We live and practice medicine in a litigious society. How, then, can providers protect themselves against the threat of financial ruin due to malpractice payouts?

The first and most obvious answer is to not commit malpractice; more about that in a moment. The next most likely answer is for providers to purchase malpractice insurance with limits set high enough to protect their personal assets.

The median medical malpractice award tripled between 1997 and 2004. By 2004, the median award in a malpractice case was $440,000, and the average was $607,000. Today, approximately 5% of awards are over $1 million. Most physicians carry malpractice insurance which is capped at $1 million per claim and $3 million in aggregate per year.

When awards exceed that $1 million per claim cap, however, a physician’s personal assets are at risk. And once the threat of catastrophic loss is imminent, it is too late to move money to a safe asset. To that end, it is important to discuss asset protection with your financial advisor before those assets are at risk.

Back to solution number one (do not commit malpractice). How is it that some providers manage never to get sued? Clearly, some specialties are lower risk than others. Pathologists, physical medicine specialists, etc., generally skew towards the “better” end of the risk profile.

Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, urgent care physicians are in the middle of the risk profile. We don’t typically have long-term relationships with our patients or their families, we don’t respond to their calls in the middle of the night, and our interactions are often “one offs.” Moreover, many a serious medical problem starts as a trivial complaint which can be easily missed on first inspection. For example, a middle-aged woman with abdominal pain and a benign abdominal examine may evolve into a patient whose ischemic bowel took two or three visits to correctly diagnose. For now, let’s focus on how urgent care providers can protect themselves when the odds are stacked against them.

Slow and Steady Wins the Patient’s Trust

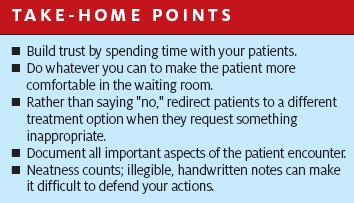

First and perhaps most obvious is to slow down and spend time with your patients. When a bad outcome is coupled with an interaction with a distracted, harried physician, the result is often litigation. Besides, the most satisfying part of our profession is the time we get to spend caring for others.

Consider the following scene as the patient might view it: Your waiting room is packed, the chairs are close together and uncomfortable, your staff is perceived as uncaring, and the magazines which depict all the things you do in your personal life—travel, fancy cars, and golf—are leftovers from your home. The final nail in the coffin is when the distracted, tired, and overwhelmed provider has one foot out the door during the encounter.

Sound familiar?

Although we recognize that in today’s healthcare milieu we are required to do more with less, the patient who is ill should not be forced to carry this burden. Do whatever you can to make the patient more comfortable in your waiting room. Educate your front office staff on customer service and communication skills. Introduce yourself on a first name basis (“Good afternoon; I am very sorry you had to wait to see me. My name is Jim Smith and I am happy to be your doctor.”) Shake the patient’s hand and sit down in a chair to listen to their story.

Many people who feel ill just want someone to listen to them and validate their concerns. At the end of the encounter, go over your treatment plan for them, allow them to ask questions, and tell them not to hesitate to return if they are not getting better or if they feel worse.

Say “No” without Saying “No”

If the patient demands something that you feel is not in their best interest, respond in the affirmative and redirect them to a different treatment option. Often, when patients hear the word “no” they tune out the rest of the message.

Consider, for example, a patient who is demanding Percocet because “that is the only thing” that has worked in the past even though his or her condition doesn’t warrant it. My response is usually, “You and I will definitely come up with a plan to treat your pain; however, it seems like Percocet has not been working for you in the past since you continue to require it for pain control….” In 20 years of practice, the technique of never saying “no” to patients has rarely been unsuccessful.

Document with Care

Another way to ward off malpractice suits is through thorough documentation. Charting is often done while running from room to room. What is charted is typically regarded as everything that was said and done. Things not charted are subject to speculation or memory lapse and are often viewed with suspicion by the plaintiff’s bar and jury. Take time to thoroughly document the important aspects of the history and physical.

Include the pertinent positives and negatives, as well as your thought process behind the diagnosis you made and the treatment plan you recommended.

For example, the chart of a patient who presents with the signs and symptoms of frontal sinusitis should reflect that consideration was given to the potentially fatal diagnosis of cavernous vein thrombosis (e.g., no diplopia, headache, or funduscopic signs of elevated ICP). It should also reflect that you considered meningitis or subarachnoid bleeding (history inconsistent with either diagnosis, along with normal mental status, no meningeal signs, etc.).

Illegible, handwritten notes and checkbox or template charting often give rise to documentation that is not defensible under the retrospective scrutiny of plaintiff’s experts. If your practice is using any variation of the aforementioned, take extra time to slow down and write legibly. Do not fall into the template “slash and check” mentality that fails to adequately tell the story of the encounter and provides you little protection against malpractice claims.