Urgent message: The ability to evaluate children presenting with a limp—and to recognize red flags that help distinguish those to treat from those requiring immediate referral—should be within the purview of the urgent care clinician.

Raymond W. Liu, MD, Hadeel Abaza, MD, and Allison Gilmore, MD

A limping child without a clear traumatic history or diagnosis is a common presentation to an urgent care center. The broad differential diagnosis can be daunting, with causes that range from relatively benign conditions or injuries to those requiring emergent care.

A careful history and physical exam, in conjunction with an understanding of the age relationship of many diagnoses, can narrow the differential dramatically and inform the decision to treat or refer as needed.

This article will provide a framework for evaluating limping children in the urgent care center, with an emphasis on preventing potentially catastrophic outcomes.

Types of Gait

While determining type of gait is ideal, this is probably beyond the scope of training of the typical urgent care practitioner. Therefore, recent changes in gait should be determined whenever possible, whether identified by direct questioning of the patient or reported by the caregiver.

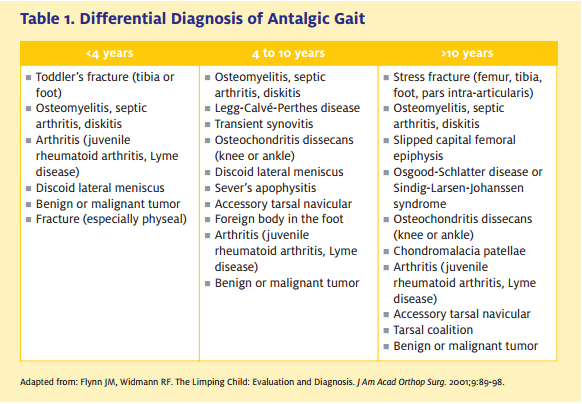

Antalgic gait is the most common gait type seen, resulting from pain in any part of the lower extremity or the back. It is characterized by a shortened stance phase on the affected side, with a resultant increase in the swing phase. In more severe cases, the child refuses any weight bearing. Differential diagnosis of antalgic gait may be categorized according to the patient’s age (Table 1).

Other, less common, gaits categorized as nonantalgic are beyond the scope of this article.

Patient History

Typically, the history taken from a child is incomplete and supplementation from the caregivers can be helpful.

Any associated trauma should be delineated. If pain is present, it is important to document its location, frequency, duration, and timing.

Acute pain suggests trauma, infection, or malignancy whereas gradually worsening pain can be inflammatory or mechanical.

e child lying down, evaluate for any asymmetry and areas of swelling and erythema. When possible, try to determine the point of maximal tenderness; this localizes the site for imaging and possible aspiration. If the exam is limited by clothing, the child should change into a hospital gown.

e child lying down, evaluate for any asymmetry and areas of swelling and erythema. When possible, try to determine the point of maximal tenderness; this localizes the site for imaging and possible aspiration. If the exam is limited by clothing, the child should change into a hospital gown.

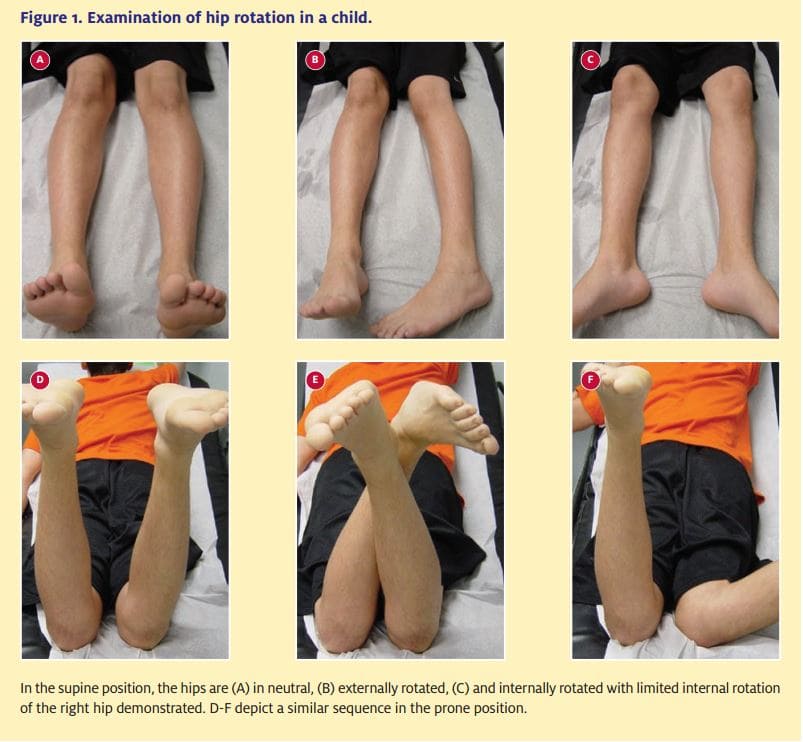

The bilateral hips, knees, and ankles should be taken through range of motion (Figure 1) to observe the following:

- A hip that is held in a flexed and externally rotated position raises concern of a septic joint; as such, emergent referral is indicated.

- A decrease in internal rotation of the hip suggests pathology.

- The plantar feet in ambulators and the shins in crawlers should be carefully examined for injuries or foreign bodies.

- A positive FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation of hip) may suggest sacroiliac pathology.

- In addition, the patellofemoral joint should be examined in cases of adolescent knee pain.

Imaging

When the site of concern can be localized by swelling or tenderness, plain radiographs in orthogonal views should be obtained. If images cannot be obtained in the urgent care setting, referral to the ED or orthopaedist is indicated.

For any bony injury, the joint above and below should be included in the imaging. In addition, the urgent care provider should be aware that certain conditions (e.g., intra-abdominal issues presenting with limp/gait disturbances) may masquerade as bony injuries, thus increasing the risk of drawing erroneous conclusions.

In younger children where a site of concern cannot be identified, the entire lower extremity should be imaged.

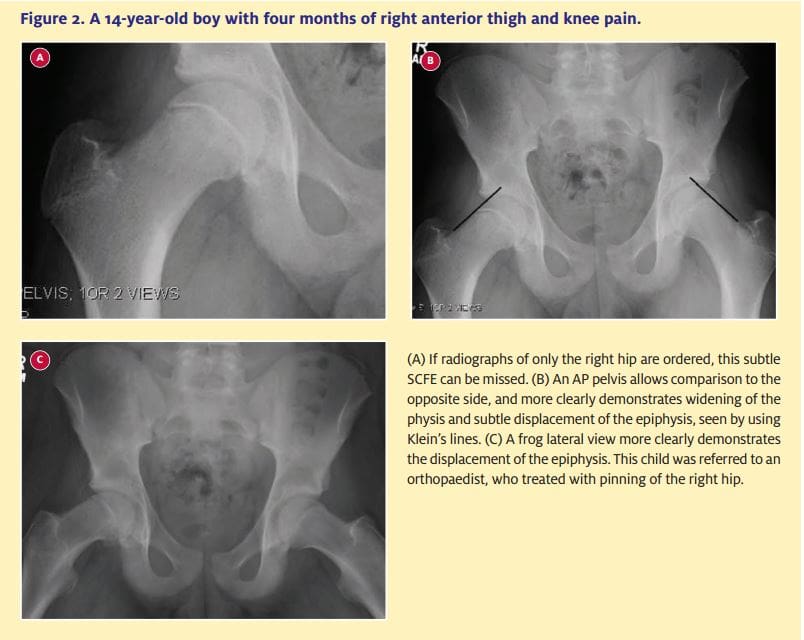

For a child requiring radiographs of the hip, obtaining anterior-posterior (AP) and frog lateral views of the pelvis is preferable to unilateral hip films, since it allows comparison with the normal side (Figures 2A and 2B).

In early osteomyelitis or septic arthritis, radiographs most commonly appear normal.

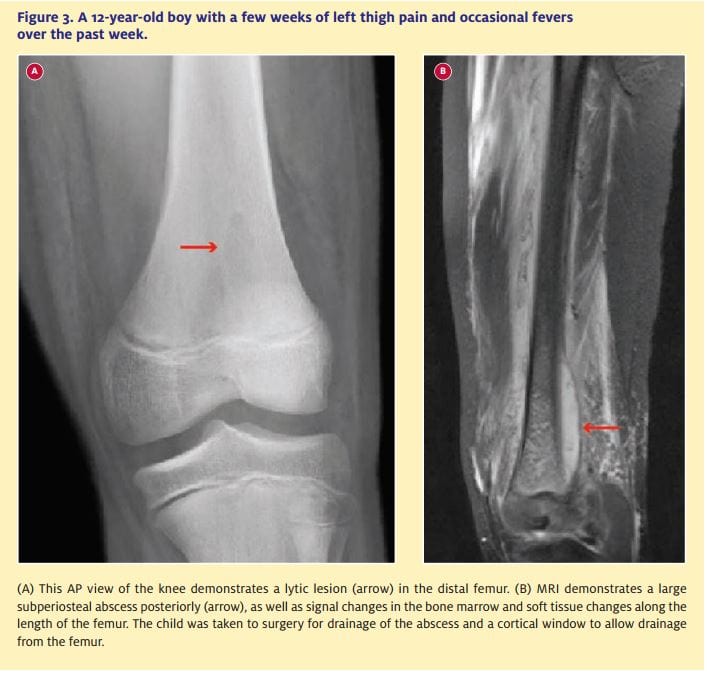

The earliest radiograph finding in osteomyelitis is local soft tissue swelling, which may occur within three days, rather than seven days for the earliest bony changes (Figure 3).

Radiographs in septic arthritis may demonstrate >2 mm of hip joint space widening; in one study, a displaced or blurred fat pad was seen in all cases of septic arthritis.1

Ultrasound can be useful in children where septic hip infection is a concern. A 5% rate of false negative results has been reported for early septic arthritis;2 thus, children in whom there is a clinical suspicion should be referred for

close observation or aspiration.

If an effusion is discovered, often the same radiologist can perform a diagnostic aspiration under ultrasound guidance. If clinical suspicion is high, then operative treatment should be not delayed for either an ultrasound or an ultrasound guided aspiration.

Ultrasound can also be useful in diagnosing osteomyelitis and detecting a subperiosteal abscess.

Bone scan has a low sensitivity for joint infection, but can be useful for detecting osteomyelitis, especially in cases of the pelvis and spine where the infectious site may not be well localized. However, the availability and time requirements for bone scan typically preclude its use in the urgent care center.

Advanced imaging is usually best directed by an orthopaedic consulting team. Computed tomography (CT) scans can be useful when cortical changes are seen on radiographs, and for diagnosing an osteoid osteoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are more useful for soft tissue changes, abscesses, stress fractures, and most tumors (Figure 3).

Laboratory Tests

Whenever infection is a concern, test for white blood cell (WBC) count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP). If such tests cannot be performed in the urgent care clinic, emergent referral is indicated.

Although WBC can be normal in bone and joint infections, an increase in neutrophils on the differential is more sensitive.

Huttenlocher and Newman reported that an ESR >50 mm/h with a new onset limp was associated with a clinically important diagnosis in 77% of children,3 while Scott et al found an elevated ESR in 91% of patients with osteomyelitis.4 CRP can be more useful in an acute time period, and can increase within six hours of disease onset. In appropriate geographical regions, a Lyme titer should also be considered.

If there is clinical concern for a septic joint, then an aspiration is warranted. A WBC >50,000/L or >75% polymorphonuclear cells is suggestive of infection.

Conditions in All Age Groups

Transient synovitis

Transient synovitis is the most common cause of acute hip pain in children between 3 and 10 years of age.

The postulated mechanism is an inflammatory joint reaction to a viral or bacterial infection occurring elsewhere in the body, although this remains unproven. Parents often report an upper respiratory or ear infection one to two weeks earlier, and children complain of unilateral hip or groin pain.

Typically, patients lack any significant fever or systemic illness. The examiner will be able to obtain some passive range of motion of the joint, and the child is usually able to bear some amount of weight. Laboratory tests and radiographs tend to be normal.

Treatment is symptomatic, with symptoms usually resolving within 48 hours.

Septic arthritis

Septic arthritis can have a similar presentation to transient synovitis, and it is often difficult to clinically differentiate between the two. However, with septic arthritis the child usually refuses to bear weight and does not allow range of motion of the hip, tending to hold the hip in flexion and external rotation; this allows maximum volume within the hip joint. Lab

studies are elevated

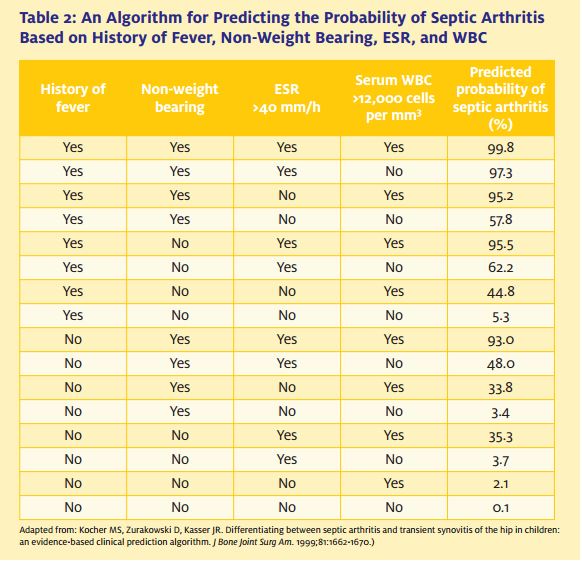

Kocher et al found that a child with at least three out of four predictors (fever >38.5oC, refusal to bear weight, ESR >40 mm/h, and WBC >12,000/L) had a 93% or higher probability of septic arthritis (Table 2).5

Blood cultures are positive

in 50%, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most common organism. Radiographs do not demonstrate bony changes until seven days or more, though ultrasound can demonstrate a joint effusion more acutely.

Septic arthritis is ruled out by aspiration, with WBC typically ranging from 80,000/L to 200,000/L. Antibiotics should be delayed until aspiration or surgical drainage to aid in future antibiotic therapy. Treatment is emergent surgical irrigation, in order to prevent irreversible cartilage damage.

In certain geographical regions, Lyme disease should be considered. Lyme disease most commonly affects the knee, one to two joints, and peaks at age 7.

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis in children occurs most commonly via hematogenous spread to the relatively static blood supply in the metaphysis. When it occurs in isolation, the clinical presentation is often more mild than that seen with septic arthritis. Often, the child can ambulate, though with an antalgic gait.

Careful palpation may reveal maximal tenderness over the metaphyseal region of the bone. Passive range of motion may be limited, though not as dramatically as in a septic joint.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a bone scan or MRI.

Antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment in isolated osteomyelitis. In children with sickle cell anemia, Salmonella should be considered.

Osteomyelitis can be associated with a subperiosteal abscess or a septic joint. An abscess forms when the magnitude of the bone infection generates excessive pressure. Abscesses are diagnosed by ultrasound, MRI, or direct aspiration as preferred by the orthopaedics consulting team.

Treatment is surgical irrigation and windowing of the cortex to relieve pressure. Again, antibiotics should be withheld until an aspiration or surgical culture is obtained.

In the proximal femur, distal tibial, proximal humerus, and proximal radius the metaphysis is intraarticular, and thus these joints are susceptible to a combined osteomyelitis and septic arthritis.

Children tend to present with a more severe septic arthritis picture; treatment is surgical irrigation and a possible cortical window.

Diskitis

Diskitis is inflammation of the disk space, often due to infection.

Incidence peaks at age 7. Children present with sudden-onset back pain, refusal to walk, irritability, and sometimes fever. Parents may report that when bending over, toddlers keep their spines straight and bend through the knees and hips. The child often looks unwell, but neurological exam is generally normal.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism; due to this and the location of the infection, antibiotics may be administered without obtaining an aspiration.

Radiographs can be negative for the first few weeks, and can show disk space narrowing and erosion of the end plates. MRI confirms the diagnosis acutely and can evaluate for an abscess, which would necessitate surgical drainage.

Treatment is intravenous antibiotics. If a child does not respond to antibiotics, a more uncommon organism should be suspected.

Leukemia

Leukemia peaks at ages 2-5 years. Children can present initially with musculoskeletal pain.

Laboratory tests demonstrate an increased ESR and WBC, and a decreased hematocrit. Physical examination may demonstrate lymphadenopathy and/or hepatosplenomegaly, and patients can have a low-grade temperature.

Radiographs and bone scan are usually negative, though radiographs may show osteoporosis or metaphyseal bands.

Suspicion of leukemia warrants an oncology consult.

Pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

Pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis peaks at age 2, and occurs more commonly in females. Larger joints are more likely to be affected.

Patients present with pain, limp, joint swelling, stiffness, erythema, warmth, and fever.

Laboratory studies are often normal, though an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test is positive in half of patients.

Treatment can be managed through an outpatient rheumatology clinic.

Conditions in Toddlers (Ages 1-3 Years)

Toddlers can present diagnostic challenges, due to their inability to effectively verbalize complaints. Normal gait in a toddler is wide based, with increased hip and knee flexion and increased cadence. Gait sometimes needs to be visualized at a distance due to the toddler’s anxiety

Toddlers’ fractures

“Toddlers’ fractures” often present with a history lacking any remarkable traumatic event. Affected toddlers—often new walkers—present with difficulty or refusal to bear weight.

Careful and systematic palpation may reveal maximal tenderness over the tibial shaft, which is the most common site of a toddler’s fracture. Radiographs can be very subtle.

Any child with a suspected fracture should be splinted, with plans for follow-up radiographs with an orthopaedist in seven to 10 days to look for periosteal new bone formation.

Developmental dysplasia

Aside from the infectious and traumatic concerns already discussed, most presentations of limping toddlers are nonurgent and can be treated on an outpatient basis, either in the urgent care setting or in the ED.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip can present with Trendelenburg gait when unilateral, or waddling gait when bilateral. Be vigilant for the classic “4 Fs” (female child, first born, frank breech, and family history). The physical exam may reveal asymmetric skin folds, extremity shortening, and limited hip abduction. Plain films demonstrate a shallow acetabulum, with or without

subluxation or dislocation of the femoral head.

Patients should be seen by a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon within one to two weeks.

Cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy presents with a spastic gait due to muscle imbalance. Parents may report toe-walking, dragging the leg, or limping.

Examination may reveal spasticity, limited range of motion, hyperreflexia, and clonus.

The toddler should be referred to a pediatric neurologist and pediatric orthopaedist.

Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy presents with progressive proximal muscle weakness, with the main types being the severe Duchenne and mild Becker types.

Evaluation may reveal a Trendelenburg gait due to weak hip abductors, a Gower’s sign where the toddlers “walk” up their legs using their arms due to proximal weakness, and pseudohypertrophy of the calves.

These toddlers should be referred to a pediatric neurologist.

SCFE in an adolescent requires emergent surgery and non-weight bearing on the affected hip.

Conditions in the Child (Ages 4-10 Years)

Older children are better able to provide a patient history and, generally, do not have secondary gain. Parents should be questioned about recent growth spurts, as growing pains are a common cause in this age group.

Physeal fractures/Salter-Harris I fractures

Physeal fractures are more common in older children. Salter-Harris I fractures, which are fractures through the growth plate only, can be difficult to diagnose on radiographs if they are nondisplaced.

If a child has a history of trauma, and examination demonstrates tenderness in the region of the growth plate, then the extremity should be immobilized with a splint even with negative radiographs.

Follow-up radiographs with an orthopaedist in one to two weeks will demonstrate periosteal new bone formation if a physeal fracture did occur.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease is avascular necrosis of the femoral head, typically in children ages 4-8 years. It is more common in males than in females, by a ratio of approximately 4:1.

Initially, children present with a painless limp, although with time pain can develop.

Examination demonstrates limited range of motion and an antalgic gait. AP and frog lateral radiographs of the pelvis should be ordered, and may demonstrate subchondral sclerosis, subchondral fracture, or flattening of the femoral head, though they may remain negative early in the disease.

Children should follow up with a pediatric orthopaedist within a few weeks.

Patients with pain should be placed on limited activities until their symptoms resolve.

Discoid lateral meniscus

A discoid lateral meniscus often affects children at between 8 and 12 years of age. History reveals limping, knee swelling, painful clicking, and decreased range of motion in extension.

Symptoms are exacerbated with activity.

Examination demonstrates lateral joint-line tenderness, knee effusion, and painful clicking in the knee. Radiographs may be normal, or may show a wide lateral joint space, a flat lateral femoral condyle, and cupping of the lateral tibial plateau. Diagnosis is confirmed with MRI.

Patients should follow up with an orthopaedist.

Leg length discrepancies

Leg length discrepancies can present as a limp in the urgent care center. Typically, these become apparent between the ages of 4 and 10 years. Patients may present with a toe-walking or vaulting gait.

Examination is best done by placing blocks under the shorter limb and feeling the iliac crests to determine whether the pelvis is level. Arthrograms and scanograms are specialized radiographs that are best performed through a pediatric orthopaedic clinic.

Conditions in the Adolescent (Ages 11-16 Years)

Adolescents can provide a complete history, but may overstate or understate symptoms for secondary gain. Occasionally, they should be questioned separately from their parents (for example, to obtain a sexual history when gonococcal infection is suspected).

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is displacement of the proximal femoral epiphysis from the metaphysis. It is more common in obese, African-American males, generally between ages 12 and 15 years.

Adolescents with SCFE present with a limp and pain in the groin, or referred pain to the inner thigh or medial knee. An endocrine work-up should be considered for girls

Examination demonstrates painful range of motion of the hip, with limited internal rotation and obligate external rotation of the hip when it is passively flexed. AP and frog lateral radiographs of the pelvis demonstrate displacement of the epiphysis (Figure 2). Klein’s line is drawn along the lateral border of the femoral neck, and should pass through the epiphysis in a normal femur.

SCFE in an adolescent requires emergent surgery and non-weight bearing on the affected hip to avoid further displacement and the catastrophic development of avascular necrosis.

Osteochondral defects

Osteochondral defects most commonly affect the lateral portion of the medial femoral condyle.

Patients typically present with knee pain, occasionally with mechanical symptoms such as popping or locking. The lesion can often be seen on radiographs, but may require an MRI for diagnosis.

Management varies, depending on patient age and the characteristics of the lesion. Patients should be given crutches and placed on protective weight bearing and instructed to see an orthopaedist.

Overuse syndromes

Overuse syndromes are common causes for knee pain in adolescents.

Osgood-Schlatter disease is overuse at the tibial tubercle apophysis. Physical examination demonstrates point tenderness at the apophysis, and radiographs may show fragmentation of the tibial tubercle. Overuse can also occur in the patellar tendon and at the inferior pole of the patella.

Treatment consists of short-term rest and anti- inflammatories. The majority of adolescents will resolve as they approach maturity. Patients who fail conservative treatment, as demonstrated by return visits to urgent care, should be evaluated by an orthopaedist.

Summary

The limping child can be a daunting diagnostic problem in the urgent care setting.

Recognition of abnormal gait can be useful for narrowing the differential, as can a careful history and physical examination.

Diagnoses that can result in serious complications if missed include infections and malignancy in all age groups, toddler’s fractures in toddlers, physeal fractures in older children, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis in adolescents.

Septic joint infections need emergent surgical drainage in order to avoid irreversible cartilage damage.

Depending on the presentation, patients with malignancies may need admission or outpatient treatment, with prompt referral to a pediatric oncologist.

Fractures need to be immobilized with protected weight bearing to avoid displacement.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis requires protected weight bearing and urgent referral for surgical pinning, in order to prevent further displacement and catastrophic avascular necrosis.

References

1. Jung ST, Rowe SM, Moon ES, et al. Significance of laboratory and radiographic findings for differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:368-372.

2. Gordon JE, Huang M, Dobbs M, et al. Causes of false-negative ultrasound scans in the diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip in children.

J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:312-316.

3. Huttenlocher A, Newman TB. Evaluation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate in children presenting with limp, fever, or abdominal pain. Clin Pediatr. 1997;36:339-344.

4. Scott RJ, Christofersen MR, Robertson WW Jr, et al. Acute osteomyelitis in children: A review of 116 cases. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:649-652.

5. Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: An evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1662-1670.