Published on

After the vivid video of the wrongful death of George Floyd went viral in late May, millions of people of all races in America and abroad took to the streets to demonstrate in the name of solidarity and justice. This was all motivated by one man’s story and, more broadly, was a potent remind of the power of story to capture our attention and provoke action.

George Floyd was the most recent widely publicized victim of unwarranted police violence against people of color in the U.S. Within hours of his death, demonstrations began throughout country. But why did his death serve to galvanize the public so much more dramatically than did the deaths of Breonna Taylor, Laquan McDonald, and countless others who met similar brutality?

Consider President Kennedy’s famous June 1963 speech later referred to as his “civil rights address.” Until the speech, delivered over 2 years after taking office, he had remained relatively silent on the topic of civil rights. So what inspired Kennedy to finally speak up after ignoring the violence for so long? Many political historians site this as a response to the iconic images from the then-recent protests in Birmingham, AL which were seen by millions of Americans. The photographs and footage of encounters between law enforcement and demonstrators were dramatic in their imagery. The public saw German shepherd police dogs biting terrified protestors and firehoses turned against peaceful African-American teenagers.1

Both the public response to the death of George Floyd and President Kennedy’s hand being forced to finally acknowledge systemic racism due to the violence in Birmingham came after many years of similar tragedies which failed to provoke such responses.

The main distinction shared by both these cases was the explicitness with which the media-consuming public was shown the needless suffering of nonviolent and helpless African-Americans. We didn’t hear about the details from the lips of a newscaster with meticulously combed hair. We saw children dropped to their knees with blasts of water and we watched Floyd get killed, face down on the street, gasping for air, with our own eyes. There was no ambiguity about who was wronged and who was perpetrating the harm. These were easy stories to follow and we were deeply affected by them.

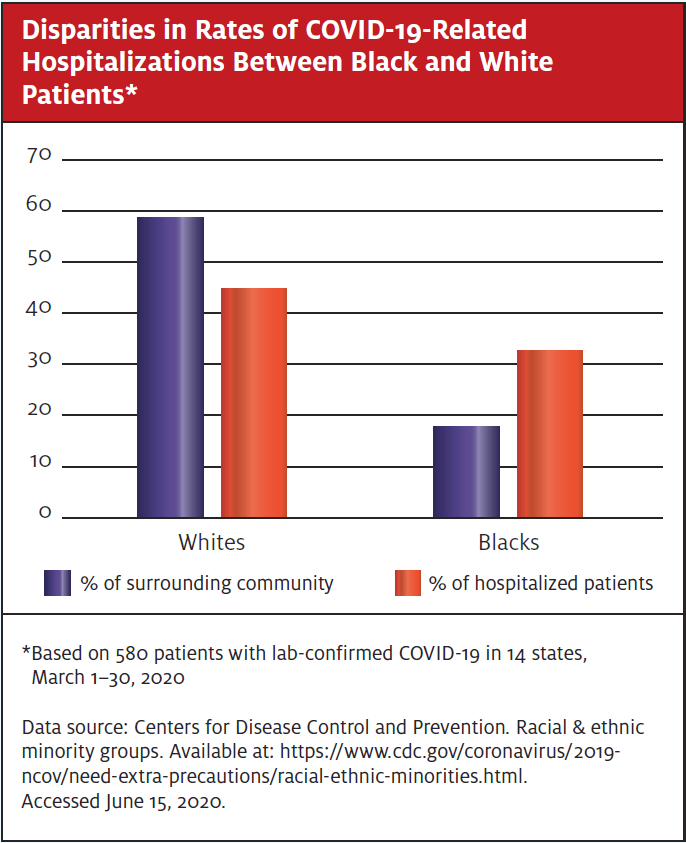

Compare this with the current coronavirus pandemic. Disparities in outcomes based on race among those afflicted with the virus are stark and undeniable. African-Americans and other underrepresented minorities have long fared worse in many measures of health such as rates of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. And, tragically, this has also proven true in the case of mortality associated with COVID-19.

African-Americans have comprised 40% of the deaths related to the virus in the state of Michigan, but only make up 14% of the population, for example.2 Similarly, in Chicago, 70% of COVID-19 related deaths have occurred in blacks, who represent just 30% of the city’s residents. In New York, the city most severely afflicted by the virus, both blacks and Hispanics have faced a disproportionately high burden of mortality.3

These differences in outcomes cannot conceivably be explained by biological factors. Rather, it has become clear that such discrepancies are related to the implications of race as a social construct. Race, in turn, is highly correlated with factors that have been dubbed the social determinants of health (SDOH)—eg, food insecurity, poverty, unstable housing, access to healthcare and education., and neighborhood environment.4

Meanwhile, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease—all of which underrepresented minorities experience in disproportionate numbers due to SDOH—have been identified as risk factors for increased COVID-19-related mortality.5 Furthermore, chronic stress has been repeatedly demonstrated to be immunosuppressive.6 And stress is understandably a natural byproduct of the day-to-day experience of for many blacks and Hispanics in America.

If you have been following news of the pandemic, this is undoubtedly not the first time you’ve heard of these dramatic differences in outcomes. Both the medical literature and popular press are replete with reports of COVID-19 ravaging Hispanic and African-American communities. Yet neither the lay pubic nor the medical community at large has reacted to this with the same sort of rallying cry as with the case of George Floyd. How did injustice leading to the loss of one man’s life inspire so many more to take action than the coinciding deaths of many thousands, largely due to the same systemic injustice?

The difference lies in how the narratives are presented—story vs data. Stories grab our attention and compel us to act. Data do not.

As clinicians, we make decisions about how to evaluate and treat our patients based on rigorously analyzed (and often meta-analyzed) data. However, because we are in the habit of thinking in terms of sensitivities and specificities, all too often we resort to attempting to persuade others using data-driven arguments. And while this can occasionally be appropriate—when discussing treatment options with a particularly analytically minded patient, for instance—if we seek to inspire any sort of behavior change, story is a much more effective tool. In fact, that’s one of the most fundamental attributes of a story: it evokes and demands an immediate response.

As human beings, we are wired for story. We think in story. We understand the world through story. We are moved by story. Neuroscientists have long discussed the duality of the rational and emotional brain; however, it is almost exclusively the emotional brain which compels us to act. And story is a direct conduit to these emotional centers of our brains.

This notion is simple yet powerful. And, as healthcare providers, we have an obligation to advocate for the health of our patients, much of which is influenced by persistent racial inequality and its effects on the SDOH.

If we are to serve as allies for those facing health disparities due to race, speaking in statistics is unlikely to capture more than momentary attention, much less inspire action. However, the more we can share individual patients’ stories (in a HIPAA-compliant fashion, obviously), the more we can evoke a passion among those who will listen to speak out and take a stand against this pernicious, but sadly less cinematic injustice.

The more vivid the account, the more powerful the effect will be. People will take notice. More allies will emerge. And, in the process of learning more of these stories, we may find we are inspired ourselves to go further for such causes in new and surprising ways. Because, after all, we are humans first and we cannot help but respond to a powerful story.

If you have a story, clinical or otherwise, about the effects of racial injustice on a patient you have served, please consider submitting the narrative to JUCM. (Submission instructions can be found at https://jucm.scholasticahq.com/for-authors.) We would love to share it with the urgent care community.

References

- Rieder J. The day President Kennedy embraced civil rights—and the story behind it. The Atlantic. June 12, 2013. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/06/the-day-president-kennedy-embraced-civil-rights-and-the-story-behind-it/276749/. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- Malcolm K, Sawani J. Racial disparities in the time of COVID-19. Michigan Medicine. Available at: https://labblog.uofmhealth.org/rounds/racial-disparities-time-of-covid-19. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. 2020;323(19):1891–1892.

- Paeratakul S, Lovejoy J, Ryan D, et al. The relation of gender, race and socioeconomic status to obesity and obesity comorbidities in a sample of US adults. Int J Obes2002;26:1205–1210.

- Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;m1985.

- Dhabhar FS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress on immune function: implications for immunoprotection versus immunopathology. All Asth Clin Immun. 2008;4(1):2-11.