Published on

Urgent Message: A quality improvement project demonstrated increased referral rates to primary care from an urgent care telemedicine service line for those who did not have a primary care provider.

Brianna Woodruff, DNP, ARNP, FNP-C; Khara’ A. Jefferson, DNP, APRN, FNP-C, CHC

Citation: Woodruff B, Jefferson K. Using Urgent-Care-Based Telemedicine to Increase Primary Care Referrals: A Quality Improvement Project. J Urgent Care Med. 2024; 18(5): 40-47.

Key words: Effective care, primary care referral, telemedicine, urgent care, access to care, shared decision-making

Abstract

Objectives: For patients presenting to an urgent care (UC) telemedicine practice, our objective was to determine if a “screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment” (SBIRT) model would increase referrals to primary care for patients who did not have a primary care provider (PCP).

Methods: This quality improvement project was conducted over 8 weeks at a UC telemedicine practice in Washington state with an average daily volume of 100 patient visits. Five advanced practice clinicians (APC) participated in this study. The SBIRT model was used as the intervention. Patients were screened for having a PCP during the visit, and those identified as not having PCP were provided a brief intervention via a shared decision-making tool on the benefits of primary care, and, if necessary, were provided a referral to primary care.

Results: Over the course of 8 weeks, 455 patients were seen by 5 different APCs in Washington state, and 95% (n = 430) were screened for having a PCP. During the intervention period, the referral rate for adult patients with no PCP increased from a baseline of 8% to 93% (81/87) over the implementation period. This exceeded the initial goal set before the project began of achieving an 84% referral rate for patients without a PCP. By the end of the implementation period, 31% (25/81) of patients already had an appointment scheduled with a PCP as a result of the referral. The intervention added an average of 2.5 minutes to each visit, which was below the set balancing measure.

Conclusion: After implementing SBIRT, the referral rate from a urgent care telemedicine service line to primary care increased from 8% to 93%, and 31% of referred patients had scheduled an appointment with primary care.

Introduction

According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services, 20-25% of adults in the United States (US) lack a primary care provider. Access to primary care has been shown to decrease overall morbidity and mortality rates and is associated with improved metrics of health equity.[1]–[2] Additionally, in 2020, the Primary Care Collaborative reported that only 8% of US adults ages 35 and older have received appropriate preventive services, suggesting that system-level efforts are needed to increase access and use of preventive care.1 US healthcare spending rose 2.7% in 2021 to reach $4.3 trillion, however, only 5-7% was used for primary care.1,[3] Annual demand for emergency and UC services is increasing by as much as 3-6% per year.[4] Studies suggest that large proportions of patients (10-60%) accessing emergency and urgent care services could be managed using lower-acuity care, such as primary care.4 Studies have shown that referring patients to primary care from the emergency department (ED) resulted in significant decreases in subsequent ED utilization.[5] Lack of access to primary care is associated with higher out-of-pocket expenses and increased emergency department use.[6]

Primary care access has also been shown to reduce overall healthcare spending, likely through chronic disease prevention and early management of health problems as they arise.[7]–[8]

Disparities in access to primary care exist, and screening patients while also assessing barriers to primary care can help mitigate these disparities.[9] Engaging patients in shared decision making (SDM) can help them make informed decisions to improve health outcomes and understanding.[10] Simplifying the referral process increases patient follow-through, and appropriate follow-up can help identify barriers.[11]–[12] The Institute of Medicine (IOM) states that strategies such as team-based care can be effective to improve access and make care more efficient.[13]

Methods

This quality improvement (QI) project was conducted at an urgent care telemedicine practice in Washington state to determine if implementing a screening and referral workflow and providing a brief intervention on the benefits of primary care using shared decision-making would increase the number of referrals placed to primary care for patients with no PCP. The practice is composed of a director of operations, 31 advanced practice clinicians, a physician medical director, registrars, and medical assistants. The clinic sees an average of 100 patients daily throughout Washington state in both rural and urban areas. Five APCs participated in the 8-week QI implementation. A random chart audit of patients was performed to make a general assessment of the proportion of patients with a PCP before implementation.

This project aimed to improve effective care in a telemedicine urgent care by increasing the referral rate to primary care for adult patients with no PCP. A goal of 84% was adopted from HealthyPeople 2030, which outlines an objective of increasing the proportion of people with a PCP to this figure by 2030.[14]

The IOM’s (2001) effectiveness framework, which emphasizes use of evidence-based care and best practices, was used to support the intervention.[15] We used the SBIRT method, which has been shown to be an effective strategy for affecting healthy behaviors and appropriate referrals.[16]

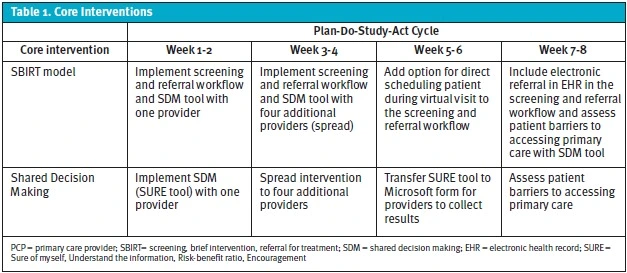

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model for quality improvement planning was used in conducting this project.[17] Over the 8-week implementation period, 4 PDSA cycles, each lasting 2 weeks, were conducted for the intervention (Table 1). Each 2-week cycle was evaluated, and 1 small test of change (TOC) was performed.

This project was given a waiver from the institutional review board (IRB) as it met federal requirements for a quality improvement project under the US Health and Human Services definition[18] and did not constitute human subjects research.

Intervention

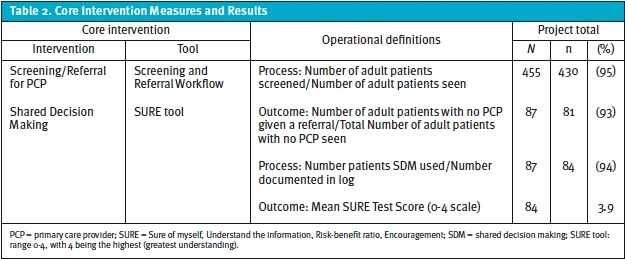

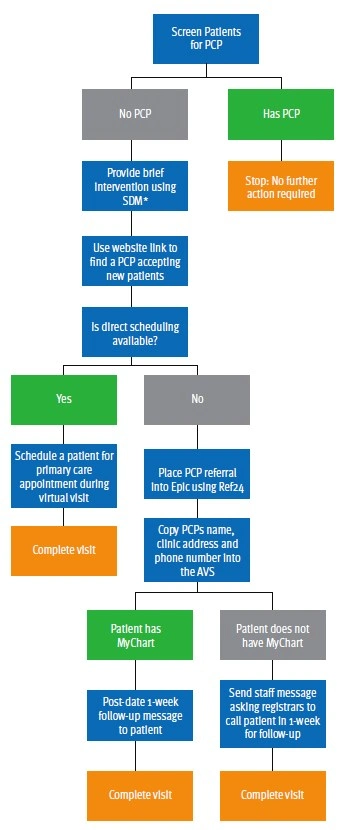

Using pre-implementation data from a causal diagram and gap analysis, several areas of improvement were identified. These included conducting screening of patients for PCPs, providing effective referrals to primary care, and providing follow-up for patients with no PCP. Using the SBIRT model, 2 tools were created to address gaps in effective care: a screening and referral workflow; and a SDM tool, which was integrated into the screening and referral workflow (Table 2). The screening and referral workflow utilized a step-by-step approach (Figure 1). First, each patient was screened by the provider to determine if they had a current PCP. If the patient did not have a PCP, a brief intervention using SDM was conducted. This involved discussing the rationale for obtaining a PCP and answering questions, then patient understanding was assessed using the 4-question SURE (Sure of myself, Understand the information, Risk-benefit ratio, Encouragement) tool using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = lowest understanding to 4 = greatest understanding).[19]

Providers then used the hospital’s website to search for PCPs who were accepting new patients. If electronic scheduling was available for the PCP, the provider would also make an appointment for the patient during the virtual visit. If no appointments were available, the PCP’s name, address, and phone number were placed in the patient’s after-visit summary. If the patient had an online portal, a follow-up message was sent to the patient 1 week later to verify they had made the PCP appointment. If the patient did not have an online portal, the provider sent a staff message to the registrars to follow up with the patient in 1 week.

Study of the Intervention

Quantitative data from each SBIRT component was collected daily. Aggregate data was interpreted at the end of each 2-week cycle for the process and outcome measure. The SURE tool was used to evaluate the patient’s decision to accept a referral to primary care. Qualitative surveys of members of the healthcare team were collected pre- and post-implementation and assessed for team member’s perspectives. Accumulated qualitative and quantitative data from each cycle were used in the TOC for the next cycle.

Measures

This QI initiative implemented 2 processes and monitored for 2 outcomes of interest. (Table 2). The process measures tracked utilization of PCP screenings and the use of the SURE tool. The outcome measures tracked referrals and the SURE tool results. Visit time was used as a balancing measure to ensure visit times did not affect the flow of the telehealth practice. We set a goal to have average visit time remain less than 20 minutes with the implementation. To ensure accuracy, tools were integrated into a Microsoft form and crosschecked with daily visits in the electronic health record (EHR). The screening and referral workflow and SDM tool were developed based on a standardized toolkit, but neither were tested for validity.

Analysis

Run charts, which display data over time, were used to analyze the data extracted from the Epic EHR. Run charts are used to determine whether a change has occurred from preintervention to postintervention.[20] Each measure (process, outcome, aim, and balancing) had a corresponding run chart. Four rules are applied to run charts to determine if results are due to random variation or due to an attributable change from the process. These special-cause signals that represent statistical significance include: runs (a group of successive points below or above the median); shifts (6 or more consecutive points on one side of the median); trends (5 or more consecutive points continually increasing or decreasing); and astronomical points (greatly different than other data).20 Each run chart was evaluated for these special-cause signals and helped to influence the next TOC. Qualitative data from field notes and team engagement were reviewed weekly for themes, and feedback was incorporated into each future TOC (iterative change).

Results

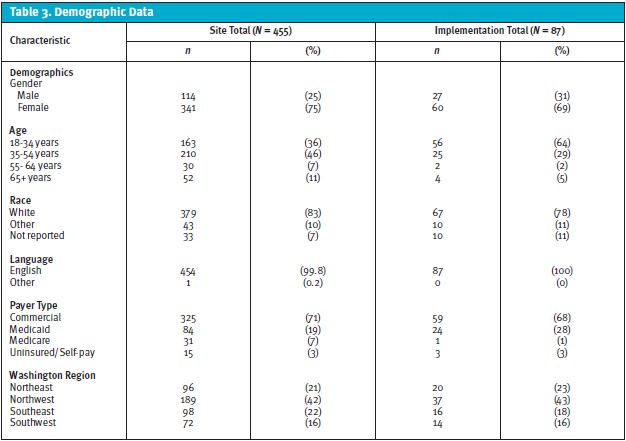

Demographics were similar between all patients seen at the site and those without a PCP. The population was primarily Caucasian, female, English-speaking, and had commercial insurance (Table 3).

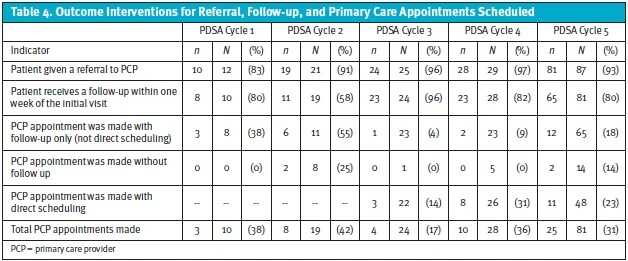

Over the 8-week implementation period, 95% (n = 430 of 455) of patients were screened to determine if they had a PCP, and of those screened, 20% (n = 87 of 430) did not have a PCP. Using SDM, 93% (n = 81 of 87) of the patients without a PCP were given a referral to primary care. Among this group, 31% (n = 25 of 81) of patients actually made a primary care appointment. (Table 4) During implementation, the average visit time increased by 2.5 minutes.

The SURE tool was used on 93% (n = 81 of 87) of patients with no PCP to ensure patients understood why they were being referred to primary care. The average score was 3.9/4 for patient understanding of the purpose of the referral.

TOC was performed for each 2-week cycle during the intervention, and there were several noteworthy findings in each cycle. As part of the workflow, the UC providers made referrals to primary care offices. Surprisingly, referral rates increased from 83% (n = 10 of 12) with 1 provider in cycle 1, to 91% (n = 19 of 21) with 5 providers in cycle 2. Providers commonly forgot to follow up with patients, and follow-up calls/online portal messages decreased from 80% (n = 8 of 10) in cycle 1, to 58% (n = 11 of 19) in cycle 2.

In cycle 3, the screening and referral workflow was adjusted to include an option, when available, to schedule patients with primary care during the virtual visit itself to improve the referral process and increase scheduled appointments. Reminders were placed in a team chat to follow up with patients to help increase the percentage of patients who received a follow-up. The reminders were an effective TOC, as 97% (n = 24 of 25) were given a referral, and 96% (n = 23 of 24) received a follow-up within 1 week—a significant increase from cycle 2.

At the end of cycle 4, barriers to primary care were assessed for themes and 4 significant themes were identified by the 28 respondents. Despite patients stating they had the tools they needed to make informed decisions, they cited long wait times to get an appointment, difficulty scheduling a visit, PCP shortages in the area, and previous PCP having retired or left the area.

Team engagement activities over the 8-week implementation focused on clear and open communication and incorporating team feedback into each TOC. The team initially rated the ease of implementation scores low, with a mean Likert score of 2.9 (1 = extremely difficult to implement to 5 = extremely easy to implement). At the end of the QI project, the team survey was repeated, and the mean ease of implementation Likert score increased to 4.3 out of 5, which indicated this project was easier to implement than anticipated. Pre- and post-surveys of members of the care team identified insufficient numbers of local PCPs and long waits for appointments as implementation barriers, which were similar to barriers identified by patients.

Discussion

Twenty percent of patients included in our project lacked a PCP, which is consistent with reported values generally in the US.2 The implementation of the intervention in this QI project increased the rate of referral to primary care of patients presenting for a telehealth UC visit within 8 weeks after initiating the SBIRT toolkit and SDM processes. Use of SDM increased to 93% over the 8-week implementation period with a mean patient SURE tool score of 3.9/4. Post-implementation team survey scores demonstrated that this project was easier to implement than anticipated, and the time to implement (2.5 minutes) remained below the balance measure goal (less than 5 minutes).

Availability and accessibility of PCPs substantially limited the effectiveness of the intervention. Commonly, patients wanted to schedule a primary care appointment during their visit, but no PCPs or appointments within PCP practices had availability. Attempts were made to mitigate access barriers by conducting follow-ups with patients who were provided with referrals. Other possible barriers that prevented successful referral included not having a dedicated referral coordinator and the lack of electronic referral capability within the EHR. The extent to which these logistical impediments affect successful referrals from UC to primary care would be a worthy topic of further study.

Implementing the SBIRT method increased screening rates, SDM, referrals, and patient follow-up. The process was intentionally kept simple in the hopes of increasing adoption by the APCs involved. Studies have suggested that making the referral process easier for patients increases the chances that they will follow through and receive care, which was corroborated by our findings.12 Prior research on this topic has shown that organizational changes in healthcare are more likely to succeed when healthcare professionals have the ability to influence the change.[21] It is likely that engaging members of the care team and integrating their feedback positively influenced rates of adoption of the changes of workflow.

Our qualitative data suggested that both participating patients and providers were comfortable with the implementation of SDM and initiating referrals for patients without PCPs as evidenced by favorable ease-of-implementation scores and dramatic increases in referral rates. Given the limited additional time added to each visit, it seems feasible that similar measures could implemented in other virtual or in-person UC visits with limited associated cost to the organization.

Despite more than 90% of patients without PCPs receiving a referral by the end of the study period, the rate of actual visit scheduling with PCPs remained modest (31%). This suggests the need for future study on the barriers preventing patients from realizing not only engagement with a PCP but actually having timely and regular access to primary care services, which are likely multifactorial.

Limitations

This project was implemented over just 8 weeks and carried out among a small group of providers in a telehealth UC practice. Considerations for implementing a process for increasing primary care referrals in other settings would likely differ. It is also possible that engagement with both patients and providers may differ due to seasonal differences in UC practice and patient volumes. Additionally, the patient population was largely privately insured, Caucasian, and English-speaking. This process may not be generalizable to UC centers serving different or more heterogenous populations. While adoption of this referral process among APCs was high at 8 weeks after initiation, it is unclear if this rate of referral placement will change at subsequent follow-up intervals.

Conclusion

This QI initiative dramatically increased the referral rate from an urgent care telemedicine service line to primary care from 8% to 93% over an 8-week implementation period. A standardized QI project design format (Plan-Do-Study-Act) was used. Periodic tests of change were used to keep clinicians engaged, and there was a high level of provider acceptance of the implementation of this process. Despite this significant increase in rates of PCP referral placement, only 31% of patients receiving a referral made a PCP appointment.

Ethics Statement

QI activities were conducted with patient and provider informed consent. This project did not secure external funding. The organization’s IRB provided a waiver of the project as it was a QI initiative rather than human subjects research.

Author Affiliations: Brianna Woodruff, DNP, ARNP, FNP-C, Frontier Nursing University. Khara’ A. Jefferson, DNP, APRN, FNP-C, CHC, Frontier Nursing University. Authors have no relevant financial relationships with any ineligible companies.

The authors acknowledge Gail Spake, Frontier Nursing University, for editorial revisions.

Manuscript submitted April 12, 2023; accepted December 15, 2023.

References

- [1] Kempski A, Greiner A. Primary care spending: High stakes, low investment. The Primary Care Collaborative. 2020:1-48. https://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/resources/PCC_Primary_Care_Spending_2020.pdf

- [2] United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Access to health services. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/access-health-services#cit3. Updated 2021.

- [3] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2021 highlights. CMS.gov https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical#:~:text=U.S.%20health%20care%20spending%20grew,For%20additional%20information%2C%20see%20below. Updated 2023.

- [4] Coster JE, Turner JK, Bradbury D, Cantrell A. Why do people choose emergency and urgent care services? A rapid review utilizing a systematic literature search and narrative synthesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(9):1137-1149. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13220. doi: 10.1111/acem.13220.

- [5] Murnik M, Randal F, Guevara M, Skipper B, Kaufman A. Web-based primary care referral program associated with reduced emergency department utilization. Fam Med. 2006;38(3):185-189.

- [6] American Academy of Family Physicians. The importance of primary care. American Academy of Family Physicians. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/advocacy/campaigns/BKG-ImportancePrimaryCare.pdf. Updated 2021.

- [7] Levine DM, Landon BE, Linder JA. Quality and experience of outpatient care in the United States for adults with or without primary care. Archives of internal medicine (1960). 2019;179(3):363-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6716. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6716.

- [8] Starfeild B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank quarterly. 2005;83(3):457-502. https://api.istex.fr/ark:/67375/WNG-9100QKHK-L/fulltext.pdf. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x.

- [9] United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Access to Primary Care. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/access-primary-care. Updated 2021

- [10] Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: A systematic review. Implementation Science : IS. 2018;13(1):98. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30045735. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z.

- [11] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ health literacy universal precautions toolkit, 2nd edition. follow up with patients: Tool #6. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool6.html#:~:text=Overview,further%20assessments%20and%20adjust%20treatments. Updated 2020.

- [12] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Health literacy universal precautions toolkit, 2nd edition: Make referrals easy: Tool #21. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool21.html. Updated 2020.

- [13] Mitchell PH, Wynia MK, Golden R, et al. Core principles & values of effective team-based health care. NAM Perspectives. 2012;2(10). doi: 10.31478/201210c.

- [14] United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Increase the proportion of people with a usual primary care provider. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/health-care-access-and-quality/increase-proportion-people-usual-primary-care-provider-ahs-07. Updated 2021

- [15] Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001. https://www.nap.edu/10027. 10.17226/10027

- [16] New Hampshire Center for Excellence. Screen & intervene: New Hampshire SBIRT. https://sbirtnh.org/process/

- [17] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) directions and examples. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html. Updated 2020.

- [18] United States Department of Health and Human Services. Quality improvement activities FAQs. Office of Human Research Participants. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/quality-improvement-activities/index.html . Updated 2021.

- [19] Légaré F, Kearing S, Clay K, et al. Are you SURE? assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Canadian family physician. 2010;56(8):e308-e314. http://www.cfp.ca/content/56/8/e308.abstract.

- [20] Ogrinc G, Headrick L, Barton A, Dolansky M, Madigosky W, (Suzie) Miltner R. Fundamentals of health care improvement : A guide to improving your patients’ care. 3rd ed. Joint Commission Resources; 2018. http://www.r2library.com/resource/title/9781635850376.

- [21]Nilsen P, Seing I, Ericsson C, Birken SA, Schildmeijer K. Characteristics of successful changes in health care organizations: An interview study with physicians, registered nurses and assistant nurses. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20(1):147. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32106847. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4999-8.

Click Here to download the article PDF.