Published on

Urgent message: As the debate rages as to whether today’s healthcare recipient should be regarded as a patient or a consumer, urgent care should consider which of the two mindsets will have the greatest positive impact on its care delivery model.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc is Chief Executive Officer of Velocity Urgent Care and is Practice Management Editor of The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine.

The advent of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) has shifted a greater financial burden onto the healthcare recipient. This and other cost-sharing mechanisms have combined to spur the growth of full-fledged consumerism in healthcare. Couple that with online and smartphone technology that’s elevating the consumer experience to unprecedented levels across most major industries, and you have a brand new landscape where formerly passive receivers of healthcare are empowered to expect transparency, comparison shop, and demand convenience and access at every touchpoint—the same way they do with their other service providers.

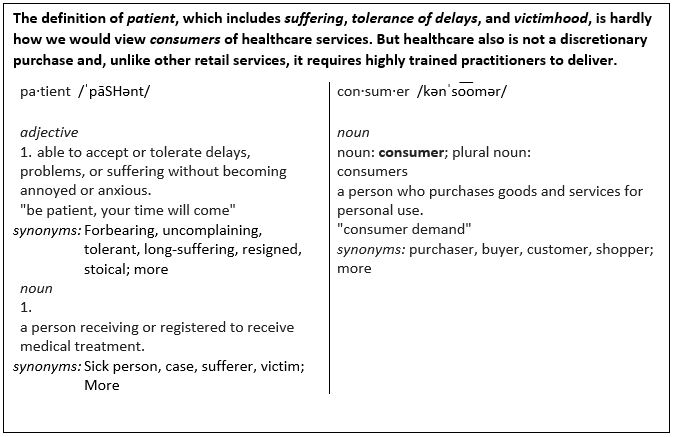

These developments have also spurred industry stakeholders to become engaged in a growing and important debate: Which is the appropriate nomenclature for today’s healthcare recipient—patient or consumer? And does it really matter? Whereas some see the debate as unnecessary and a mere question of semantics—like arguing the difference between “to-may-to” and “to-mah-to”—others feel strongly that the way you classify healthcare recipients will have a profound influence on the level and quality of care a healthcare entity delivers.

So where should urgent care stand on the debate? Should the retail-based urgent care model that places a premium on offering access and convenience sit on the “consumer” side of the fence? Or is it fundamentally important that any healthcare encounter—even those as brief and episodic as an urgent care visit—regard the recipient as a “patient” who implicitly entrusts the provider with their health and well-being, convenience aside? Here we’ll briefly examine several of the most oft-cited pros and cons of the patient vs consumer debate as they’re commonly expressed by healthcare leaders, patient advocates, and other industry stakeholders.

Pros of Patients

Technology and greater cost-sharing have changed consumer expectations (and behavior) toward healthcare providers in terms of access and convenience. Hence, the push for the label “consumer” could be seen as a call to arms for healthcare to adapt. Yet many providers regard the consumer label as transactional and impersonal, and thus inappropriate for the following additional reasons:

- The “consumer” model commoditizes healthcare services. Many physicians see the physician-patient partnership/relationship as an essential element to building the trust necessary to foster healing and deliver positive clinical outcomes. Treating the patient like a mere consumer as if healthcare services were simply another impersonal commodity erodes these principles, they feel, and undermines the sacred tenets that guide their practice.

- Healthcare is not a market; therefore patients aren’t consumers. In a market, pro-patient advocates assert, consumers are freely comparing products, services, prices, and features, and making the choice whether to make a purchase. Contrast that with, say, an emergency room setting, where nearly every patient shows up not because they want to be there, but because they’re most likely ill, injured, or in considerable pain—and seeking relief. Hardly the behavior of a “consumer,” patient advocates contend. Choice in this case has been effectively removed, with alleviation of pain and discomfort becoming the primary motivator. Even cost becomes a secondary consideration beyond relief, a cure, or abatement of suffering.

- Satisfaction with the service does not necessarily correlate with a positive clinical outcome. Urgent care operators are all too familiar with the following scenario: A misguided patient who does not need antibiotics (eg, for a common cold) demands them anyway. In this case, if the provider deems the person a “consumer” and this is strictly a business transaction, the provider may feel compelled to give them what they’re asking for, regardless if it’s the right thing to do or if it will negatively impact the clinical outcome. When the recipient is viewed as a “patient,” on the other hand, the provider may feel more empowered to do the right thing and deny the antibiotics (but counsel the patient why antibiotics are inappropriate for their presentation) since a “patient” is implicitly placing their trust in the professionalism, knowledge, and ethics of the physician charged with doing what’s best for their health.

Pros of Consumer

Today’s healthcare patient is informed, has options, and votes with their wallet—like a typical consumer. Healthcare leaders who therefore advocate for the “consumer” label believe organizations must adapt by first taking honest stock of these crucial shifts in the patient mindset towards that of a full-fledged consumer:

- Patients have become less tolerant of delays. Experience and anecdote have clearly shown us that people who utilize urgent care aren’t very tolerant of delays—in fact, delays are the #1 detractor to a centers’ Net Promoter Score. The correlation between likelihood to recommend the urgent care to others and how quickly a patient gets in/out of the center is stronger than any other element of the patient’s visit—including friendliness of the staff, competence of the provider, and the atmosphere of the physical facility. This is revealing, and clearly casts the urgent care user as less a patient, (in either sense of the word) and far more a consumer in most encounters.

- People are less forgiving of poor service. As technology helps improve the quality of service in other industries, patients, especially Millennials, are demanding the same from their healthcare providers. Thus, in order to capture the all-important patient loyalty that drives revenue, healthcare organizations must redesign their processes, operations, and delivery models as if they’re courting discerning, savvy consumers rather than patients concerned with just medical services and not satisfying, differentiated consumer experiences.

- The term “patient” implies passiveness. Healthcare leaders of today believe that rather than being reactive and simply following the doctor’s orders after illness/disease occurs, people must play an increasingly proactive role in their own health. Which is why some stakeholders are now avoiding the term patient, as they feel it implies passivity. In order to assume that active role that health leaders are imploring patients to accept, people must actively seek information about medical services, research options and alternatives, and compare quality, cost, access, and convenience across providers—like a consumer.

Conclusion

Should today’s healthcare recipient be regarded as a patient or a consumer? Perhaps the debate depends mostly on context. After all, when people are sick or in pain and need immediate treatment, they see themselves as patients who are entrusting the doctor to take charge and alleviate their discomfort. When they’re planning for a procedure or service and are in the comparison-shopping mindset, they tend to view things from the consumer lens. Hence, the goal of healthcare entities like urgent care should be to carefully study the issue, then design organizational process that best meet the needs of both mindsets: access, quality, and convenience on par with the industries that are spearheading the consumer revolution, while simultaneously encouraging and empowering the sacred physician─patient relationship/partnership that’s critical to patient health and well-being.