinary action on staff members if they violate the harassment policy.

The consequences of a business operator failing to do the right thing in regard to sexual harassment have never been greater—and that’s in addition to the human cost. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) launched 50% more sexual harassment lawsuits in the year following the start of #MeToo than in the previous year; further, the EEOC has seen a spike in the number of sexual harassment claims received.3 Gone is the era where companies can fail to take action after learning about sexual harassment or abuse occurring in the workplace without exposing themselves to serious, multiple risks to the business.

What urgent care center employers may not be aware of is that liability for sexual harassment of employees is not limited to acts by coworkers and supervisors, but also extends to third parties in the urgent care setting—including patients. Sexual harassment by patients may be particularly likely to occur in urgent care and hospital ED settings, where individuals may feel emboldened by the relative anonymity of seeing providers who don’t know them. Risk is likely to be especially great when dealing with patients who are inebriated, on drugs (or seeking drugs), very ill, elderly, or disoriented.

Here, we examine why urgent care center operators should have zero tolerance for patients who sexually harass or abuse staff members. Failure to adequately protect employees from abusive patients can negatively impact the work environment and employee health, and negatively affect the quality of patient care while increasing risk for medical errors.4

Tolerating abuse of staff by patients also can have a negative financial impact. Sexual harassment in the workplace generally results in lower staff morale, higher turnover, and diminished productivity. In addition, failure to protect healthcare employees from sexual harassment and abuse from patients (or other third parties present in the urgent care center) exposes urgent care centers to liability for sexual harassment of their employees.

We will also discuss practical steps that urgent care operators can take to protect their employees, the quality of care, and themselves from lawsuits based on sexual harassment of staff by patients and other third parties.

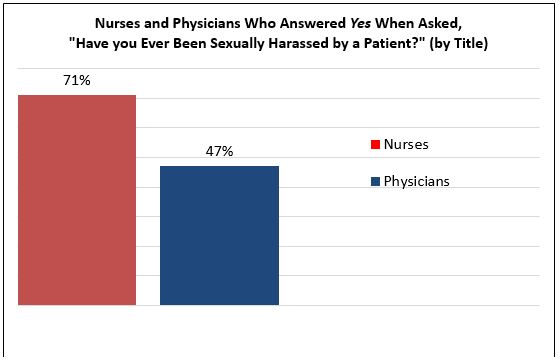

Data source: Frellick M. Harassment from patients prevalent, poll shows. Medscape. February 1, 2018. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/892006. Accessed July 16, 2019.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND PROHIBITED RETALIATION DEFINED

Title VII prohibits both sexual harassment and retaliation.5 Under Title VII, “sexual harassment” encompasses any unwelcome conduct that is based on sex and is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment, or conduct that makes some aspect of one’s employment conditional on submission to sexual advances or favors, inappropriate verbal communications, physical interactions, or pictures.6 Employees subjected to “materially adverse” actions by their employer because they have lodged complaints of sexual harassment can assert a separate Title VII claim for retaliation.

On its website, the EEOC defines sexual harassment in language similar to Title VII:

Harassment can include “sexual harassment” or unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature. Harassment does not have to be of a sexual nature, however, and can include offensive remarks about a person’s sex. For example, it is illegal to harass a woman by making offensive comments about women in general. Both victim and the harasser can be either a woman or a man, and the victim and harasser can be the same sex. Although the law doesn’t prohibit simple teasing, offhand comments, or isolated incidents that are not very serious, harassment is illegal when it is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment or when it results in an adverse employment decision (such as the victim being fired or demoted). The harasser can be the victim’s supervisor, a supervisor in another area, a coworker, or someone who is not an employee of the employer, such as a client or customer.7

Common examples of sexually harassing conduct by patients include making suggestive or lewd comments, as well as taking advantage of physical proximity by groping or other types of inappropriate or lewd behavior, sometimes involving patient nudity, disrobing, or touching private areas. Harassing behavior also can come from a patient’s companion or family member. For example, a patient’s family member might repeatedly ask a nurse for a date, or make frequent comments that are uncomfortable or unwelcome about a provider’s appearance. Such behavior undermines the professional competence of providers by making their gender and sexuality the focus of the interaction.

According to the United States Supreme Court, “retaliation” under Title VII means the employer’s action following a complaint of sexual harassment is severe enough to “dissuade a reasonable worker from making or supporting” a sexual harassment claim, but “need not affect the terms and conditions of employment.”8 Retaliation in healthcare settings can take a range of forms. For example, after reporting patient harassment an urgent care worker might be assigned to mostly unpleasant shifts or shifts that interfere with family responsibilities. Or, reporting abusive patient behavior may result in reduced hours, an increase of unpleasant tasks, undesirable pairing assignments, diminished opportunities to participate in special assignments that may lead to advancement, or other types of retaliation against “squeaky wheels”—which can have both a psychological and economic impact on workers who rely on meeting certain time or output requirements.

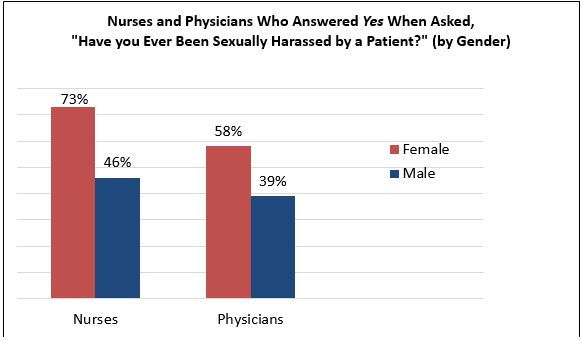

Data source: Frellick M. Harassment from patients prevalent, poll shows. Medscape. February 1, 2018. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/892006. Accessed July 16, 2019.

WHY IS SEXUAL HARASSMENT PERVASIVE IN HEALTHCARE?

There are many possible explanations and underlying causes for the pervasiveness of sexual harassment in healthcare. Factors that make healthcare unique and have contributed to the problem include the physical proximity that workers have to each other and their patients—many times in areas where there are few or no witnesses—as well as the intellectual and emotional intensity of caretaking and having such a large number of healthcare workers in nontraditional supervisory models.6

A ‘Patient-First’ Sensibility

Despite the growing number of women in provider roles and a greater understanding that this behavior is damaging, the historical reasons behind sexual harassment in healthcare remain. One is the unique dynamic between the patient and the treatment team—where quality of care and healing is the paramount goal, and physicians, nurses, and others are driven by ethical obligations to provide care for the patient notwithstanding patient abuses. The professional philosophy which guides many healthcare workers places a high value on tolerating unpleasant or distressful circumstances or “toughing it out” for the sake of patient care, even to the detriment of one’s own self. The medical profession is especially rigorous, and signs of weakness or vulnerability in healthcare providers typically are not met with helpful hands.

Reliance on Patients as Customers

The competitive nature of healthcare as a business may also lead employers to look the other way when patients harass providers. To the extent a patient has a choice with respect to which specific urgent care center, hospital, or other healthcare providers, competing entities want to be the entity selected. Organizations may be inclined to have workers tolerate patient misbehavior as a function of client relations, along the lines of the adage “the customer is always right.”

Outdated Stereotypes

Society’s fetishization of the nursing profession also has contributed to a lack of respect for the bodily autonomy and dignity of nurses. Despite being highly trained, experienced, and capable, female nurses are still treated like accessories to the doctor, rather than providers in their own right, by some patients. This is especially common with elderly male patients, who may have significant difficulty taking instructions from a woman.

The longstanding prevalence of patient sexual harassment in urgent care and ED settings in particular probably results from a combination of many factors already discussed, including the type of patient mix involved (ie, patients inebriated, on drugs/or drug-seeking, elderly or disoriented), the typically “hands-on” nature of interaction when treating patients in such settings, and other common circumstances, such as the fact that care often is provided to patients who are only partially clothed or might be naked, behind a curtain or in a private room—which can allow some to feel emboldened to behave in ways they otherwise might not if fully clothed and not behind a curtain, alone with a provider.

IMPACT OF TOLERATING PATIENT HARASSMENT AND ABUSE

Failing to properly address sexual harassment by patients can have multiple personal and organizational consequences on an urgent care center. Each incident of abuse that goes unaddressed contributes to the overall stress of the workplace and reinforces societal legitimacy of this destructive pattern of behavior.

People who are sexually harassed often have to “numb” themselves in order to carry on; over time, however, doing so eventually takes a toll. Sexual harassment is not only personally degrading, but extremely stressful and exhausting—adding a heavy burden to the already high demands of working in a busy urgent care center.

In addition to complex emotional and psychological wounds, sexual harassment by patients can trigger unique internal conflict for healthcare providers, since many view their profession and their care for a patient as a calling. When the very core of that calling is the source of deep distress, a provider’s inclination to suppress the feelings that result from such behavior is even stronger. The longer the historical tendency to ignore the problem continues, the more the psychological and physical impacts on workers in healthcare are likely to grow, reinforcing the societal legitimacy of this destructive behavior and negatively impacting both the healthcare workers and the care being provided.

POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES TO A PROVIDER’S CAREER DUE TO PATIENT SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Providers who suffer harassment at the hands of a patient may fear coming forward for a number of reasons. Most prevalent among them may be the perception that making a complaint could derail their career.

Society tends to think of medical providers as being almost superhuman. Patients trust them with life-affecting decisions and with the most intimate parts of themselves. Patients trust their doctors to know best, and to be “better” than they are. As such, providers must perform under pressure while maintaining a calm façade.

The terminology used in reporting harassment can be an obstacle in itself. No one wants to be labeled a victim, especially in a profession in which being perceived as weak can carry a professional toll. For doctors, especially, appearing to be mentally strong and in control is important for building the trust and respect of coworkers and patients alike. Physicians who are sexually harassed by patients report a loss of confidence, including in their professional abilities.9

Unaddressed sexual harassment may also affect a provider’s ability to communicate confidently with patients and colleagues, ultimately diminishing their ability to meet—and the facility’s prospects for meeting—the standard of care.

It also is likely to increase the possibility of medical errors. Studies have shown that this is due, in part, to disruptions in communication and breakdowns in teamwork, as workers “on guard” for sexual harassment may lose focus on important clinical tasks. It is not difficult to imagine a direct link between sexual harassment and other disruptive behaviors in an urgent care setting, as well as adverse patient outcomes and medication errors. These negative impacts also may ultimately lead to broader legal exposure.

Urgent care employers who turn a blind eye to patient sexual harassment of their workers are not only violating Title VII and inviting sexual harassment lawsuits; they also are likely to experience a drop in the quality of care and possible increase in malpractice claims.

CONSEQUENCES TO THE BUSINESS FOR FAILING TO ADDRESS PATIENT SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Urgent care centers and other healthcare organizations that fail to adequately respond to patient sexual harassment of their workers are likely to experience negative financial impacts, including a loss of quality workers, a toxic workplace culture, lower productivity, and the potential of negative public relations exposure.

Specifically, employers should be mindful that ignoring sexual harassment (or any severe, potentially illegal problem) may lead to negative public scrutiny and damage to their brand. This is especially true given the prominence of social media today. Internet platforms offer employees an opportunity to connect and share their experience like never before. Accordingly, healthcare organizations that are unwilling or unable to adequately address harassment not only will have difficulty retaining talented workers, but may also have trouble recruiting quality workers—particularly in this era of provider shortages.

Effects of the Social Media Age

When workers are unhappy, it can be difficult for them to put on a “happy face” and devote the proper enthusiasm to their jobs. Patients pick up on this, and have many highly visible online platforms available to voice complaints about their experiences with urgent care centers. Patients who receive treatment in a negative workplace—for example, a workplace experiencing constant employee turnover, and populated with distracted workers and unhappy staff—may share their negative perceptions, experiences, and critical views online. Healthcare employers should not underestimate the role that social media and public reputation can play when sexual harassment goes unaddressed. The #MeToo movement’s virality is the direct result of social media’s ability to magnify voices. An organization that gains an online reputation for failing to protect workers is very likely to find it challenging to attract talented providers, and also will not present as an appealing choice when patients are choosing where to get treatment.

Ironically, operators who choose to tolerate patient misbehavior and sexual harassment of their staff as a misdirected “customer relations effort” (á la “the “customer is always right”) in order to draw in business and be more competitive may find that the toxic atmosphere created by such an approach is much more damaging to their brand and reputation than taking the opposite approach of implementing and enforcing a zero-tolerance policy regarding patient harassment.

Potential for Civil Liability Over Sexual Harassment of Employees by Patients

As noted, the EEOC’s regulations on sexual harassment specifically state that “employer[s] may also be responsible for the acts of non-employees, with respect to sexual harassment of employees in the workplace.”10 Consistent with the EEOC regulations, most courts that have addressed the issue of an employer’s liability for nonemployee sexual harassment in the workplace have determined that employers are liable for the harassment of an employee by a nonemployee when 1) the employer knows or should have known of the conduct and 2) fails to take immediate and appropriate corrective action.11

Multiple cases filed by the EEOC and healthcare workers illustrate the very real liability exposure that exists for employers who fail to take employees’ complaints of patient harassment seriously. Title VII requires urgent care centers (and all healthcare employers) to treat such complaints seriously, and to take reasonable steps to protect an employee once harassing patient behavior is known.

Purely verbal offensive conduct can be sufficient

Healthcare employers may mistakenly assume that employer liability for third-party sexual harassment conduct will only arise in situations that involve uniquely extreme and physically abusive patient conduct. They would be wrong. The EEOC and courts regularly find that employers were required to take seriously, and immediately and adequately address, employee complaints that involve purely verbal offensive conduct.

For example, the EEOC filed a Title VII sexual harassment lawsuit against Southwest Virginia Community Health System (SCVHS) for subjecting a female employee to a sexually hostile work environment after the female was repeatedly subjected to sexual harassment by a male patient.12 The harassment involved unwelcome sexual comments by the patient in person at the clinic, and by telephone when he called the clinic. His comments included that he was “visualizing her naked” and suggestions that she have sex with him.

Although the receptionist complained to her supervisor, the supervisor did nothing to stop the harassment. SCVHS’s settlement with the EEOC in 2013 required it to pay $30,000 to the receptionist, and also to “conduct training for all employees on sexual harassment prevention; post a notice about the settlement; provide a copy of its sexual harassment policy to all employees; and report sexual harassment complaints to the EEOC.”12 The EEOC’s press release announcing the settlement warned: “Employers have a responsibility to prevent sexual harassment not only by coworkers, but also by third parties, including patients and customers. Employers need to adopt measures to end sexual harassment that has been reported to the appropriate supervisor regardless of who is perpetrating the misconduct.”

Employers can be deemed to have ‘sufficient knowledge’ without a report or direct knowledge

Other cases illustrate that healthcare employers can be found liable for sexual harassment even if the employee cannot show that the employer actually saw patient harassment occur, and cannot show that the employer was directly notified about a specific incident of patient harassment. This is because an employer’s constructive notice of patient harassment can be sufficient under the law. “Constructive” notice will be found if harassing behavior by a patient (or patients) is “so pervasive and open that a reasonable employer would have had to be aware of it.”13

A recent example of a case involving constructive notice is Poe-Smith v Epic Health Servs.11 There, a female home health worker sued her employer for Title VII sexual harassment, this time perpetuated by a third party in the home where the patient was staying. For several months, the male homeowner directed sexual innuendos and inappropriate comments toward her. Ultimately, he bought her a maid’s costume and “told her she would have to model it,” then followed her when she left the room, pushed her and “smacked her on her buttocks.”11 The worker reported the final incident to her employer, but had not previously complained about the homeowner. The employer’s response was to immediately relieve her of the assignment and arrange a meeting between the worker and her managers to discuss the issue. The worker also was informed that the employer would meet with the homeowner. Based on these facts, the employer argued to the court (after the lawsuit was filed) that because it had taken immediate action, and its action had stopped the harassment, the worker could not prevail on her Title VII claim. The court disagreed and allowed the sexual harassment claim to proceed. The court reasoned that the employer still may be liable if the worker can prove that the employer was on earlier, constructive notice of the harassment.11 If so, its corrective actions to remove the worker from the home when it did, while appropriate, were not immediate and were thus insufficient.

Similarly, if an urgent care center has constructive notice that patient harassment is probably occurring based on past or other reported instances of harassment or abuse, the urgent care center may be deemed to have knowledge of the conduct and thus must take immediate and appropriate corrective action. If it fails to do so, it should be prepared to face a lawsuit from workers or the EEOC.

PROTECTING YOURSELF FROM LAWSUITS OVER PATIENT HARASSMENT OF STAFF

Consistent with the legal responsibility imposed upon urgent care employers by Title VII, and as made clear by the EEOC and the courts, urgent care employers must adopt measures targeted to end sexual harassment in the urgent care setting regardless of who is perpetrating the misconduct.

Under the law, urgent care employers must take immediate and appropriate action in response to all sexual harassment that the urgent care employer directly witnesses, all sexual harassment reported to the urgent care employer, and also all sexual harassment the urgent care employer does not directly witness or receive a complaint about—but that it nonetheless should know about because the harassment is “so pervasive and open that a reasonable [urgent care] employer would have had to be aware of it.”14

In summary, federal law requires healthcare employers to have a policy prohibiting sexual discrimination, and to consistently enforce it by taking sexual discrimination complaints seriously, and taking prompt and appropriate remedial action.15

Notably, Title VII does not obligate employers to succeed in eliminating all sexual harassment from occurring in the workplace. Title VII instead requires urgent care employers just to be vigilant in seeking to protect their employees by responding immediately to complaints, and taking reasonable measures to abate all sexual harassment that they know (or should know) is occurring in the facility, regardless of who is doing the harassing.

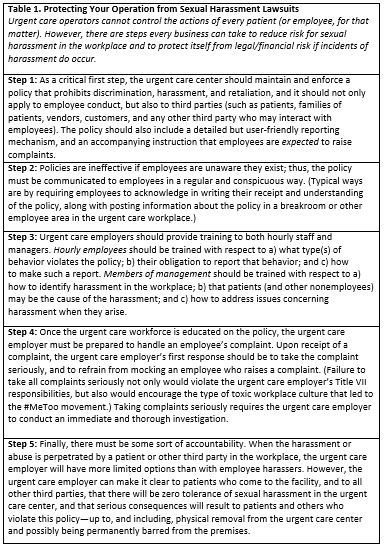

There are several steps you can take to protect your operation from such sexual harassment lawsuits. The most basic are set forth in Table 1.

REAL-TIME STRATEGIES TO ADDRESS PATIENT HARASSMENT

The urgent care center’s policy on sexual harassment should be uniformly enforced and optimally should incorporate measures that can be used to address situations of provider complaints about patient sexual harassment in real time, as they are occurring.16 The following “real time” measures can assist in immediately mitigating any additional harm a provider may be facing when treating an abusive patient.

- First, the policy could provide that supervising providers must make a sincere effort whenever possible to reassign providers to different patients when a provider has complained of patient sexual harassment.

- Second, the policy could provide that supervising providers are authorized to ask a security guard, if available, to stand outside the patient’s room when a provider who has been harassed is inside the room, so that the patient is aware of a protective presence nearby.

- Third, the policy could provide that if the harassment or abuse is especially distressing to a worker, the supervising provider should make a sincere effort to allow the provider being harassed to take a break, in order to get relief. Similarly, the policy could provide that when a provider has complained about sexual harassment from a patient but is still providing care to the patient, supervising providers should make arrangements so that that patient will only receive care from the harassed provider when accompanied by a companion provider. The harassed provider should not be required to be in a room alone with the harassing patient.

Use of Medical Records to Document Patient Behavior and VIP Patients

Providers should use objective language to thoroughly document sexually harassing and disruptive patient behavior in the medical record. (In other words, state the facts in direct, declarative terms.) The purpose of documenting patient misbehaver in the medical record is to flag the issue for other providers treating the patient and to protect the urgent care center and its workers in case the patient’s behavior must be addressed in a more direct manner—such as by ejection from the facility and terminating care.

Documenting behavior in the medical record is especially important when treating VIP patients, as healthcare organizations often have different manners of providing care to them. Sometimes, VIP patients will be placed in more isolated parts of the unit and may even get to cherry-pick the providers who are assigned to their care—creating circumstances ripe for the type of abusive behavior that those in powerful positions may be accustomed to exhibiting. It is important for organizations to be mindful of the safety of providers when serving VIP patients.

Flexible Reassignment Rules and Provider Companion Arrangements

Another strategy is to encourage medical staff and physicians who are being sexually harassed by a patient to make a request to be reassigned to a different patient rather than “tough it out.” Such a policy should provide that requests will be granted whenever possible under the circumstances. The policy can specify that when circumstances do not make such a transfer possible, the harassing patient going forward will only receive care from the harassed provider when he or she is accompanied by a companion provider.

CONCLUSION

Sexual harassment in healthcare is a problem that needs to be better addressed. Medical providers face immense challenges and stress in their day-to-day jobs as it is. The fact that those challenges exist in a unique environment where inappropriate behavior of the type discussed here can fester unseen and unaddressed means it will continue to be a problem for all urgent care providers, operators, and patients—unless significant change occurs.

While the existence and enforcement of sexual harassment policies are important first steps, there is no employer sexual harassment policy that can completely fix this problem. Society must develop the ability to have nuanced public and private discussions about gender dynamics, sex, and power.

The Association of Medical Colleges reported that 2017 was the first time the majority of entering medical students were female.17 An increase in females having access to higher education and thus entering spaces traditionally occupied almost exclusively by men, along with a resulting generational shift in culture, hopefully will also move society toward creating a healthcare system in which healthcare workers have better protection and are not subjected to such destructive behavior and societal ills with such continuing frequency.

The bottom line for the urgent care operator is, unchecked sexual harassment of urgent care center staff (and physicians) by patients poses clear risks to employee wellbeing, patient care, and organizational integrity. It also has very real legal consequences for any urgent care center employer that fails to adequately respond and take appropriate action to address such incidents when it knows (or should know) patient sexual harassment is occurring.

Consistent, strong organizational responses to patient harassment will offer legal protection for the urgent care operator while giving workers confidence and a path for reprieve when repeatedly confronted with the scarring and abhorrent behavior that healthcare workers are likely to continue to confront and have had to endure for generations.

References

- Sholinsky S. #MeToo’s impact on sexual harassment law just beginning. Law360. October 14, 2018.

- 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(a)(1).

- Gurrieri V. Sex harassment claims jumped as #MeToo took off: EEOC. Law360. July 11, 2018.

- Grieco A. Scope and nature of sexual harassment in nursing. J Sex Research. 1987;23(2):261-266.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Notice number N-915-050. Available at: https://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/currentissues.html. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- Buckley-Norwood T. Sex harassment in health care in the wake of the renewed #MeToo movement and #TimesUp. AHLA Connections. July 2018.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Sexual Harassment. Available at: www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sexual_harassment.cfm. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v White (2006) 548 U.S. 53, 57.

- Phillips S, Schneider M. Sexual harassment of female doctors by patients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(6):1936-1939.

- (29 C.F.R. § 1604.11(e).

- Poe-Smith v Epic Health Servs. (D Del. 2017) 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 32907, 2017 WL 915139.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Southwest Virginia Community Health System to Pay $30,000 to Settle EEOC Sexual Harassment Suit. Available at:

https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/10-23-13b.cfm. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- Huston v Procter & Gamble Paper Prods. Corp. (3d Cir. 2009) 568 F.3d 100, 105 n.4

- Kunin v Sears Roebuck & Co. 175 F.3d 289, 294 (3d Cir. 1999).

- Ceglowski KM, Woodard DL. EEOC settlement reminds employers of responsibility to protect employees from harassment by third parties. Poyner Spruill. October 28, 2013. Available at: https://www.poynerspruill.com/Publications/EEOC-Settlement-Reminds-Employers-of-Responsibility-to-Protect-Employees-from-Harassment-by-Third-Parties. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- Campbell B. 3 tips to help protect workers from customer harassment. Law360. February 27, 2019.

- Chuck E. #MeToo in medicine: women, harassed in hospitals and operating rooms, await reckoning. NBC News. February 20, 2018. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/sexual-misconduct/harassed-hospitals-operating-rooms-women-medicine-await-their-metoo-moment-n846031. Accessed July 15, 2019.

1Suzanne C. Jones is a Shareholder at Buchalter, a law firm in Los Angeles. Roma B. Patel is an Associate at Buchalter. TEXT TO APPEAR AT THE END OF THE AUTHOR BLURBS: The authors thank research assistant Grace Bandeen for her invaluable assistance in producing this article.