Urgent Message: Rural urgent care is the industry’s fastest growing segment, influenced by rural primary care shortages, hospital closures and extended ED wait times, but operational staffing and reimbursement complexities must be navigated.

Alan A. Ayers, MBA, MAcc

Citation: Ayers A. Rural Urgent Care Grows, But Challenges Remain. J Urgent Care Med. 2024; 19(3): 17-21

As access to care in rural areas continues to decline, urgent care (UC) can play a pivotal role in the market to fill that gap. Many rural hospitals are facing financial strain as well as pressure to consolidate with larger urban healthcare systems, while the need for accessible alternatives such as urgent care is greater than ever.1

Today, rural UC is the fastest-growing and perhaps most operationally complex of all geographic segments—a fact previously outlined in the December 2019 edition of JUCM.2 Understanding the underlying dynamics of rural healthcare provides essential context that may help UC operators successfully navigate expansion into these underserved areas.

Fastest-Growing Segment of Urgent Care

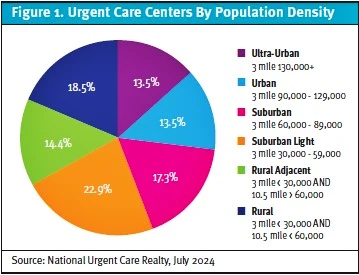

When considering localities, “rural” areas (in which fewer than 30,000 people live in a 3-mile radius, and fewer than 60,000 people live in a 10-mile radius) and “rural adjacent” areas (in which fewer than 30,000 people live in a 3-mile radius, but more than 60,000 live in a 10-mile radius) collectively comprise 32% of all UC centers, according to National Urgent Care Realty (Figure 1). The rural segments are second only to “suburban” settings (areas in which 60,000 to 89,000 people live in a 3-mile radius).

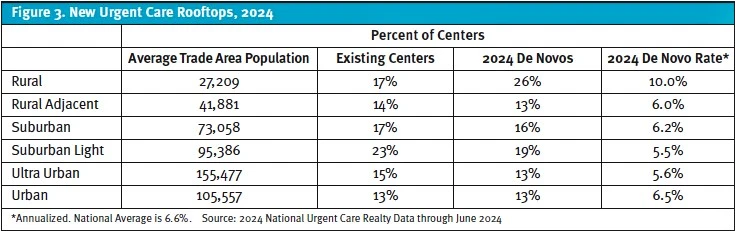

Rural UC is an enticing go-to-market strategy, and data from National Urgent Care Realty reveals the 10 largest non-hospital operators that are embracing this approach (Figure 2). Notably, the data also shows that rural UC is the fastest-growing segment among all settings, accounting for 26% of new rooftops in 2024 (Figure 3). Overall this year, rural UC is adding rooftops 40% faster than suburban areas through June 2024, while urban growth is flat. Despite this surge, forecasts suggest that 2025 will see a modest slowdown in the rural segment as urban growth accelerates (Figure 4).

Rural America’s Access Crisis

Over the past decade, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed, leaving residents with fewer options for care.3 Beyond that, more than 700 rural hospitals currently are at risk of closing because of serious financial distress, according to the Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform.3

A separate study by health analytics and consulting firm Chartis found that half of rural hospitals in the United States lost money last year—an increase from 43% the year prior.1 This trend disproportionately affects states like West Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Ohio, where between one-third and one-half of rural hospitals are at risk of closing.1

As urban health systems expand their reach and pull resources away from small community hospitals, the access imbalance grows. Larger health systems have acquired many rural hospitals in recent years, and the effect the transactions have had on quality, services, prices, or closure of clinical specialties remains unclear, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.4

Rather than offering a full slate of services in rural communities, urban healthcare networks tend to focus on primary care outposts that can refer rural patients to urban locations for specialty care when needed. In West Virginia, for example, the specialty needs of large segments of the population are served by academic medical centers 3-4 hours away in Columbus, Ohio. The distance may create hardship for families in terms of transportation, child care, and time off work, for example.

As urban healthcare networks grow, their rural community counterparts may have fewer strategic options for timely, comprehensive care. Telemedicine is often touted as a solution, but many health services require in-person visits, especially for urgent needs.

For urgent care developers, the widening gap between urban and rural healthcare presents an opportunity. By establishing new UC centers in rural areas, it’s possible to fill some of the void left by struggling or shuttered community hospitals. Providing essential services and reducing residents’ need to travel long distances positions urgent care as a cornerstone of healthcare delivery in these underserved areas.

Challenges for Rural Urgent Care

While rural UC is well-positioned to fill a crucial healthcare gap, staffing shortages—particularly for x-ray technicians—and the loss of scale economies are among the major operational obstacles.

For example, Ohio law mandates that x-rays may only be captured by a certified radiology technologist (RT) or a general x-ray machine operator (GXMO). RTs hold an associate’s degree and must pass an American Registry of Radiologic Technologists exam. With typical centers performing as few as 3 x-rays per day, RTs might be expected to take on medical assisting or administrative tasks, making urgent care a less attractive career setting for them. Ohio GXMOs, meanwhile, must work under the direct supervision of an on-site physician. Yet, over 85% of urgent care visits today are delivered in a center that doesn’t have a physician routinely present, limiting the options for GXMOs, thus reducing the availability of x-ray services.

One-third of rural counties in Ohio lack access to after-hours x-ray services outside of emergency departments (EDs), so an urgent care that is able to provide x-rays after-hours would be an important resource that offers value to the community (Figure 5). Rural urgent care centers across the United States could help address not only everyday access issues if adequately staffed but also the after-hours access challenges as well.

Rural urgent care started gaining traction in Southeastern states like Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia before expanding through Kentucky, Indiana, and the Midwest. As the market growth moves westward into Texas and beyond, scale economies become more challenging to maintain in states with larger geographic spreads of rural landscapes.

In states like Ohio and South Carolina, county seats are typically 30 to 45 minutes apart, which enables sharing of staff and makes staffing urgent care centers from the suburbs of larger cities like Columbus or Charlotte feasible. However, in regions like West Texas and the Great Plains, towns can be 100 miles apart, making it especially difficult to ask staff to travel that far to cover resource shortages among other centers in the network. Without the benefit of a regional staffing pool, these more remote centers are vulnerable to unexpected closures when key staff members are unavailable due to turnover, illness, or paid time-off. This loss of scale makes rural urgent care operations riskier as the model moves into more sparsely populated regions.

Higher Reimbursement With a Catch

According to Experity data, 83% of urgent care centers bill as Place of Service 20 (POS 20, urgent care center), 11% bill as POS 11 (primary care provider office), and just 2% bill as POS 72 (rural health clinic). Although an urgent care center in a rural area can be contracted and bill as any of the 3, only a federally designated Rural Health Clinic (RHC) may bill its services under POS 72.

The RHC designation can offer adjusted revenue for clinics in underserved rural areas—albeit with a few drawbacks. Along with completing an on-site inspection, which requires adherence to operational standards, organizational functions, and processes, to qualify for RHC status, a clinic must be:

- Located in a state-designated Medically Underserved Area

- Owned by a provider or provider entity

- Staffed by nurse practitioners or physician assistants more than 50% of the time

- Intended as access for Medicare and Medicaid patients (but can still see commercial populations)5

A Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) policy enacted in 2021 gradually increases per-visit Medicare rates for RHCs from $100 in 2021 to $139 in 2024, eventually reaching $190 in 2028. While this promise of increasing reimbursement may be enticing, it has several important caveats.

The RHC reimbursement is effectually an all-inclusive rate, but it also functions like a cost-plus model from the standpoint that Medicare reimbursement is determined by a cost report—a summary of allowable expenses that must be filed by the provider annually.

Unlike private insurance “case rates,” the cost report does enable the RHC to recapture some losses due to bad debt and the added costs of preventive care and wellness screenings typically not reimbursed in UC. Even so, withholds and claw-backs can occur. Because payment is the lesser of actual cost or the CMS rate (the “limit”), many RHCs actually lose money on Medicare patients.

The challenges associated with RHC designation include:

- Complex billing requirements: RHCs must handle split billing on UB04 forms for RHC services and CMS1500 for commercial claims, increasing the administrative workload.

- Upgraded point-of-care lab capabilities: Clinics must invest in upgraded lab equipment to perform “moderately complex” tests on-site, such as metabolic panels, which can be a significant financial burden not just in start-up costs but also in ongoing maintenance.

- Cost reporting and reconciliation: RHC reimbursement is tied to the clinic’s annual cost report. While this allows clinics to recapture some costs related to bad debt and added preventive care, it doesn’t guarantee financial sustainability or surplus.

For urgent care centers—where volume and efficiency have long been the key to profitability—the RHC model presents a paradox. Considering 85% of costs (including labor) are fixed, profits in UC are driven by throughput and efficiency. By contrast, RHC cost reconciliation disincentivizes high efficiency and throughput, instead rewarding cost maximization to reach the prescribed limit.

Urgent care owners must be diligent about these factors and the associated billing complexities to ensure financial stability (Figure 6).

ED Wait Times Drive UC Volume

An analysis conducted for JUCM recently found that nearby hospitals can have an impact on rural UC performance. Urgent Care Consultants experts examined a sample of 93 urgent care centers across 4 primarily rural states. They compared 2023 urgent care metrics from Experity EMR data (visit volume, visit time length, net promoter score, and average patient age) to published CMS data for the nearest hospital ED. Psychiatric hospitals, children’s hospitals, and specialty facilities were eliminated from the dataset, and the next-closest general hospital was considered.

The average wait time in the ED was the most significant correlation in the data. When patients have an extended wait time in the ED, they are more likely to leave and seek care elsewhere. What the data analysis revealed in effect is that when the ED length of stay was longer, the incidence of patients leaving the ED without being seen was higher, and when an urgent care center was close by, those urgent cares saw greater patient volumes. Notably, while ED wait time was the greatest driver of patients leaving without being seen, distance to the nearest urgent care was the second most impactful factor.

Practical Implications for Urgent Care

There are many factors to assess for UC operators considering rural site selection. RHC eligibility, staffing availability, and ED wait times at nearby hospitals significantly influence a center’s prospects for success.

The continued growth of rural urgent care will be a function of the risks and opportunities within rural healthcare markets. In addition, growth could easily reach a tipping point as rural locations inch closer to saturation. By focusing on efficient operations, strategic site selection, and local healthcare dynamics, rural urgent care centers can thrive in today’s evolving healthcare landscape.

References

- Chartis website. Unrelenting Pressure Pushes Rural Safety Net Crisis into Uncharted Territory. February 15, 2024. Accessed at: https://www.chartis.com/sites/default/files/documents/chartis_rural_study_pressure_pushes_rural_safety_net_crisis_into_uncharted_territory_feb_15_2024_fnl.pdf.

- Ayers A. Rural and Tertiary Markets: The Next Urgent Care Frontier. J Urgent Care Med. 2019;14(3):34-39. Accessed at: https://www.jucm.com/rural-and-tertiary-markets-the-next-urgent-care-frontier/.

- 3. Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform website. Rural Hospitals at Risk of Closing. July 2024. Accessed at https://chqpr.org/downloads/Rural_Hospitals_at_Risk_of_Closing.pdf

- Kaiser Family Foundation website. Ten Things to Know About Consolidation in Health Care Provider Markets. April 19, 2024. Accessed at: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/ten-things-to-know-about-consolidation-in-health-care-provider-markets/

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. State Operations Manual Appendix G – Guidance for Surveyors: Rural Health Clinics (RHCs). June 7, 2024. Accessed at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/appendix-g-state-operations-manual.

Download the Article PDF: Rural Urgent Care Growth Continues, But Challenges Remain